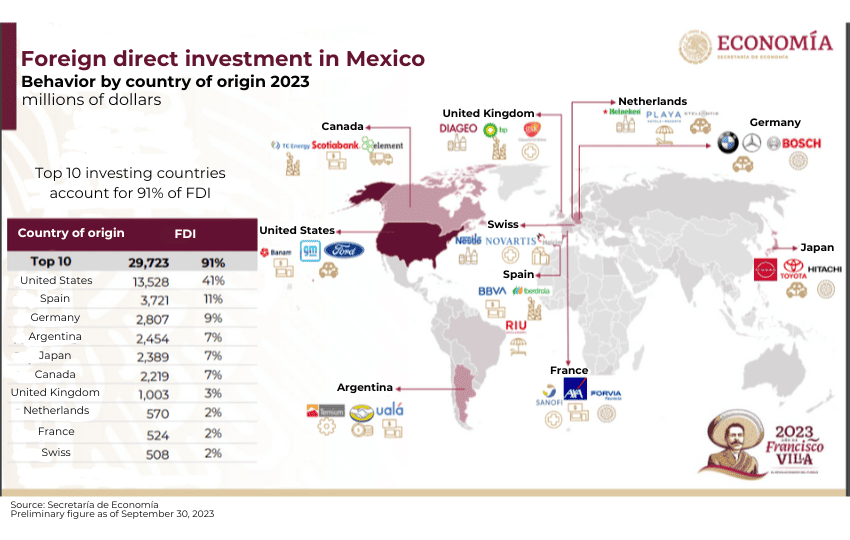

When the Economy Ministry (SE) published foreign direct investment (FDI) data earlier this month, one country was conspicuous by its absence in the list of the top 10 investors in Mexico in the first nine months of 2023.

The United States was there, of course, occupying its entrenched position at the top of the list.

Spain was there, Germany was there, Japan was there, Canada was there, but China — the world’s second-largest country and an emerging superpower — was not.

That was surprising because numerous Chinese companies have announced investments or started operations in Mexico this year: Noah Itech in January, Xusheng in May, Asiaway in June, to name a few.

So why did China fail to crack the top 10 when, as the Economist reported last weekend, “Chinese investments have been pouring into Mexico lately”?

In this article, I’ll seek to answer that question and explore a couple of other issues related to Chinese investment in Mexico.

Investment announcements don’t immediately show up in FDI data

According to Integralia, a Mexico City-based consultancy that tracks foreign investment in Mexico, Chinese companies made 19 investment announcements totaling US $8.14 billion between January and November.

In the Economy Ministry’s FDI data for the first nine months of the year, Chinese investment wasn’t even reported as it was below the $500 million threshold required to get into the top 10.

Based on the $8.14 billion figure — which takes new (as yet unrealized) investment announcements and facility inauguration announcements into account — China is currently the second largest foreign investor in Mexico behind the United States.

However, money tied to investment announcements — including US $5 billion announced by Lingong Machinery Group last month — takes time to show up in SE data as the funds don’t immediately flow into the country, and in some cases never arrives because the project is canceled before it begins.

As Gabriela Siller, director of economic analysis at Banco Base, noted on the X social media platform on Monday: “There are a lot of announcements, but that doesn’t equal investment.”

Of course, Lingong’s $5 billion announcement couldn’t show up in the SE’s data for the first nine months of the year because it was made in October. It will likely take a considerable amount of time before the entire investment amount is reflected in official statistics.

The government of Nuevo León — a nearshoring hotspot that is popular with Chinese investors — “says billions in investments that have been announced there are not yet reflected in FDI figures and exports,” according to a Financial Times report published Sunday.

Some Chinese money is never counted as such

Some Chinese investment in Mexico isn’t reflected in SE data because the money comes into the country via United States subsidiaries of Chinese companies, according to Enrique Dussel Peters, an economist and coordinator of the Center for Chinese-Mexican Studies (Cechimex) at the National Autonomous University.

The FDI inflow is thus recorded as coming from the United States, when for all intents and purposes the money came from China.

Between 2001 and late 2022, the Economy Ministry recorded some $3 billion in Chinese FDI to Mexico, but according to Cechimex, the real figure for that period is around $17 billion.

“It’s almost six times higher!” Dussel told the El País newspaper. “It’s not 10% more or 5% more, but 500% more.”

The establishment of joint ventures between Chinese and Mexican companies can also skew Chinese FDI figures in Mexico.

Why Mexico? Why now?

The Economist reported Saturday that “Chinese companies’ heightened interest in Mexico dates to 2018 when Donald Trump, America’s president at the time, launched a trade war that included raising tariffs on imports from China.”

U.S. President Joe Biden has kept those tariffs in place, and his “America-first policies, such as the Inflation Reduction Act, are encouraging companies to consider ‘nearshoring’ in North America, in large part to thwart China,” the London-based publication said.

“The irony,” Dussel Peters told The Economist, “is that the first to react positively to an explicit policy against China are Chinese firms.”

Mexico courted Chinese investment in 2008 when the Mexico-China Chamber of Commerce and Technology organized a series of events, but the attempt to attract more Chinese capital was unsuccessful, according to the chamber’s vice president César Fragozo.

“Back then,” The Economist reported, “China had no need to use Mexico as a way into America, which had yet to turn its back on Chinese companies.”

