During an intimate moment in her studio, the legendary Mexican artist Frida Kahlo shares her thoughts on color with her lover and fellow artist, Spanish Civil War refugee Josep Bartoli.

After he confesses that he is afraid of using color in his work, she reminds him, “Color is everywhere.” To reflect this, she paints three strokes across his jaw to indicate the three subtle color variations of a flower’s shadow.

This scene from the new French animated feature film Josep reflects Bartoli’s reluctance to bring brightness into his art before coming to Mexico.

The late artist — a Catalan who fought for the Spanish Republicans during the civil war before being interned in the infamous Rivesaltes camp in southern France — escaped to Mexico after the Fall of France in 1940.

In Mexico, he sought to make the world aware of the horrors he had suffered in internment as well as to create a new life for himself.

Directed by acclaimed French cartoonist Aurel, Josep was most recently spotlighted at the Miami Jewish Film Festival last month.

“[Bartoli] began using color in his drawings after he was in Mexico,” Aurel wrote in an interview by email. “Before, he was only known through his black-and-white ink drawings. In Mexico, he traveled and drew a lot. And in his sketchbooks, little by little, you saw he began to experiment with some colors in his line drawings.

“We therefore decided to pursue this idea … Color came to him thanks to Mexico, and thanks to Frida.”

Kahlo and Bartoli exchanged real-life love letters — her correspondence with him was auctioned off in New York in 2015 — although Aurel says that it is hard to know exactly what their relationship was. The film depicts their romance taking place during Kahlo’s stormy marriage to Diego Rivera, while Bartoli seeks news of his missing fiancée María, who was pregnant when she disappeared.

Josep represents a 10-year odyssey for Aurel. He had to balance working on the film with his day job — drawing for the French daily Le Monde.

The film has met with significant acclaim, from a screening at the Cannes film festival last year to a nomination for a French César award, the nation’s equivalent to the Academy Awards, for best animated film.

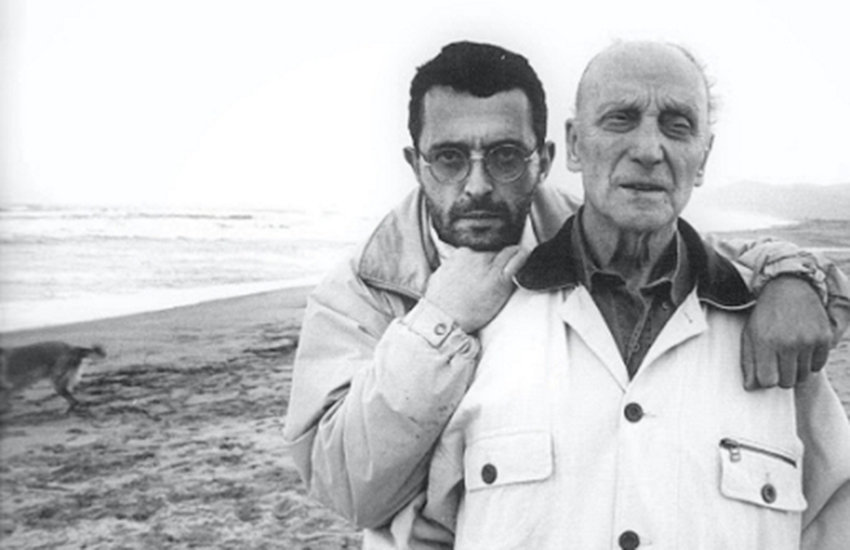

Not only did Aurel direct the film, he also drew artwork for it, including representations of its title character and Kahlo. Aurel chose different aspects of each character to highlight, from Bartoli’s five o’clock shadow to Kahlo’s dangling cigarette and earrings.

The film is told in a unique way, from the perspective of a fictional character named Serge. A former guard at the Rivesaltes camp, the film begins decades later in Marseilles, when now-elderly Serge is receiving a visit from his teenage grandson Valentin.

When Valentin discovers a mysterious artwork on his grandfather’s wall, it prompts a journey through memory into a grim period of history — La Retirada, (the retreat), i.e., the mass exodus of Republican refugees from Spain into France in 1939, following Francisco Franco’s victory in Spain’s civil war.

