Santos Popoca Fernández and I were standing at the edge of a small orchard outside of San Pedro Yancuitlalpan, Puebla, when he pointed into the distance.

“That is Teotón,” he said.

I nodded, unsure why he bothered to point it out. It looked like a fairly unimpressive hill.

“It is not a hill, it is Teotón,” he said. “It is a pyramid.”

“A pyramid?”

“Yes,” he replied. “It is larger than the pyramid in Cholula.”

I stared at it for a while, trying to wrap my mind around the fact that what looked like a hill was a pyramid that, according to Santos, was larger than Tlachihualtepetl, the pyramid in Cholula that, by volume, is the world’s largest.

A few months after I first laid eyes on the pyramid, I took a tour of it organized by Los Guardianes del Teotón, a group of volunteers who explore and protect the pyramid.

“Teotón is a Náhuatl word that means either “great god” or divine god,” Santiago Popoca Fernández told our small group. “This was a very important ceremonial center. It was probably 400 hectares (1,000 acres). The hill was modified by our ancestors; they modified it and made a temple.”

Unlike Tlachihualtepetl, he told us, this pyramid may have been built by covering a hill with stones, somewhere between 850 and 1,000 B.C.

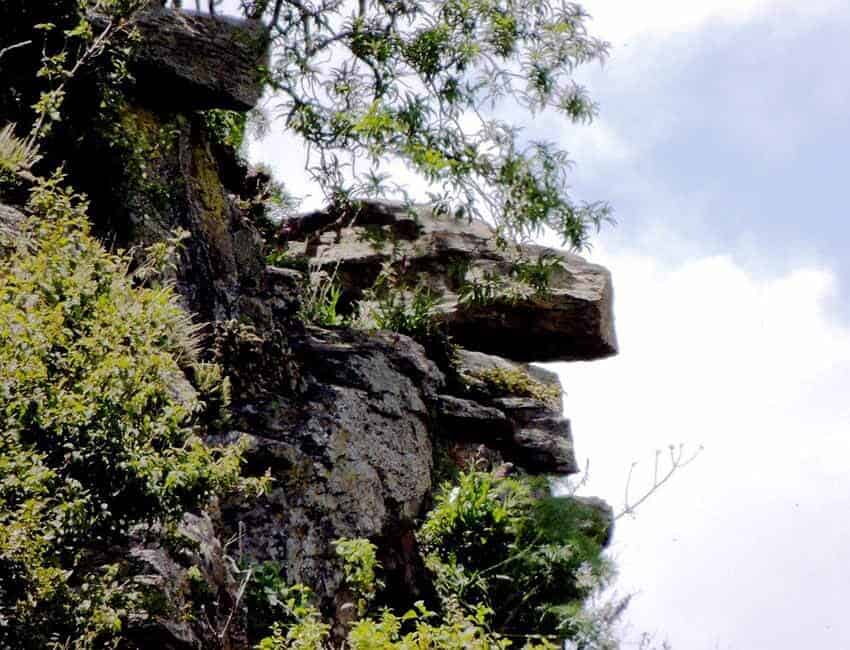

We proceeded up the pyramid, stopping several times along the way.

A very large, flat stone called El Águila stands near Teotón’s top and overlooks the valley below. It’s believed by many San Pedro residents to have been a sacrificial altar, but Santiago strongly disagrees.

“No sacrifices were done on El Águila. This is a place of life,” he said. “We believe that water was poured on El Águila that trickled down the hill. In this area, they probably performed fertility rites. El Águila is protecting the valley, the fertility.”

He did say that there’s a sacrificial stone on top of Teotón, where a small chapel stands. Santiago pointed to El Águila, repeating that it was a place of life, then pointed to the chapel at Teotón’s peak. “That is a place of death,” he said.

Bonifacio Cholula, a local expert on Teotón, believes El Águila was a Neolithic monument.

“It was made when people stopped being nomads,” he said. “It was used for astronomical sightings.”

