Mexico’s populist president has turned his guns on foreign investors, the media and the business elite to rally his base and drive an anti-establishment message. But his latest target seems an unlikely one: the body that certified his landslide election victories.

President López Obrador has proposed to slash the National Electoral Institute’s (INE) budget and replace its 11-member council chosen by political consensus with seven directly elected delegates. He also wants to save money by cutting the size of Mexico’s Senate by a quarter, its lower house by over a third and ending public financing of election campaigns.

The opposition and independent observers have cried foul, saying the changes would destroy the INE’s independence and undermine confidence in Mexico’s young democracy, which emerged from 70 years of one-party rule only in 2000.

“It’s a reform which is not necessary because what we have today works well,” INE president Lorenzo Córdova told the Financial Times in an interview. “As the English-speaking world says: ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’”

Mexico will hold the biggest elections in its history in 2024, choosing a new president and Congress, eight state governors, the mayor of Mexico City and 31 state legislatures. López Obrador wants to push the constitutional changes needed to reconfigure the INE through Congress this year, though he faces stiff opposition.

“If the INE really is damaged, it would be a disaster,” said Enrique Krauze, a Mexican historian and commentator. “The future of the INE is the biggest worry in Mexico right now.”

López Obrador lacks the necessary two-thirds majority in Congress but opponents worry that even if he does not succeed in tailoring the INE to his liking, he will have tarnished the institute’s reputation enough with his attacks to mount a credible challenge to the 2024 election result if his candidates lose.

Córdova, an earnest academic who has run the electoral body since 2014, is keen to avoid stoking conflict. But he points out that during his tenure at the INE, López Obrador won the presidency by a landslide while his Morena political movement won half of Mexico’s state governorships, with more victories predicted in state elections this month.

“How is it possible that in this period of eight years, in two of every three elections held, there has been a change of power . . . the party which has benefited most has been Morena,” he said. “In truth . . . the main problem the president sees is that this is an autonomous institution which doesn’t bend to political power.”

López Obrador has been gunning for the INE since narrowly losing the 2006 presidential election. He claims that his proposed changes would eliminate fraud, “stop dead people from voting” and save over US $1.2 billion. The move, announced in April, has not yet been voted on in Congress.

The left wing veteran’s assault on the electoral body comes after a string of attacks from the president on Mexico’s fragile independent media, the Supreme Court, the central bank, foreign investors in the energy sector and others he sees as opponents of his so-called “transformation” of Mexico.

“This proposal comes at a time when López Obrador has been actively undermining democratic guarantees, such as judicial independence and the essential role of independent journalism and civil society,” said Tamara Taraciuk Broner, acting director of Human Rights Watch Americas. “It is critical that any electoral reform is the result of an open public discussion and that it does not limit fundamental democratic guarantees that Mexicans fought for decades to win.”

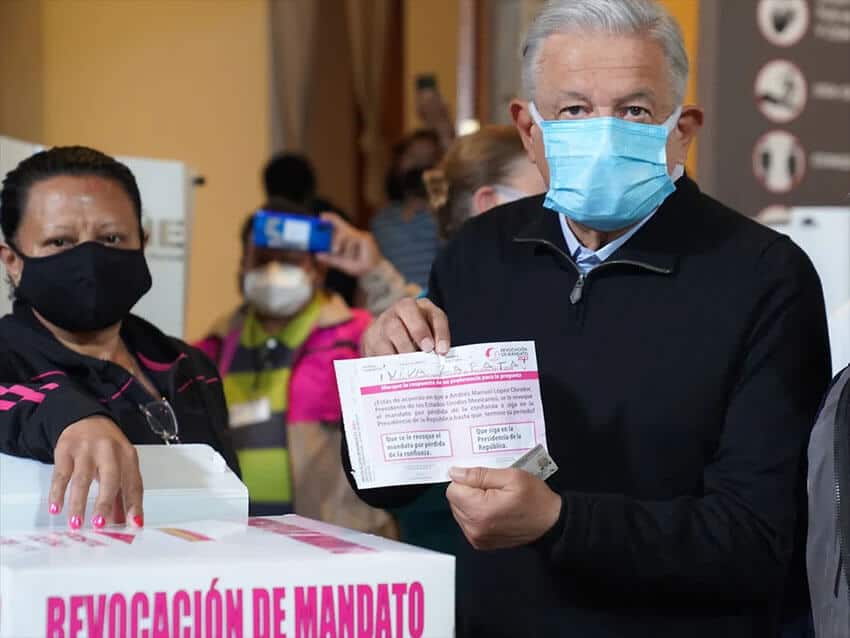

Córdova faces pressure on other fronts. The government slashed 26% from his budget request for this year, leaving the INE short of the funds needed to run a presidential recall referendum designed by López Obrador (the president won the contest in April easily on a low turnout).

A ruling party candidate for governor of Guerrero state, Félix Salgado Macedonio, threatened Córdova publicly at a demonstration held outside the INE in April while it was deciding whether to bar him for failing to report campaign spending. “Wouldn’t the people of Mexico like to know where Lorenzo Córdova lives?” Salgado asked the crowd, speaking on a makeshift platform which included a coffin with the name “Lorenzo” on it.

The Morena-appointed president of Congress, Sergio Gutiérrez, last year filed a criminal complaint against him and five other INE directors over the conduct of the recall referendum, breaking what Córdova says is an unwritten rule dating back decades that INE officials should answer only to an electoral tribunal, not the courts.

But despite the attacks, the INE continues to win the trust of nearly 70% of citizens, according to polls. Córdova has won popular recognition for his stout defense of the institution and is greeted in the street or in restaurants by well-wishers.

Conscious of his brief to uphold impartiality, the INE chief is reluctant to attack the government directly or to play up the problems his institute faces. But when pressed on whether Mexico’s young democracy is in danger, he answers:

“There is an institutional strength which allows us to say that democracy in Mexico has the force needed to face challenges — but evidently we are facing unprecedented challenges.”

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email.