By February 1768, the Jesuits, expelled from Spanish dominions by King Carlos III for reasons that remain unclear — one theory was that a forged letter ostensibly from the Jesuits questioned the legitimacy of the king’s birth — were gone from the Baja California peninsula. However, any ideas of the hidden wealth of the Jesuits — another charge often made by their enemies — were quickly dispelled.

When Gaspar de Portolá, the new California governor, sailed into San José del Cabo on Nov. 30, 1767, “the soldiers, who had come with exaggerated notions about the wealth of the Jesuit missions, hastened to seize the treasures of Mission San José del Cabo; but, with the exception of the church ornaments, nothing of value was discovered,” wrote Zephyrin Engelhardt in his 1908 book on the Spanish missionary period, “The Missions and Missionaries of California: Vol. 1, Lower California.”

“They then proceeded to Mission Santiago and encountered the same poverty. Like all the Jesuits in the missions, Father (Ignacio) Tirsch of Santiago had not the least suspicion of what was coming, and no reason or opportunity for concealing anything. Portolá next took his men to the silver mines and convinced himself of their poverty, and the penury of those who feebly worked them.”

José de Gálvez and the shift in Franciscan focus

After a little more than 70 years of missionary work on the Baja California peninsula, the Jesuits had accumulated no wealth but had founded 17 missions and “saved many souls.”

The Franciscans, who replaced them, would remain in Baja California for only five years, establish only one mission — the Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá, about 35 miles southeast of El Rosario — and leave the peninsula’s missions even poorer than they already were.

The Franciscans were chosen as successors to the Jesuits by José de Gálvez, the visitador general, whose newly endowed authority had made him the most powerful man in Mexico (or Nueva España, as it was then known).

Gálvez arrived in July 1768 to reorganize the peninsula, unveiling his plans for California to the dozen or so Franciscan friars, led by Mallorcan Junípero Serra, who himself had only been in residence since April.

The most ambitious of these plans was the commitment to establishing missions in Alta California — now the U.S. state of California. How much of this shift in focus northward was influenced by the evident poverty of the missions in Baja California is unknown. However, by early 1769, land and sea expeditions were bound for San Diego. By July of that year, Serra had founded the first Alta California mission there. Serra would later found eight more missions in Alta California, an achievement for which he has since been controversially canonized as a saint by the Catholic church.

Portolá, also integral to the expedition, saw his role as governor expand to include both Alta and Baja California.

How Baja California paid for the settlement of Alta California

Not everyone benefited from this northern focus, which by 1777 had seen the capital of Las Californias shift from Loreto in Baja California to Monterey in Alta California. To be blunt, the settlement of Alta California was largely paid for by looting the meager coffers of Baja California’s missions and squeezing money from the peninsula’s lone successful entrepreneur.

“To lessen the expenses for the proposed missions, Gálvez decided that the old establishments (the missions in Baja California) should aid in founding the new ones by donating vestments, sacred vessels and other church articles,” Engelhardt wrote. “From the inventories, he saw that all could assist a little, which, with what he had obtained from the extinguished missions, would supply at least three new missions. He himself proceeded to Todos Santos to collect what could be spared, and he directed Fr. Serra to do likewise on his trip to the north from all the missions, not excepting Loreto.”

Also contributing was the one rich man the peninsula had so far produced: former soldier Manuel de Ocio. After reaping some timely intel from Cochimí Indians about 400 pounds of pearls thrown onto a beach in Mulegé after a violent storm in 1740, Ocio retired from the Loreto presidio to found a mine at Santa Ana in 1748, a few miles south of the Baja California Sur mining towns that subsequently sprang up in San Antonio and El Triunfo.

Ocio’s mine wasn’t that impressive in terms of the amount of silver it produced, but by 1751, it had reached the limit necessary for him to register it with the Spanish crown and pay taxes. In addition to the workforce of 300 he acquired, many from the Mexican mainland, he also ran thousands of head of cattle and managed to buy 14 homes in Guadalajara as a real estate investment.

Gálvez, seeing that Ocio had what little wealth there was on the peninsula, established his headquarters at Santa Ana and ruthlessly pumped the mine owner to help fund the expedition to Alta California. Indeed, according to Harry W. Crosby’s definitive book, “Antigua California, Mission and Colony on the Peninsular Frontier, 1697-1768”:

“Manuel de Ocio’s little empire provided the ship that made possible Portolá’s coming; the further use of his ships, his mules, mule drivers and stores made possible the prompt launching of the expedition to the north. Without that which was commandeered from Ocio, Gálvez’s plans would have had long setbacks. But Ocio received no thanks and ultimately no reward nor even the recompense promised by royal officials.”

As if that weren’t bad enough, two of Gálvez’s imported miners murdered Ocio in 1771 after robbing his storehouse.

