These words are found in the Introduction to San Miguel de Allende resident Janet Sternburg‘s photography book. I found them striking: “In Mexico, so much lives together.”

“So much photography is about isolating what is, framing it in its uniqueness, its apartness. In Mexico, so much lives together, with a greater tolerance for ambiguity and a sense that nothing should be isolated.”

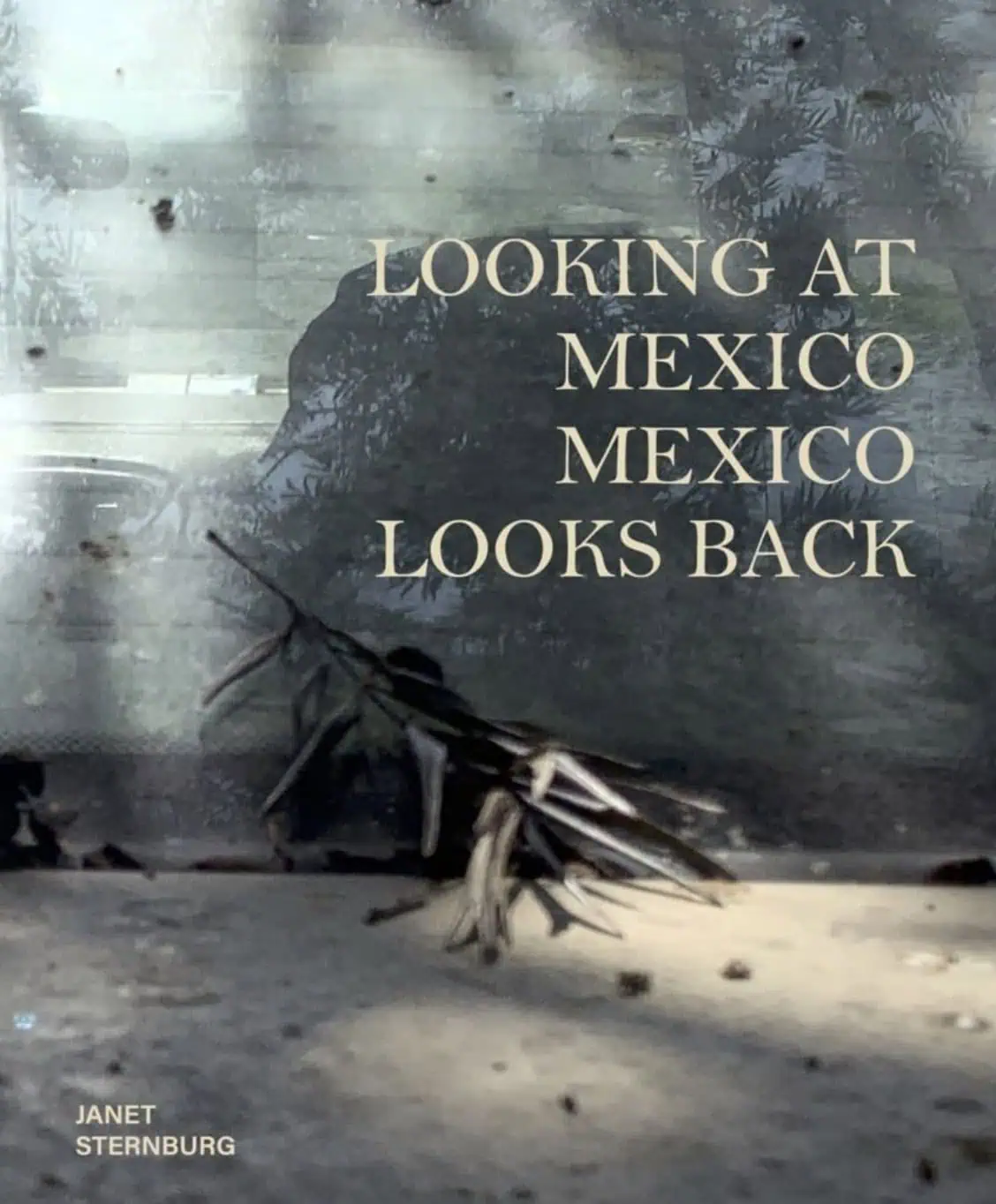

Sternburg’s book, Looking at Mexico, Mexico Looks Back is the perfect illustration of this and a beautiful example of bicultural and bilingual collaboration. While the photographs are her own, the commentary is by a friend drawn in by her photos: Jose Alberto Romero Romano.

And this is part of what makes the book so unique. First, all of the commentary is given in both English and Spanish. And second, the commentary is by someone who is from Mexico, who sees the images not as things foreign and strange, but as familiar. Romero’s poetic prose — sometimes description, sometimes stream of consciousness — provides a fascinating glimpse into the feelings and associations behind the images.

In a world now filled with AI images and glossy brochures of resort living, it’s refreshing to see scenes unposed. Throughout the book, walls stand. People go about their business. Objects sit on surfaces. The subjects of the photographs simply do what they will, without regard for the camera. “Leaving things be” when it comes to an aesthetic field like photography can constitute a radical act.

This book does not allow the perception of Mexico to be consumed by caricature: no smiling child with perfect teeth holds up perfectly formed artesanías before a frothy green background. No slick “top ten reasons to move to Mexico” marketing copy. These photographs and commentary are simply “slices of life”.

Below are excerpts of some of my favorite photographs with their commentary in English:

![]()

“When I was a little boy in the shower, my grandmother used to scrub me with these. I remember water on the floor. These pads are called “estropajos” and they’re something that Mexicans have in common. At first to a child they’re big and hard, but this changes with time. After they’re used for a while, they get softer and their name changes to “zacatitos.” Now they have become part of our identity. They make us feel a connection to being Mexican.”

![]()

“This man is not a warrior. He is a dancer, maybe during the day he’s a taxi driver. But when he wears this mask, the crocodile talks through him. This gives him power.”

![]()

“This is very personal. For the person who made it, it doesn’t matter who likes it. Even if other people think it’s horrible, he doesn’t care. “It’s what I like.” It’s not there as a car, it’s his unique identity.”

![]()

“My grandmother does the same thing. It’s not like she’s casually sticking a photo in a frame. She puts as many as twenty or thirty small photographs along the side of a picture. After the natural birth of our son at home, my wife felt exhausted. My grandmother remembered how it felt when she had her child, and offered my wife a traditional remedy to recover the energy of her body and soul. She said, ‘Take a bath with flowers.’ It worked. My wife got better. She was accepted by my grandmother. This is why a photograph of my wife is included among the others. My grandmother is saying to the Virgin, ‘Please take care of my son, and his wife and child.'”

![]()

“Struck by lighting, this tree is wounded. But it has healed itself. It’s alive. In this photograph, I can see a turning point. In one moment, a bolt can change the structure of the tree, its “personhood,” its identity as a tree. The world becomes before and after the lighting. This is like life, the moment of a child being born that changes everything afterward.”

![]()

“Like a telescope, this window is another portal. The moment of a photograph is the moment to open your heart. This is an image at the end; it is also an image of return. Now you go through the portal. The child, me, in a shower, being scrubbed, that is you too.”

As someone who’s never felt quite comfortable with all the glossy promotion of Mexico which so often seems to breeze past the experiences of those who actually live here, I was happy to take a peak into something that felt truly genuine.

The book now lives on my coffee table, ready to be picked up and browsed through when the Instagramafication of the world feels too strong a force.

For a different look at Mexico, pick it up.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.