A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about “gaming the system” in Mexico: that is, taking advantage of the ability to earn in — or draw income from — one economy, and live and spend in another, one with a much lower cost of living. It’s a topic I’ve written about many times before. But this one seemed to strike a nerve.

In the comments section, many readers took issue with the phrasing, particularly. I’d sum them up like this: “We learned Spanish, we treat people well, we’re involved in the community, we do volunteer work. How crass to equate our way of life with cheating!”

One of the topics I addressed was the inherent unfairness of the economic systems that make living in Mexico a “good deal.” Here’s what I mean.

As a U.S. citizen, I have access to online jobs — albeit precarious ones — that are only open to U.S. citizens. Because these jobs are for U.S. citizens who presumably live in the U.S., the pay is adjusted to the cost of living there. Mexican jobs, on the other hand, are paid considering the cost of living here, which is much lower.

In neither place are most average salaries quite enough to live comfortably, which accounts for some of the migration south.

That means that as a professional in my field, I can earn much more than a professional Mexican in my same field, despite that professional Mexican being just as smart, just as educated, and just as hard-working as I am. While I might live like a queen, they barely scrape by.

Here’s an example: one popular Mexico-based online job is to work as a phone interpreter. To do this job, you must be completely fluent in both languages, which trust me, is no easy feat. You also have to be computer savvy, extremely sharp, and quick on your feet. I myself am fluent in both languages, but wouldn’t dream of trying to work as a live interpreter: it’s too hard, and I’m too spacey. The wage for this extremely high skill that takes years to master? About US $850 a month.

“That’s not a bad wage here,” you might say. I suppose not, especially if you don’t have to pay rent and there are other workers in your household. But it’s nowhere near comfortable, especially if you live in a large urban area. Ask yourself honestly: how well could you live here on that amount, especially if you didn’t already own a home or vehicle?

Now, Mexicans do have plenty of “home field” advantages that offset some of this. Immediate family support and property is a big one, for example. Still, none of us can escape the need for money, and the more you have, the easier things get.

By extension, it means I — we — often have much more economic power than they do, despite not being measurably “better” or more deserving than they. We can buy more. We can afford to live in the best areas.

And while this is, let’s be honest, an inherently unfair system, it’s of course not the fault of any one individual. Building and maintaining a system is one thing; taking advantage of it as a worker is another, very human by the way, thing.

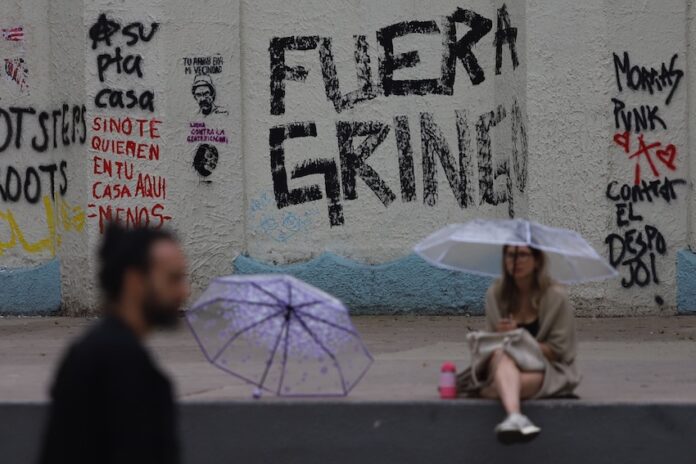

Like, I’m sure, many of you, I watched with dismay as the “anti-gentrification” protests played out in Mexico City last week. Most of the protests, let it be said, were peaceful, if a bit rude. “Gringo go home?” Ouch. But some parts were scarier, with actual violence. One particular video clip haunts me: a blonde woman who looks a lot like me ducking in a restaurant as angry protestors lurched toward her.

Yikes.

Any therapist will tell you: the emotion behind anger is always fear born of deep pain.

The issue at hand here is principally the question of who gets access to scarce resources. In this case, the “scarce resources” are the trendiest neighborhoods of Mexico City.

The last time I went to that area of Mexico City was in 2021 to renew my kid’s passport. It was a gorgeous urban landscape with parks and cute cafes everywhere. There were white people everywhere I looked. A trip to the panadería for what would have cost 35 pesos in our own city cost over 200 there, leaving our eyes watering at the checkout counter. “Wait, where are we?”

A place where only the rich can afford to live and play, that’s where.

And that’s the kind of thing that can make lots of people mad — especially if they’ve recently been priced out, which, according to reports, did not make up the majority of the protestors.

Was there some xenophobia at play? Certainly.

But officially, those present were protesting “gentrification,” the process by which an area becomes desirable. Once it does, more people move and open businesses there. As the area increases in popularity, alas, so do its prices. This is true in popular cities all over the world.

Now, I feel there’s an important point to make here: no one is moving to an area and insisting on paying higher prices there. Consumers, as a rule, do not set the prices of what they buy; sellers do. And most of the sellers and business owners in these areas are Mexican.

Really, these angry young people are protesting not against foreigners, but against something much more insidious: unregulated capitalism. It allows prices for basic needs like housing to skyrocket. It allows wages to stay much lower on one side of the border than the other for the same work. It ensures that the nicest, choicest parts of any city are reserved almost exclusively for the well-to-do.

But the protestors can’t see the people who are deciding to evict current tenants in favor of those who will pay big bucks for short-term rentals. They don’t see those who decide that a piece of bread from the panadería will cost 30 pesos instead of five. Capitalists everywhere are clever: they mostly stay out of view, away from any potential wrath.

What they can see are people from other places blithely enjoying these things that they cannot. The fact that some are oblivious to the culture and language surrounding them does not help the matter.

You can’t yell at the concept of real estate speculation or capitalism in the street. But you can yell at a foreigner.

It is obviously not nice for anyone to treat anyone else as a villain because of the way they look or as a result of their foreigner status. It is wrong, and it is sad. And it’s 100% something that white people from North America are not used to dealing with. I’m not saying we’re cosmically due, but it does seem a little unfair, in the grand scheme of things, that one group should be indefinitely exempt from xenophobic treatment.

It’s worth remembering too that Mexico City, with Claudia Sheinbaum as mayor, rolled out the welcome mat for these foreigners by partnering with AirBnB and UNESCO in 2022. Overall, it wasn’t a terrible plan. After all, Mexico depends on tourism for a significant portion of its GDP.

But tourism money coming in is not spread about equally. While you could argue that a low-paid hotel maid benefits from having a job, the real winners are always those who own the places where they land and play.

And when enough people take notice that those left on the outside looking in far outnumber those benefiting, people get upset.

And when lots of people are upset together, rationality does not reign. Be careful out there.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.