Indigenous peoples and the disaster of Gálvez’s policies

If Ocio was ill-used by Gálvez, so, too, were the Indigenous peoples of the Baja California peninsula. Gálvez believed the Jesuits had coddled the Indians; he was intent on using them as a free labor source, including in the salt mines at Isla del Carmen, off the coast of Loreto.

“Gálvez made elaborate plans for the transformation of the California missions using Serra and the Franciscans as the agents for the changes he thought necessary,” author Dave Werschkul pointed out in “Saints and Demons in a Desert Wilderness: A History and Guide to Baja California’s Spanish Missions” (2003):

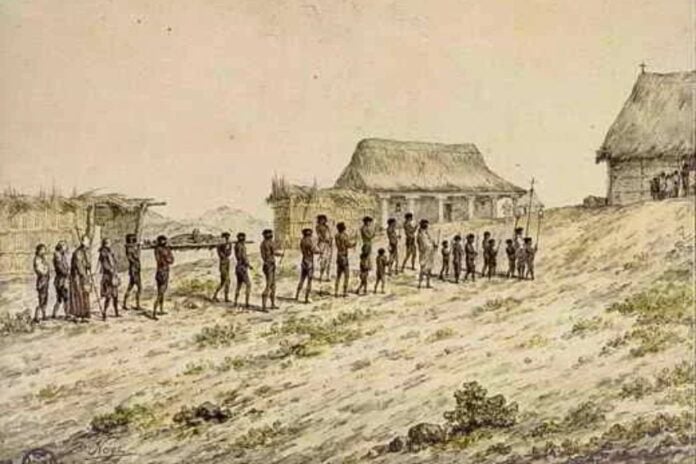

“Among Gálvez’s decrees were the reduction in the number of missions, elimination of the visitas (sub-missions), and the movement of Indians from one area to another to meet the labor requirements of the more productive agricultural areas. The results were a disaster. In 1769, one ranchería of 44 Indians was moved from San Javier to San José del Cabo. All but three died.”

The native inhabitants of Los Cabos, the Pericú, also saw their numbers continue to dwindle. In 1768, the year the Franciscans took over, there were 178 Indians at the Santiago mission under Fr. José Murguía and 70 at San José del Cabo, which had been raised back to full mission status under Fr. Juan Morán. Three years later, in 1771, those numbers were 70 and 50, respectively, or a total of only 120 throughout Los Cabos.

Likely, these were mostly still Pericú, although as noted above, Gálvez was not above importing Indigenous people from other parts of the peninsula to help facilitate agricultural production for the missions.

Disease remained the primary culprit for the diminished numbers. Many Indigenous people were killed by the 1769 epidemic that also killed Fr. Morán, as well as the French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Chappe d’Auteroche, who had traveled to San José del Cabo to observe the 1769 Transit of Venus, which he did successfully before his death.

The exact disease that decimated Indigenous numbers is not known. An outbreak of measles was known to have occurred that year, with typhus and yellow fever also conjectured.

The Franciscan era’s legacy in Los Cabos

The Jesuits had been careful to keep the population of Baja California restricted to missionaries, Indigenous and presidio soldiers. Some soldiers were married. Esteban Rodríguez Lorenzo, for example, one of the original 10 to land at Loreto in 1697, married María de Larrea on the mainland during a hiatus from his duties in 1707. They had seven children, the first true family of settlers on the peninsula. Rodríguez was also the first man permitted by the Jesuits to raise his own cattle.

But as local historian Pablo L. Martínez was quick to note in his “Guía Familiar de Baja California, 1700-1900” (1965), the first real secular community to arise on the peninsula came about because of the need for workers at Ocio’s mine. Santa Ana thus became a kind of cradle for early settlers, with some of the most esteemed Los Cabos families, such as the Cotas, arriving during this early period.

Gálvez, for all his faults, was the first to initiate a call for colonists.

“Besides making strong efforts to improve the conditions of the natives, Gálvez paid special attention to the project of colonizing Lower California with Spaniards,” Engelhardt wrote. “On Aug. 12, 1768, he issued a decree setting forth the privileges offered to colonists and the regulations by which they were to be governed. Government lands were separated from mission lands and offered to Spaniards of good character on easy terms.

“The chief obligation was that the settlers would make improvements and pay a small annual tax to the king. The first to avail themselves of these advantages were discharged soldiers and sailors from Loreto, but there were few others before 1821.”

These discharged soldiers, sailors and their families, along with the workforce at Santa Ana, would form the roots of the communities that would eventually arise in San José del Cabo, Cabo San Lucas and elsewhere in the region now known as Los Cabos.

But, first, there was one more Catholic missionary order to come to the area — that of the Dominicans, who took over the missions in Baja California after 1773, when the Franciscans decided to concentrate their efforts solely on Alta California.

Chris Sands is the former Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best and writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook. He’s also a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily.