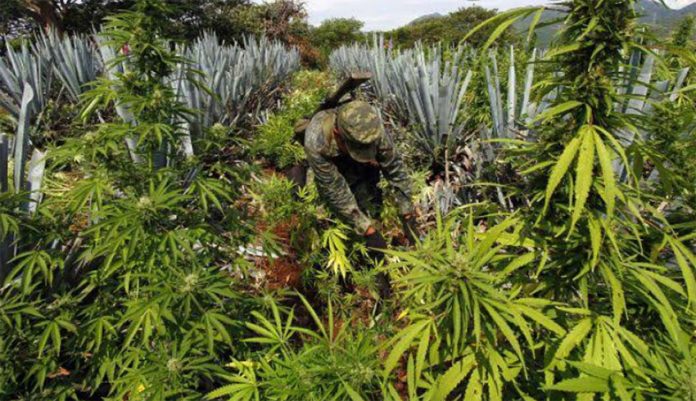

As Mexico nears full legalization of marijuana, some illegal growers are worried about what will happen to their livelihoods. With legislation awaiting final Senate approval for recreational use and sale, some growers have already seen their sales shrink, according to a report by the Associated Press.

For María, a marijuana grower near Badiraguato, Sinaloa, that means half her crop is sitting in storage when it should have already been sold. She attributes the change to the pending legalization, which has shaken up the illegal market. Demand had already been falling as many U.S. states legalized marijuana and drug cartels added fentanyl and other more profitable synthetic drugs to their portfolios.

For María and her family, marijuana pays for everything except the food they grow for themselves. Clothing and her children’s education have all been financed by the crop. But the years of plenty were accompanied by periods of violence, when rival groups sought to control the area.

Some growers are diversifying into opium poppies to balance the risk that their marijuana crops will not sell in the new business ecosystem created by legalization. That is the strategy that María and her family took.

“Since we heard they were going to legalize [marijuana] we began to make the poppy plots larger,” María said. But their efforts to grow opium were stymied by a government operation that sprayed herbicide over her fields.

The next strategy was to grow a high-quality strain. The family hopes it will be easier to sell.

The marijuana they sold from the previous harvest yielded US $500, or about $25 per kilogram. The destroyed poppies would have netted the family about $5,000.

Another man in the area, who requested anonymity to speak freely, said he also grows a strain with higher psychoactive content that normally sells at 10 times the price of standard Mexican marijuana. Two harvests normally yield $15,000, he said. But it is not easy money. He has to fight for water and pay a fee to dealers in order to sell in their territory in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa.

Both he and María were less concerned about legalization than sales.

“If they pay me the same — or almost — being legal, well great. We’ll work more at ease,” he said.

Mexican politicians commonly cite reduced violence as a motivation for legalization.

Zara Snapp is an international drug policy consultant and co-founder of Instituto RIA, a public policy think tank in Mexico. She said that violence will not be reduced overnight, and the legislation needs a strong social justice component.

The objective “is not to end the illegal market, because that’s not going to happen in the first years,” but rather reduce it as much as possible, said Snapp. “If the communities decide not to [move to the legal market] it is because there aren’t sufficient economic reasons.”

Source: AP