The word “surrealism” was first mentioned in Parisian poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s critique of an abstract ballet in 1917. A few years later, another French poet André Breton transformed it from a mere morpheme to an actual movement. In Breton’s words, surrealism worked to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.”

Its origins had nothing to do with visual art, and more to do with automatic, free-form writing to access the deepest recesses of the brain, chronicled in Breton’s 1924 book “Surrealist Manifesto”. Such an undertaking appealed to the eclectic minds of Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró, and the movement took flight.

Landing, as it were, in Canada. Twenty years later.

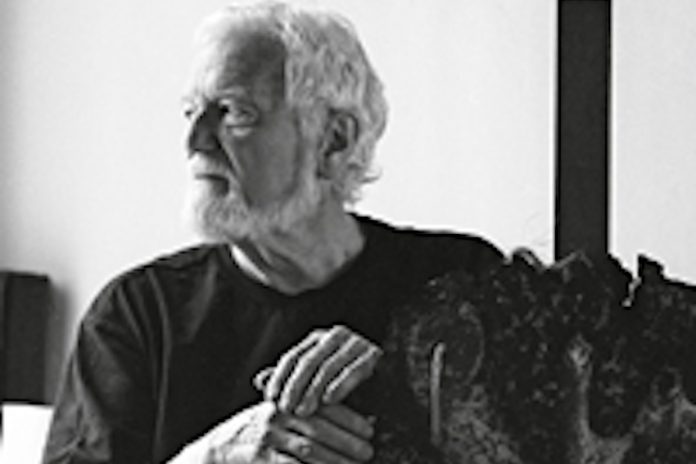

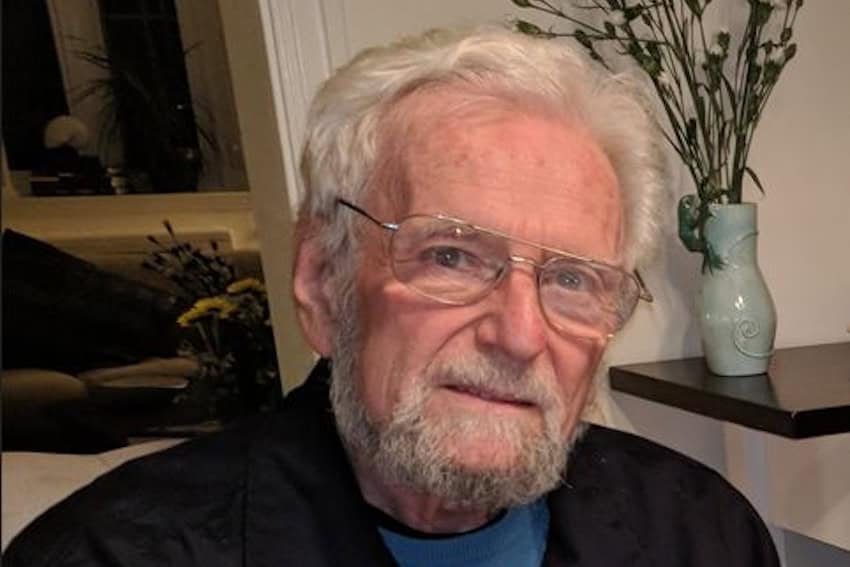

At the time, Alan Glass was about ten years of age. His father had been a golf pro who invented the wildly unsuccessful square golf ball. Whether or not this freedom of artistic expression had a direct influence on Glass’ eventual career, we can only assume. He enrolled in École des Beaux-Arts in Montreal, perfecting his skills under the mentorship of Alfred Pellan. In 1952, he visited Paris to exhibit some of his creations at the Galerie Le Terrain Vague. It was here that Glass met Bretón, and his life changed forever.

He would spend the next ten years in Paris, hobnobbing with the world’s greatest artists and traveling extensively despite a starving artist’s salary. With the quirky items he picked up on his travels throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, he created unique mixed media sculptures. Glass would, in a fit of nominative determinism, fill glass boxes with trinkets such as wires, buttons, threads, and seashells, arranging them in an unusual yet carefully coordinated way.

One day, Glass spotted a small sugar skull in a friend’s studio, outrageously decorated in bright colors and beads. This little creation hailed from Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebrations. Enthralled by what he had found, he went in search of more, arriving in Mexico in 1962.

Upon Glass’s arrival, classic surrealism had already reached its peak in Mexico. Artists like Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo used the colorful daily life of Mexicans to etch out surreal masterpieces. Their art often showcased political and social statements, as well as a surge of cultural appreciation, with heavy reliance on Mexico’s indigenous history. Glass was enamored with the vivid imagery and felt the pull to return the following year. From 1963, he lived permanently in Mexico, working alongside Carrington and meeting a circle of expat surrealists lincluding Pedro Friedeberg and Kati Horna.

His art became increasingly more dream-like and expressionist, as he embraced the country he openly declared he was destined to live. A collector of things since childhood, Glass’s house in Mexico City’s La Roma neighborhood was brimming with stuff – notably plants; Mexican poet Alberto Blanco once described it as “a greenhouse full of exotic plants I’d never seen”. It’s no surprise that, toward the end of Glass’s tenure here in the real world, he had increasing concerns about the effects of technology on society, citing its disruption of our ability to dream.

Over his years in Mexico, Glass produced countless 3D collages including La Unidad del Multiple, which he worked on between 2003 and 2005. Known by many as the “last surrealist,” Glass was recognized with the prestigious Medalla Bellas Artes in 2017. In 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, he created “Zéro de conduite” featuring an old, frayed Mexican world map scattered with broken eggshells, paper scraps, and wrinkled face masks.

He died in Mexico City last year at 91 years old after a full, vibrant life shaping the surrealist art world.

His romantic life is tightly under wraps. Whether or not he had any great loves aside from his art remains as mysterious as the inner workings of his fascinating mind. Well, that’s not totally true. As we know Glass was wholly in love with Mexico.

Today, you can find his art on display at:

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

- Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville in Paris

- Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City

- Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in Canada

This article is part of Mexico News Daily’s “Canada in Focus” series. Read the other articles from the series here.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog, or follow her on Instagram.