When Mexico steps out onto the Estadio Azteca next June, it will be the country’s 17th appearance in a World Cup tournament. This puts them 5th in a table of appearances, led by ever-present Brazil (22 tournaments), and followed by Germany, Argentina and Italy. Mexico’s success is partly a question of geography. Traditionally, North America has not been a soccer stronghold (although that is changing), and for many years, Mexico expected to represent the region in every tournament. El Tricolor has another claim to fame. On July 13, 1930, Mexico was one of four teams to play in the opening games of the very first World Cup tournament

The story of the World Cup really starts not with that 1930 tournament, but thirty years before with the Olympics. The first Olympic soccer tournament was a modest affair, staged in 1900 with just three club sides representing France, Belgium and Great Britain. The tournament slowly expanded, and while athletics generally was the star attraction of the Olympics, by the 1920s, it was the soccer tournament that was bringing in the most gate money.

Mexican football in the early 20th century

Mexican football during the 1920s centered on the Campeonato de Primera Fuerza de la Federación Mexicana de Futbol, which consisted of just nine Mexico City-based teams. It was all very amateurish, with only a couple of hundred men taking the game seriously, and the big sport clubs, with their “members only” teams, were still influential. Grounds were small, with a few hundred spectators attending the biggest games. Football was a close-knit community, and the young men who played each other on the weekend met in committees during the week, and many socialized in the clubs. The most influential of these pioneers was Rafael Garza Gutiérrez, a man who was a natural leader thanks to both his family status — they were founders of Club América — and his notable physical size. He had been Club América’s player-manager since 1917 and was still playing, although now in his thirties.

The winners of the Mexico City-based league were listed as champions of Mexico, but there were similar competitions around the country, most notably in Veracruz and Guadalajara. However, in the 1920s, it was the capital that beat at the very heart of Mexican football, and the violence of the Cristero War, which was raging across central Mexico, added to this isolation. Indeed, one of the great pioneer clubs from the countryside, Pachuca FC, had recently folded as so many of its players had fled the mining city.

The Mexico City clubs had put out a combined “Mexican” team in 1923 to play visitors from Guatemala, and there had been occasional exhibition games involving a Mexican “selection” since then. The turning point came in 1927 when Club América played Real Madrid in New York. This fed the appetite for international football and focused attention on the need to upgrade the organization from an ad hoc collection of club officials getting together to arrange the occasional game to an elected and recognized governing body. The result was the formation of the Mexican Football Federation in 1928.

The Olympics of 1928

Later that year, Mexico was one of 16 teams that gathered in Amsterdam for the Olympics. Football in Mexico was still played by amateurs, and selection for the team was as dependent on a man’s financial position as his skill on the pitch. Any players selected would have to be able to afford to take up to 6 weeks off work. As a result, the young men who sailed to Europe were either comfortably wealthy or had understanding employers. Goalkeeper Óscar Bonfiglio, for example, was an army officer and had the support of the military. Mexico’s Olympic participation lasted just 90 minutes, and they went out after losing 7-1 to Spain. However, they had planned a prolonged post-Olympic tour, travelling through Germany, Switzerland, Holland, and Belgium for the next six weeks and playing club sides such as Feyenoord, Cologne and Zurich.

It was at the FIFA Congress, staged before the Olympics, that the decision was taken to organize the first World Cup tournament. FIFA wanted to echo the financial success of the Olympic football tournament, and at the same time saw the need for a true World Championship, which, unlike the Olympics, would be open to the growing number of professional players. Several nations came forward to organise the event, but one by one they dropped out, leaving only Uruguay. The South American economy was holding up well, there was immense pride in their football team, which had won the last two Olympic titles, and 1930 would see the country celebrate 100 years of independence. It seemed perfect timing, and plans were immediately laid down to build a gigantic concert stadium to host the event.

The first World Cup

There would of course be problems. Passage would be by sea, meaning players would be away for at least six weeks. This would not clash with the European season, but it would take players away from their families and interrupt the traditional summer rest period. The February deadline for entering came and went with no European sides committed. Political pressure was applied, and France, Belgium, Romania and Yugoslavia agreed to send teams, but the target of sixteen sides was not reached. In addition, Egypt had entered but was delayed by a storm in the Mediterranean and literary “missed the boat” that was to bring them on to South America.

When the World Cup invitation had first been received in Mexico, Juan José Luqué de Serrallonga had been invited to coach the team. He was a Spaniard who had moved to Mexico in 1928. Back in Spain, he had played for his local side Cádiz CF, where he had been a useful goalkeeper, and he was now coaching in the Mexico City league. On May 25, 1930, Serrallonga invited the best players in Mexico City to play an exhibition game to help select the World Cup team. Of the 17 players selected for the squad, five were from Club América and seven from Atlante. Five of the 1928 Olympic team retained their place, and there were also two sets of brothers, Manuel and Felipe Rosas and Francisco and Rafael Gutiérrez. Then, as now, fans and the press had their own strong ideas.

The appointment of Luque de Serrallonga was particularly criticized. There was a belief that the position should have gone to a Mexican, while El Universal suggested that, after average performances coaching Real España and Germania, he ”lacked the merits” to hold such a position. A thoughtful journalist at El Universal questioned the policy of limiting selection to players from Mexico City, and fans at the final warmup games called out the names of players they wanted added to the squad, most notably América’s Luis Cerrilla.

