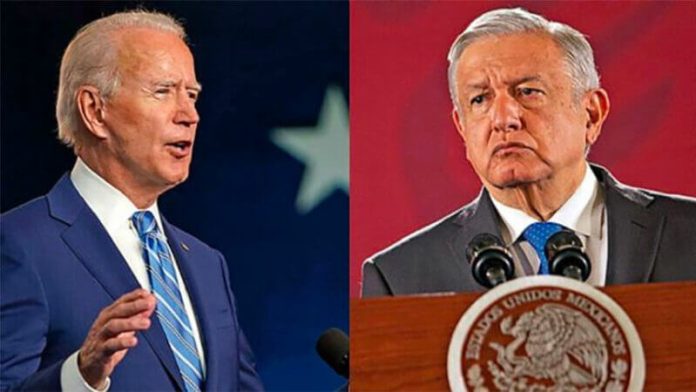

Thursday saw the relaunch of the hitherto slumbering “high-level economic dialogue” between the U.S. and Mexico, which seems to be part of Washington’s efforts to repair its ailing relationship with Mexico post-Trump.

(You’ll remember that Donald Trump tried to build a wall, slapped steep tariffs on Mexican goods and was occasionally quite rude about Mexican people more broadly).

Sounds great, but what’s a “high-level economic dialogue,” or HLED as insiders know it by, I hear you ask? It’s apparently what happens when the U.S. wheels out the secretary of state, the commerce secretary, the U.S. trade representative, the secretary of homeland security and the vice president to discuss integrated supply chains, workforce development and education, and address the root causes of immigration with Mexican officials.

The HLED, a broad diplomatic framework, first existed under the Obama administration, but fell by the wayside in 2016. It provides space for diplomats across departments to boost relations with Mexico. Under the Biden administration so far, diplomacy has focused on the various trade enforcement actions taken under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), along with efforts by Kamala Harris, the vice president, to try to get a handle on immigration, and some amount of co-operation on tackling Covid-19.

The U.S. made Mexico an (arguably late) gift of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines that can’t be used in America (because they’re not approved by its regulators).

USMCA is going well, but some, including those at Monarch Global, a consultancy headed up by a former senior commerce department official under Barack Obama, argue that more should be done to evaluate critical supply chains and to work to support them, and that more could be done, too, to figure out which industries are critical to the long-term success of North America.

“In short, we need critical thinking about an industrial policy for the region at large,” Monarch wrote in a recent note. Industrial policy, if it means subsidizing crucial industries such as those linked to green energy or those key to national security, is in vogue in Washington at the moment.

Monarch added that co-ordinated tax, investment and labor policy would help North America reshore some supply chains that are now scattered across Asia as companies have searched for lower-waged labor and, in some cases (such as the processing of rare earth minerals), weaker regulatory regimes.

But there remain difficulties between the U.S. and Mexico. On trade, Mexico’s moves to restore state control of the energy sector have gone down badly with U.S. competitors, and a dispute over the rules on car parts’ country of origin is brewing under USMCA. Immigration remains a huge point of discussion. Because Trump is no longer in office, U.S. officials tend not to refer to “bad hombres” any longer, but anxiety about immigration from Mexico — particularly in the COVID era — remains high among Democrats.

Earlier this year, Republicans sought to portray large numbers of immigrants at the southwest border as “a crisis,” and it did momentarily look like failing to get a handle on the volume of children being held in U.S. facilities could be Joe Biden’s first big fumble as president.

That problem hasn’t gone away. It’s just been pushed out of the news cycle by apocalyptic images of children falling from departing U.S. planes as America’s military completed its awkward departure from Kabul. If anything, Afghan refugees are likely to turn attacking lawmakers’ attention back to immigration, which will necessarily bring extra scrutiny of the southwest border.

So what to do? The overarching theme for sure seems to be — try to make the economies of Central America more robust. Specifically, try to make them economies in which workers are paid a living wage and have access to what Democrats view as “good things,” such as education, healthcare and transport. This is not something the U.S. can easily achieve through the mechanisms it has available to it, such as the aid budget or the Development Finance Corporation, which can issue low-cost loans and grants.

Its trade deal is clearly supposed to help too, with its mechanism for trying to improve quality of labour and workers’ rights. In fact, as Edward Alden of the Council on Foreign Relations points out, U.S. trade representative Katherine Tai often sounds more like the labor secretary than the top trade adviser.

Meanwhile, former U.S. ambassador to Mexico Earl Anthony Wayne told us that inter-agency co-operation did mean Washington could “be more serious” in its thinking about trying to lower the number of people wanting to come to the U.S. to work, or to claim asylum.

Is anything going to happen fast? Almost certainly not. As Wayne pointed out: “It’s hard to do development, economic development, anywhere in the world … but it’s better to have an institutional and regular framework to talk about it than to not.”

© 2021 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.