Girls come to Mazatlán’s Casa del Mar for a variety of reasons — from broken homes affected by drug addiction, violence or severe poverty.

This 94-year-old girls’ home functioned as an orphanage when it originally opened in 1927 after the Spanish flu swept the city and left multitudes of children without families. But these days, the societal problems that bring the girls here have changed, and three years ago, so did Casa del Mar’s focus.

“As a system, we’ve shifted to a human rights focus,” explained Gabriela Ramírez Landeros, president of the institution’s board of trustees. “We don’t want pity — it’s our duty as a society to take care of these children. We want to give them the ability to have an independent future, employability and [the ability] to choose a career and train in that field.”

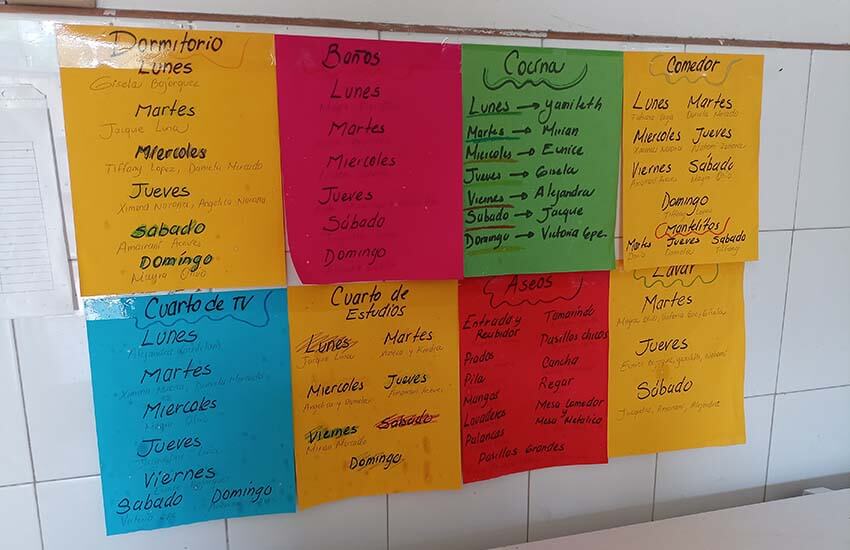

The changes are obvious in almost every aspect of the program and the girls’ lives: they’re expected to contribute to their “community” in big and little ways and share in making many of the decisions that affect their lives. The new name, Casa del Mar, was voted on by the girls two years ago to avoid the stigma of the word “orphanage,” although the nonprofit is still registered as Orfanatorio de Mazatlán and donations are still tax-deductible.

“It’s very important to us that they can make their own decisions,” explained Ramírez. “Part of living in a community is that you have to contribute. This is about their lives, not just our authority.”

Before, birthday cakes were purchased; now the cumpleañera’s friends make it. In the past, a staffer would sort donated clothing and decide what garments went to which girls and which items needed to be purchased new.

“Now the girls have a say in what they wear; they have a voice,” said Ramírez. “If they choose to wear their fancy dress on a Monday, that’s OK!”

The girls have regular chores and duties that change monthly. They can earn money by taking on extra tasks, and the girls learn to set goals and save for them.

Casa del Mar’s imposing property covers almost an entire block with high walls surrounding multiple courtyards, a huge playground and the main building, which encircles a big central courtyard with bicycles lined up neatly on one side.

A long, dormitory-style bedroom houses the younger girls in neat rows, while teens have their own room. The spacious remodeled bathroom features modern individual shower stalls. Each girl has their own closet/locker for clothes and personal items, as well as a nightstand next to their bed.

Other areas include a playroom with a big TV and lots of toys, a study/sewing room and a computer room where the girls can do schoolwork. Posters about self-esteem dot the walls, as do paintings done by the girls. A spotless stainless-steel kitchen and dining room are decorated with more of the girls’ artwork, these ones about healthy eating and good nutrition.

Twenty girls, aged five to 19, currently live at Casa del Mar. Some were referred by the DIF family services agency, but nowadays they’re more often brought to the program by family members looking for assistance with their care.

For example, a girl may be living with a grandparent who has to work and can’t care for her during the week. Working within the parameters of a special program, she can live at Casa del Mar from Monday to Friday and go home on weekends.

“Most of them, all of them, come from broken homes or where parents have abandoned them,” explained director Rafaela Cornejo Valdovinos, who has worked at Casa del Mar for almost 20 years.

“Parents must understand that we are not the enemy,” added Ramírez. “We’re not judging, we’re helping.”

Can parents visit?

“We have to see that the girls are safe,” said Ramírez. “Some parents are allowed to visit; some don’t want to. That’s really hard to explain to the girls.”

One might assume there’s funding from the city to help defray costs, but Casa del Mar only receives 2,000 pesos a month from Mazatlán’s municipal government. Sponsors include big companies like Lala, which donates milk products, as well as volunteers who take the girls on outings, teach them to sew or read to them for story hour.

“We have lots of volunteers in the health field: doctors, dentists, therapists and nutritionists,” said Ramírez. But, she added, “Money is always the best donation.”

Casa del Mar carefully screens volunteers with in-person interviews that include questions about the applicants’ families and backgrounds.

“It has to be something to benefit the girls,” explained Cornejo. “We ask them to present their idea and objectives. There are rules and regulations they must agree to, and we work together to oversee what they’re doing and how the girls feel about it.”

The girls are offered therapy, which is suggested but not forced. The girls must decide if they’re able and want to move forward in order to cope with their past neglect and abuse.

“It’s not mandatory,” said Ramírez. “But we encourage them because it’s the only way for them to help themselves.”

When girls “age out” of Casa del Mar they don’t have to leave if they’re willing to continue their studies. It costs 3,000 pesos for a month of school-related costs, paid for by sponsors.

Since the pandemic shut down in-person school, Casa del Mar has contracted two teachers to visit three hours a day at a cost of 200,000 pesos for the year. (High schoolers have virtual classes.)

Since its inception, 2,500 girls have lived at the facility.

“Hopefully, this will be the first generation of girls to go on to university!” said Ramírez.

• Interested in volunteering? Find out more on the Casa del Mar website or send an email with details about what you’d like to do. Reach them by phone at (+52) 669-981-2214.

Janet Blaser is the author of the best-selling book, Why We Left: An Anthology of American Women Expats, featured on CNBC and MarketWatch. She has lived in Mexico since 2006. You can find her on Facebook.