The journey to Uruguay

The team had to take a roundabout route to Uruguay, first travelling to New York, where, on the evening of June 13, they and the US team boarded the S.S. Munargo. It was an 18-day trip to Montevideo with stops in Bermuda and Brazil, and training on board was difficult, “an open deck for exercising,” and “very poor bathrooms,” as the US team explained to the press.

Mexico had been drawn in Group 1, the only group to have 4 teams, and they would be facing Argentina, one of the favourites for the trophy. Workmen were still rushing to finish the Estadio Centenario, so on July 13, Mexico and France faced each other in the modest Estadio Pocitos. Playing in dark maroon shirts, Mexico showed naivety in defence, crowding their penalty area without tightly marking the opposing forwards. In the 19th minute, the ball came in from the right, and there was Lucien Laurent, standing unmarked, to score the first-ever goal in the World Cup. In the 26th minute, the French goalkeeper fell to the feet of Mejia and had to go off injured. Down to ten men, and with a defender now in goal, France still raced to a comfortable 3-0 halftime lead. In the 70th minute, Juan Carreño, who had scored Mexico’s first goal in the Olympics, scored their first goal in the World Cup, but France ran out 4-1 winners. Mexico’s second game was against Chile, and once again, Mexico lost. The final score was 0-3 with Manuel Rosa unlucky to have the ball hit him and bounce into the net for the first own goal of the tournament.

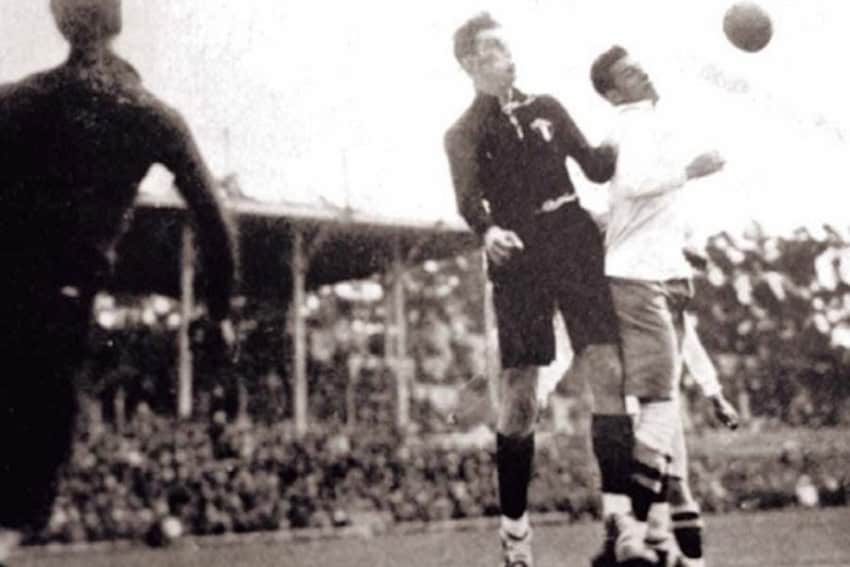

Mexico game in a losing effort against Argentina

On July 19, Mexico played its third match in a very different atmosphere. The new stadium was ready and the heaving bowl was packed with 42,000 fans, the majority having caught the ferry from Buenos Aires to support Argentina. Argentina were 3-0 up after 17 minutes, and Bonfiglio in the Mexican goal had saved a penalty. That incident became a football legend. There are accounts that Fernando Paternoster, disagreeing with the referee’s decision to award the kick, had deliberately hit the ball into the goalkeeper’s arms, or that the penalty spot had not been marked on the pitch, and the inexperienced referee had paced out too many steps. Just before half-time, Mexico also won a penalty. Manuel Rosa, he of the earlier own goal, stepped forward to hit it into the net. Rosa was only 18 years old and would hold the record as the youngest goalscorer in the FIFA World Cup until Pelé arrived on the scene 28 years later.

The goals continued: 4-1, then 5-1, before Mexico was awarded a second penalty, the third of the game. This time, goalkeeper Ángel Bossio got a hand to the ball, but it fell back to Rosa, who scored his second goal. When Roberto Gayón made it 5-3, it looked for a moment as if Mexico might actually perform a football miracle. But Argentina put the game beyond reach with their sixth goal. Mexico would come home without taking a point from their three games. Even so, they had come out of the tournament with honor, particularly in this last game. “Mexico Plays Well in Montevideo,” was the headline in El Universal.

The players of 1930 have long ago slipped out of the public spotlight. Dionisio Mejía later became the key striker in the team, scoring 7 goals in the 1934 qualifying campaign. Alfredo Sánchez was still playing for Mexico at the 1938 Central American and Caribbean Games, and Juan Carreño, the scorer of Mexico’s first goals in both Olympics and World Cup, was the league’s joint top scorer when Atlante won the title in 1932. He died of appendicitis aged just 31. Goalkeeper Óscar Bonfiglio went on to have a distinguished army career, and Rafael Garza Gutiérrez continued to be involved with Club América for another twenty years. The boys of 1930 made up a unique group of colleagues and friends. They would be the last Mexicans to play in the World Cup until 1950.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life-term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.