But 10 years later, with Trump in the White House, things changed. In the years since 2018, Mexico has become more attractive than China for many manufacturers for a variety of reasons, including geopolitical ones, rising wages and costs in China, supply chain issues and other factors related to the COVID pandemic.

Mexico gives China “a back door” into the United States because along with the U.S. and Canada it is party to the USMCA free trade pact, The Economist noted.

“Depending on what components they use, Chinese companies based in Mexico cannot enjoy all the benefits of the trading bloc, whose rules dictate what percentage of a product must originate in North America. But, Mr. Dussel Peters notes, the average American tariff on imports from Mexico in 2021 was 0.2%, far lower than on those from China,” the publication said.

The Economist also noted that Chinese investors “have learned to deal with the challenges of working in Mexico, such as insecurity and poor infrastructure.”

Is increased Chinese investment a threat to the Mexico-U.S. relationship?

A growing Chinese presence in Mexico “could backfire if it raises tensions with the United States,” The Economist reported.

Some U.S. lawmakers have already expressed their dissatisfaction with the presence of export-oriented Chinese companies in Mexico.

A bipartisan group of United States representatives wrote to U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Katherine Tai earlier this month to urge the Biden administration to raise the current 25% tariff on Chinese vehicles and request that it be ready to “address the coming wave of [Chinese] vehicles that will be exported from our other trading partners, such as Mexico, as [Chinese] automakers look to strategically establish operations outside of [China] to take advantage of preferential access to the U.S. market through our free trade agreements and circumvent any [China]-specific tariffs.”

“Indeed, [Chinese] automakers BYD, Chery, and SAIC Motors have already established themselves in Mexico,” the lawmakers continued.

The four members of the Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party including chairman Mike Gallagher also said in their letter that they are “concerned by how the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is preparing to flood the United States and global markets with automobiles, particularly electric vehicles, propped up by massive subsidies and long-standing localization and other discriminatory policies employed by the PRC.”

“… We look forward to USTR’s response on whether the current rules of origin in our trade agreements need to be strengthened and what other policy tools are needed to prevent the PRC from gaining a backdoor to the U.S. market through our key trading partners,” they said.

The Economist said that if China “is too successful in skirting tariffs it may find its back door as well as the front entrance slammed shut.”

Writing in Mexico News Daily last month, Travis Bembenek argued that Chinese investment in Mexico “is a good thing” in a scenario in which China and North America “soon return to ‘normal’ relations in which there is good communication, trust, and cooperation between both regions.”

However, if Sino-North American relations further deteriorate, “North American countries need to urgently get more serious and coordinated with a plan for Chinese investment into the region,” the MND CEO wrote.

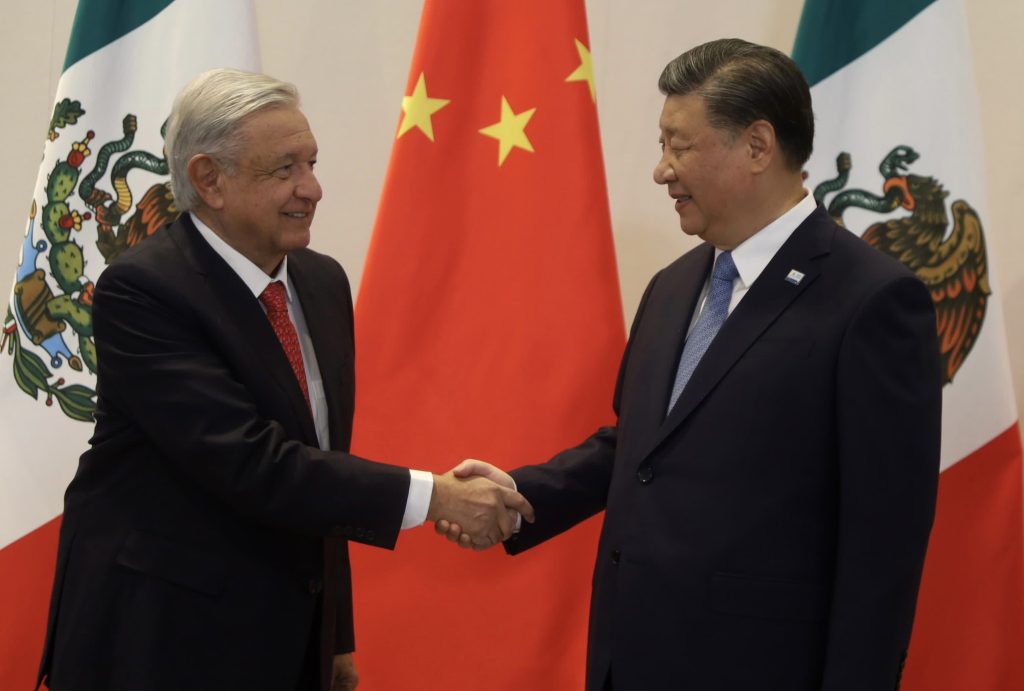

If the United States-China relationship worsens — in spite of Biden’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in San Francisco earlier this month — and Mexico, in the absence of a regional plan, continues to welcome Chinese companies while defending their right to benefit from the USMCA, it is conceivable that Chinese investment here could indeed put a strain on the bilateral relations between Mexico and the U.S.

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies (peter.davies@mexiconewsdaily.com)