Rocky Contos is the Director of SierraRios, a nonprofit organization that offers rafting trips down big, Grand-Canyon type rivers around the world; these include rivers in Canada, South America, China, Africa and Mexico.

“My goal,” says Contos, “is to bring people to these rivers so they will appreciate their beauty and to raise their awareness so they will work to protect them.”

“Of all these river trips you’re offering,” I asked Contos recently, “which one would you recommend for complete beginners?”

“In my opinion,” he replied, “the best first river for anyone to do is the Usumacinta, which is the biggest, most voluminous river in all Mexico and Central America and forms part of the border with Guatemala.

“You’re on the water six days. You get the experience of camping; you get to run some rapids, but nothing too difficult or scary; and you get a marvelous experience because you’re floating through the rainforest, and the jungle is just incredible.

“It’s a corridor with the highest concentration of howler monkeys in the world — those were the sacred monkeys of the Mayan people — and you get to camp at two outstanding Mayan sites: Yaxchilán in Mexico and Piedras Negras on the Guatemalan side; so the trip has a lot of cool things about it.”

In early February of 2023, nine would-be rafters from Mexico, France, Canada and the United States participated in a SierraRios trip down the Usumacinta River in the care of an international crew of six guides.

Members of the expedition met at the Hotel Chablis near the celebrated Maya ruins of Palenque, where Contos gave them the instructions for their adventure. The following morning, they visited Bonampak, famous for its colorful floor-to-ceiling murals painted around A.D. 700.

From there, they went to the border town of Frontera Corozal, where they packed all their gear into watertight bags and set off down the river on February 5 on five rafts, two kayaks and an inflatable paddleboard.

“After three hours,” says Canadian Chris Lloyd, “we arrived at Yaxchilán, which has the best preserved carvings in the Mayan world, and found we had the whole place all to ourselves. There’s an old air strip there, and we camped right on the edge of it, which is also the edge of the ruins.

“Here, we got a big welcome from the howler monkeys, who appeared just as soon as we set up camp and made it very clear to us that this was their neck of the jungle and that they were in charge, not us. In case you have never heard a howler monkey… , they are really loud and they sound pretty much like a lion roaring 10 meters above your tent.”

“Yaxchilán is truly a jewel,” recalls Mexican participant Maruca González. “You feel at peace, and it has beautiful energy. There are three different routes for visiting the ruins and we did all of them, returning to the camp in the evening, where our guides had prepared dinner.”

“For an appetizer,” says Lloyd, “we had a plate of cheese and crackers plus dips and nice pesto sauce. This was followed by a main course, some of the best tamales I’ve ever had in this country. Big ones they were, wrapped in banana leaves, and they were filled with delicious chicken and vegetables.

“On another occasion… they actually made two lasagnas: one with meat and one without. Then you might get brownies made in a Dutch oven for dessert. There was always lots of wine and cold beer, and we also had drinks like vampiros and piñas coladas.”

Early the following morning, Lloyd received special permission to climb up to a high point where he was able to watch the sun rise over Yaxchilán. “This was in an effort to spot owls at this place, but of course it gave me an opportunity to really appreciate these extraordinary ruins.”

The following day the group covered some 50 kilometers on the river to reach the ruins of Piedras Negras.

“The Usumacinta is a very impressive and very wide river,” Lloyd told me. “The waves weren’t very big, but the currents were really strong, with whirlpools all over the place. They would grab your raft, spin you in a circle and spit you out, but there was never any danger of the rafts flipping over. It was never more than a Class 2 river, which is pretty moderate.”

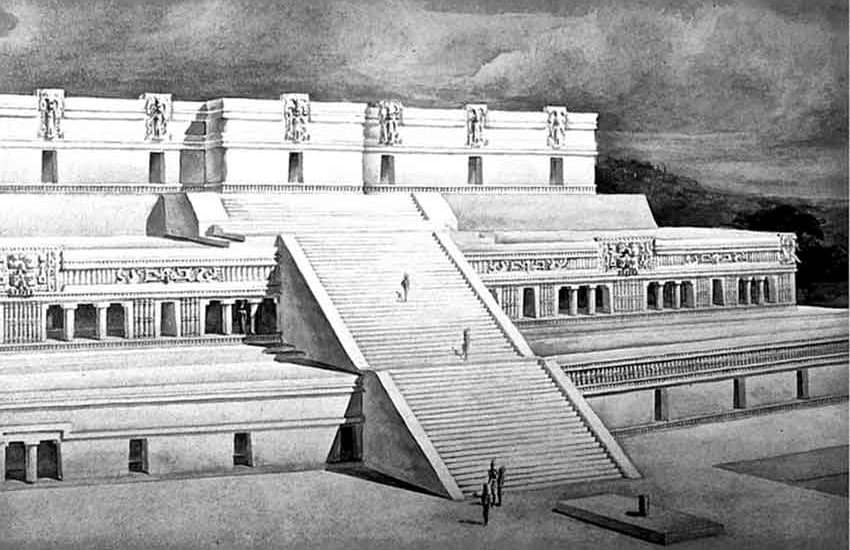

Piedras Negras is part of Guatemala’s Sierra del Lacandón National Park and is known for its abundance of sculptures. It can only be reached via the Usumacinta or by air.

What put Piedras Negras on the map was a Russian-American archaeologist named Tatiana Proskouriakoff who figured out how to decipher the Mayan hieroglyphs there.

In 1978, she died and, after waiting more than a decade for political tensions to ease along the Usumacinta, her colleague David Stuart carried Tatiana’s ashes to Piedras Negras, where they were interred at the summit of the Acropolis, where her career had been launched.

In spite of all this, little restoration work has been done at the site, and those who arrive there by raft have the place to themselves.

“We are the only tourists here,” wrote Maruca González in her journal. “The Guatemalan government has no funds for restoration, but I think that makes me like the place all the more. The rocks are covered with plants and mushrooms, with spider monkeys scrambling in the trees. Most of all, I liked the ancient Temazcal (sweat lodge). There was room for all of us inside.”

Further downstream, the group enjoyed swimming in crystal-clear waterfalls and lagoons alongside the river, running four rapids and speeding through a narrow canyon with sheer walls a kilometer high.

The expedition ended at Boca del Cerro, Tabasco, on February 10. “Did you like the experience?” I asked González.

“Did I like it? I guess so,” she replied with a big smile, “because I’ve already made plans to go back there next month to spend more time at those two incredible ruins on the Usumacinta. I think I’ve fallen in love with the place!”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.