The Mexican jazz community is in mourning after one of its most preeminent members passed away in Mexico City last Thursday.

Fortino Contreras González, a composer, pianist, drummer, trumpeter and vocalist known as Mexico’s father of modern jazz, died of a heart attack at home, his manager, Mónica Ramírez, told the Associated Press. He was 97.

“One of the greats is gone: Tino Contreras, a legend of jazz in Mexico who infected many generations of artists with joy and inspiration,” Culture Minister Alejandra Frausto wrote on Twitter. “With his creations, he played the notes of the world. With his music, he explained life itself.”

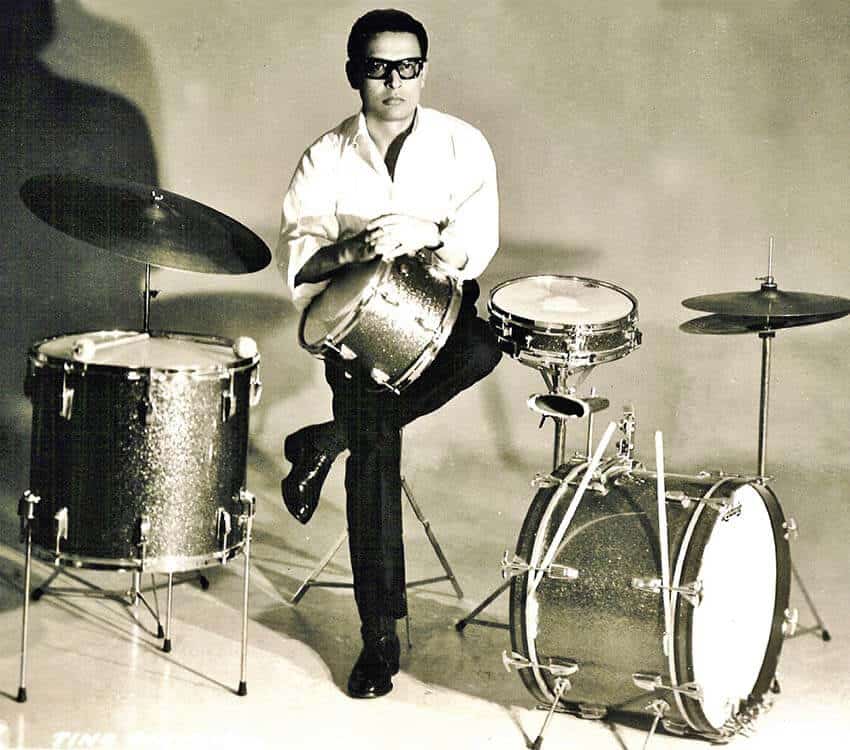

Born in Chihuahua city in 1924, Contreras moved to Ciudad Juárez at a young age and put together his first band – Los Cadetes del Swing – in the northern border city, located on the doorstep of a dynamic jazz scene in the United States. His younger brother, Efrén, a talented saxophonist, was one of the group’s members.

In the 1950s, Contreras moved to Mexico City and proceeded to “change the rules of the [jazz] game,” according to the newspaper El País.

“Modern jazz arrived with him,” said Carlos Icaza, a musician who collaborated with Contreras during the final 20 years of his life.

“[Jazz musicians] played with sheet music before that, but Tino told them that you have to feel jazz because he brought with him everything that was happening on the border,” he said.

Midway through the ’50s, Contreras founded the capital’s first jazz club, El Rigus, and began recording his own compositions.

In a long and prolific career, Contreras would go on to record more than 50 albums with scores of different musicians. He toured extensively around the world, sharing stages with such luminaries as pianist Dave Brubeck and saxophonist Cannonball Adderley. He also collaborated with legendary Mexican actor Germán Valdés, or Tin Tan, writing music for some of his films.

His best-known recorded work is perhaps Misa en Jazz, released in 1966, one of 59 albums he released.

While his music remained within the realm of modern jazz in Mexico, he wasn’t afraid to borrow elements of other genres to spice up his compositions and even experimented with pre-Hispanic Mexican instruments.

Yumaré, a 1980s album, featured percussion instruments from the Tarahumara region of his native state.

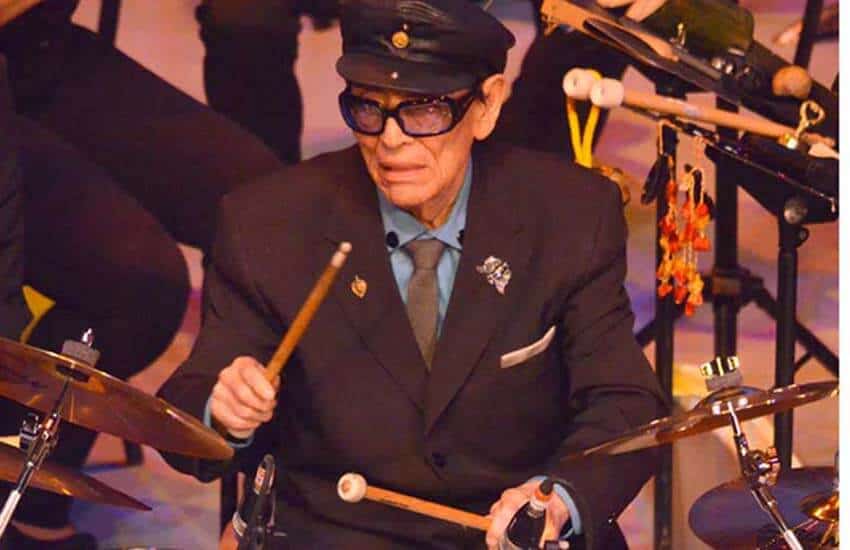

Contreras, the recipient of numerous awards, kept composing and performing right up until his death, always decked out in his trademark cap and shades.

In April this year he performed a set from the Casa Azul, the Frida Kahlo museum in Mexico City, that was streamed online to a global audience.

“Jazz music always moves not with time but ahead of time,” he told the Associated Press before the concert. “It leaves an impression. That’s what we’re leaving.”