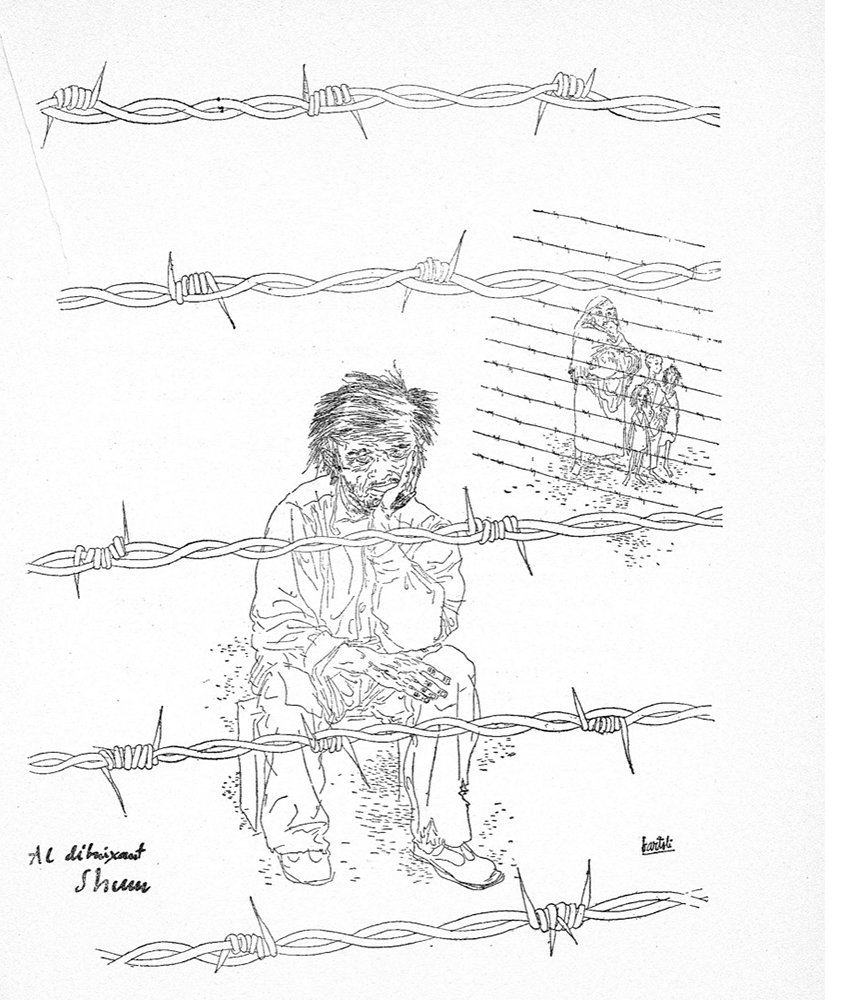

Bartoli and fellow refugees were interned at Rivesaltes and other camps. The film shows them suffering from sadistic guards, including a commandant eventually depicted as a pig. The film notes that these camps were established in early 1939, before France declared war on Nazi Germany.

Serge grows disgusted with the cruelty of his fellow guards and befriends Bartoli. Hope is hard to find for the imprisoned artist: he is waiting for María; the guards desecrate his artwork; he cannot escape the barbed-wire-covered surroundings. All he can do is sketch and wait.

In one scene, an imaginary Kahlo emerges from the sea to inspire him with words from one of her actual letters:

“Josep, tonight I felt wings caressing me from all over. It was like your fingertips had mouths that kissed my skin.”

Aurel credits his discovery of Bartoli to a 2009 book by the artist’s nephew, Georges Bartoli, called La Retirada, about the flight of the Spanish Republicans. The book is illustrated with his uncle’s artwork.

Aurel credits both the artist’s widow, Bernice Bromberg, and his nephew with facilitating research.

“I love seeing the film,” Georges Bartoli said in a Zoom interview, including “the music and the artwork.”

“My uncle’s years in Mexico are less well-known,” Bartoli said, adding that he did not know many details about his uncle’s relationship with Kahlo. “My uncle never spoke about this subject with us,” he said.

In the film, Josep Bartoli goes to Mexico after Serge helps him escape from captivity. Eventually, Serge — who by this time has joined the Resistance — decides to visit his friend in Mexico.

After docking in Veracruz and taking a bus inland with passengers, including a mariachi band and a rooster, Serge arrives in Mexico City. Bartoli introduces him to Kahlo, who gives him a salty reception.

They visit not only Kahlo’s studio but also the house where Leon Trotsky was assassinated in 1940. Bartoli marvels that if he had not been fighting for the Spanish Republic, he might have been one of those enlisted in the plot against Trotsky.

In Mexico, Bartoli made intricate drawings of cathedrals and worked to make the notorious French concentration camps known worldwide through a 1944 book of drawings, Campos de Concentración 1939-194… Georges Bartoli has an inscribed copy, which he brought out during the interview.

“More than anything, [Mexico was] a country in that era [that was] very open and welcoming to the Spanish Republicans,” said Georges, a documentary photographer who has himself traveled to Mexico to chronicle the Zapatistas and Subcomandante Marcos.

Ultimately, in the late 1940s, Bartoli left Kahlo and Mexico for the United States, where he returned to painting and formed friendships with prominent artists such as Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning. He contributed artwork to Holiday magazine, which made him among the highest-paid illustrators in the U.S., according to his nephew.

He kept his Mexican citizenship and went back at various moments — including in the early 1950s, when he met his first wife, artist Michelle Stuart, at the Galería Prisse on Londres Street, near the Hotel Geneve.

Stuart remembered “the whole atmosphere around the gallery openings and exhibits” in the Mexico City of the era.

“It was very lively,” she said. “There were not many art galleries. There were a few galleries but, of course, some wonderful artists.”

Of Bartoli’s prior relationship with Kahlo, Stuart said, “I think they were lovers quite a few years … Everybody knew about it. They auctioned off her letters in New York, millions of letters. You don’t write letters to people unless you’ve got a strong bond with them. He had a whole trunkful of memorabilia from his relationship with Frida. He was very quiet about it.”

“He kept a very low profile,” she added. “He was not a fanfarrón [braggart]. He was very quiet, thoughtful, intelligent, an extremely interesting artist.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.