A leading medical journal has published a damning indictment of Mexico’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, claiming there was a breakdown in the effective functioning of the health system due to the federal government’s deflection of responsibility for “essential decisions that require centralized stewardship.”

Researchers presented a new concept – “punt politics” – in a paper published by The Lancet about what they described as the failure of health system stewardship in Mexico and Brazil during the pandemic.

“Punt politics refers to national leaders in federal systems deferring or deflecting responsibility for health systems decision-making to sub-national entities without evidence or coordination,” the paper said.

“The fragmentation of authority and overlapping functions in federal, decentralized political systems make them more susceptible to coordination problems than centralized, unitary systems. … Punt politics has been the operating principle for COVID-19 in several countries around the world, particularly where federalism coincides with populism.”

The paper notes that the Mexican government declared a national health emergency on March 30, 2020 – a month after the first case was detected – “but punted responsibility to the states to determine what constituted timely action.”

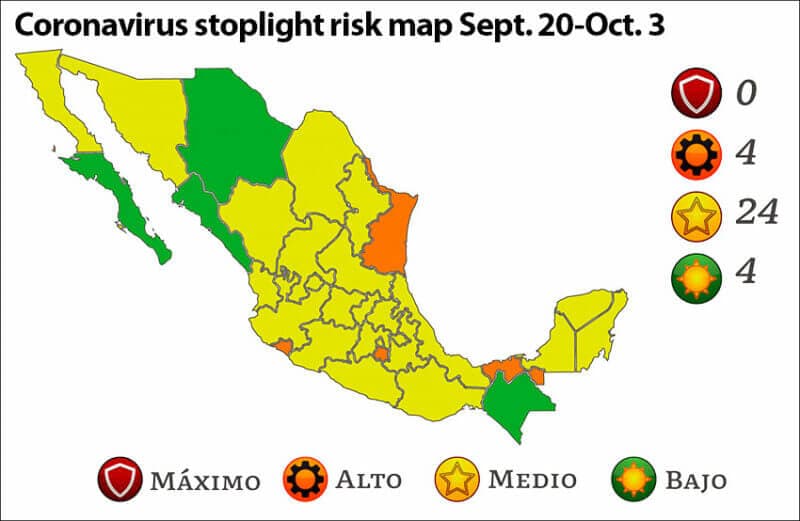

That deflection of responsibility is perhaps best demonstrated by the federal government’s introduction in June 2020 of a stoplight risk alert system, which provides advice about when restrictions should be tightened and eased but ultimately gives states the freedom to decide how to go about combating the spread of the coronavirus.

Before that, on April 21, 2020, the Ministry of Health gave state governments the responsibility to implement the necessary public policies to promote physical distancing and prevent transmission of the virus, the researchers said.

In both Mexico and Brazil, “the absence of national stewardship fostered a fragmented NPI [non-pharmaceutical intervention] response across state and municipal governments, lacking an evidence base,” the paper said.

It acknowledges that some states and municipalities implemented COVID mitigation policies ahead of national governments but others limited themselves to following federal guidelines, “thus reacting slowly and incompletely.”

In Mexico, the federal government never ordered a strict lockdown and didn’t advocate forcefully for the use of face masks, especially early in the pandemic.

Instead, “President López Obrador promoted the benefits of a lucky four-leaf clover that ‘protected’ him from the virus,” The Lancet paper said.

“He also downplayed the COVID-19 threat in the initial stages of the emergency, encouraging the population to continue their daily activities and interactions, such as going out to eat in restaurants, traveling, and attending rallies into late March of 2020,” it added.

“… Lockdowns were late and partial, and testing, contact tracing, quarantines, and isolation programs have been minimal, while vaccine rollout has been slow,” it said, referring to both Mexico and Brazil, which respectively rank fourth and second in the world for COVID-19 deaths.

The researchers argued that the punt politics approach didn’t work because it wasn’t supported by adequate “real-time testing data that trace the spread of the infection and viral genomic sequencing for identifying the spread of new variants.”

“… Sub-national policymaking must then rely on mortality data which lag by weeks at best. During a pandemic, policymaking that is guided by mortality data is necessarily slow, reactive, and ineffective, compared to policymaking based on wide scale, equitably distributed testing accompanied by accurate diagnosis,” the paper said, noting that in late August Mexico ranked 168th out of 209 countries for its per-capita testing rate.

With regard to the different ways in which states in both Mexico and Brazil responded to the pandemic, the researchers said the political leanings of state governors might explain some of the variation observed, providing evidence of a partisan pandemic.

“In Brazil, allegiance with, or opposition to President Bolsonaro is strongly correlated with state policy decisions, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. Governors on the rhetorical left and center initially implemented more stringent NPIs,” the paper said.

(Ten non-pharmaceutical interventions were considered: information campaigns, international travel limits, travel limits within states, meeting/gathering size limits, public event restrictions, workplace closures, school closures, suspension of local public transport, stay-at-home orders and mask-use mandates.)

“Political alignment with the president explains less of the variation across Mexican states relative to Brazil, suggesting a policy vacuum,” the paper said.

“More stringent responses did not come exclusively from opposition governors. Yet, opposition governors were among the first to act and contrast themselves with the national government, and none of the best performing states’ governors are aligned with López Obrador. For example, centrist and right governors (opposition) were particularly stringent in mask mandates relative to those on the left.”

The paper says that Chiapas – under Morena party Governor Rutilio Escandón, an ally of López Obrador – “stands out as having several low NPI scores throughout the pandemic” – although paradoxically it has the lowest case tally and second lowest death toll among Mexico’s 32 states.

“In Mexico, [information] campaigns were strong and consistent across most states, with a few notable exceptions, such as Chiapas,” the paper said.

“Mask use mandates are consistent and relatively rigorous in many Mexican states, but several states implemented them late. Chiapas never went beyond recommending mask use.”

The researchers also noted that national responsibility for managing the pandemic in Mexico was not concentrated with the president but rather the office of Deputy Health Minister Hugo López-Gatell.

The paper noted that along with the president, [López-Gatell also downplayed the gravity of the threat and made “not overreacting a guiding principle, creating obstacles for a strong and coordinated national response,” the paper said.

In their conclusion, the researchers – among whom are former Mexican health minister Julio Frenk and his wife Felicia Knaul – asserted that “populist regimes are attracted to punt politics because their objective is political gain, not maximizing health outcomes.”

“A defining characteristic of populist regimes is valuing and prioritizing power as an end goal rather than a means and, in the case of a pandemic, this implies that policy adoption (or lack thereof) will not be based on prioritizing health needs, promoting trust, or eliciting population compliance,” it said.

“… Instead of harnessing and applying evidence and science in a coordinated manner, Mexico and Brazil’s leaders employed punt politics to achieve political gain or avoid the political cost of implementing unpopular policies such as lockdowns. The result is a health system where some components are functioning, while others, like disease surveillance, are not; the lack of coordination leads to a whole that is far less than the sum of its parts.”

Mexico News Daily