Below El Águila are two small, adjacent caves facing west; it’s not clear if they’re natural or manmade. One cave has two small niches inside, and the other has one. Idols or offerings were typically placed in niches like these in pre-Hispanic times, says Javier Márquez Márquez, a self-taught expert on pre-Hispanic cultures who has worked with several archaeologists.

When I pointed out a small plaza in front of the two caves, Santiago did a little dance. “It was for priests to dance,” he said.

Several rocks in one area of the site have carvings — thin lines, some of which look like they represent a human figure, maybe a god. Others are indecipherable. I sent photographs of them to archaeologist Juan Zimbrón. Lines as thin as the ones on those rocks are typically made with a metal implement, he said, so they were likely made after the conquest but could still be indigenous and hundreds of years old.

Much of what I’ve learned about Teotón is from San Pedro residents, and almost all of that has been oral history. Oral histories are often very accurate, but until the site is excavated, no one can say for sure what’s there.

I contacted four Mexican archaeologists who work on pre-Hispanic sites, and none of them had even heard of Teotón. A fifth I spoke to had seen it from a distance but has never visited. There’s some information online about Teotón, but most sources simply call it a pyramid without offering any hard evidence.

In a video featuring archaeologists discussing Teotón, however, they show a map believed painted around 450 years ago, known as the Cuauhtinchan Map #2, that has a glyph representing a pyramid where Teotón is located, giving supporting evidence to the idea that Teotón is a pre-Hispanic pyramid mistaken for a natural hill, not unlike how Cholula’s great pyramid was initially mistaken for a mountain.

While Adriana Saenz, an archaeologist who works with INAH in Puebla and who was interviewed in the video, doesn’t believe it was a pyramid, James Brady — an archaeologist with California State University, Los Angeles, who has researched sites in Mexico and throughout Latin America — believes it could be.

“This is definitely elite architecture,” he says in the video. “What does it represent? We don’t know. It does look like it is of considerable size. Could it be a pyramid? Could it be a palace? We don’t know. Is it something important? Obviously. The step glyph on the map is ancient and commonly used to represent a hill, mountain or pyramid.”

The video speculates that Teotón had an astronomical function: on May 15, the day of the zenith sunrise (when a vertical pole casts no shadow), the sun rises over La Malinche volcano in Puebla and Tlaxcala and then strikes the top of Teotón, whose shadow then appears on the Popocatépetl volcano. This marks the beginning of the rainy season and would have indicated that it was time to plant crops.

Although Teotón has had no systematic excavations, residents and archaeologists have found thousands of figures, bowls, pots and other ceramic pieces in the area, including ones from Teotihuacán and from the Mayan and Olmec civilizations.

The presence of pieces from several important cities and civilizations confirms residents’ belief that Teotón was an important cultural or ceremonial center — residents of San Pedro refer to their pueblo as “the first Cholula.”

“Here is the beginning,” said Victor Romero Silva, a Guardianes member. “We believe that here, Cholula was founded, that here Cholula started.”

They believe that whatever indigenous group occupied the area fled when Popocatépetl erupted 2,000 years ago, settling in what’s now known as Cholula. Bonifacio Cholula thinks that whatever Teotón is — and he firmly believes it’s a pyramid — it exerts a powerful force on the area.

“In Teotón, there is no winter,” he said. “There is no ice. And we can have macadamia nuts and peaches because Teotón discharges energy. Because of this energy, there is no winter.”

Sometimes it’s frustrating to know that there may be a pyramid in San Pedro Yancuitlalpan — a pyramid larger than Tlachihualtepetl — that was built by a civilization that we now know nothing about — and will know nothing about because INAH, Mexico’s archaeological agency, lacks the money, or the will, to explore it.

But then I listen to the Guardianes, to Bonifacio Cholula and to other residents of the pueblo, and realize that whatever’s there will be protected and revered. And maybe that’s enough.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.