“Words are powerful. Every March, I put the rest of my work on hold and do this project because it’s that important to me.” —Kate Van Doren, artist

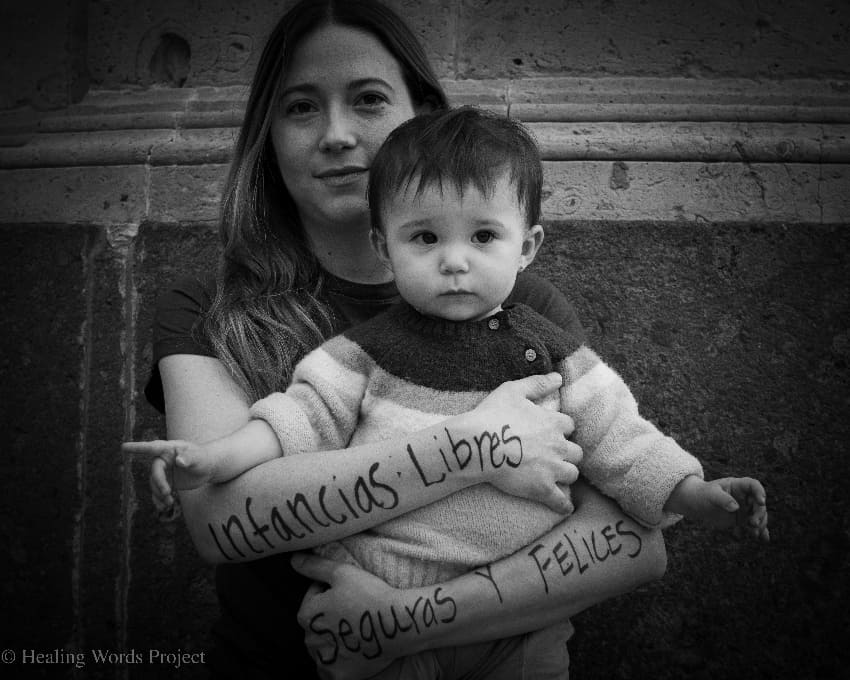

Artist and art therapist Kate Van Doren invites participation in her Healing Words Project in San Miguel de Allende again this year. The project draws particular attention each March around International Women’s Day (Mar. 8), when women are photographed with empowering words of their choosing inscribed on their bodies.

The Healing Words Project was born in the lead-up to the 2020 national women’s strike, Un día sin mujeres (“A day without women”), a protest against the epidemic of violence and femicide (defined as the murder of a woman on account of her gender) in Mexico.

Van Doren noticed women’s posts on social media encouraging each other to temporarily “disappear” on Mar. 9, by staying home from work and refraining from participating in the country’s economy for one day.

During this time, Van Doren also attended the Zona Maco international art fair in Mexico City, where she was impacted by the visceral work of a feminist artist who sewed words of protest into the clothing of women and children.

“I almost dropped to my knees and couldn’t move from the spot,” Van Doren told me. “When we’re exposed to art, it impacts us on multiple levels, subconsciously as well as consciously. The messages I took in affected me deeply.”

The experience provided inspiration, and the upcoming women’s strike imbued Van Doren with a sense of urgency. “That’s when I felt compelled to act. I had a dream that women would write on their own bodies instead of on clothing.”

After the first few photos were seen, increasing numbers of women asked Van Doren for a photo of their own to post on social media as a signal to other women that they planned to participate in the upcoming strike. The project went viral.

Ser Mujer, a San Miguel women’s activist group, took notice. Ser Mujer had a flash mob in the works for International Women’s Day, and through a government contact, the group obtained a list of women murdered in the state of Guanajuato in the previous year. “We wrote the names and ages of murdered women on dancers’ arms,” Van Doren explained, “along with words of reclamation and empowerment.”

Van Doren photographed hundreds of women on the day of the flash mob, and hundreds more in the weeks that followed. “I felt such a calling, I was stopping people on the street.” The photographs were displayed at a well-attended exhibition at a gallery in San Miguel’s historic Fábrica La Aurora art and design space.

After a 2021 COVID hiatus, Van Doren updated the exhibition in 2022. The state government would no longer release a list of the year’s murdered women, but members of Ser Mujer received many names through support groups for families of the disappeared.

The lack of complete information about femicides is a widespread problem. “In my investigations,” noted Van Doren, “I found no reliable tracking system. I also learned that rates of femicide among Indigenous women in the U.S. and Canada are particularly horrifying. That inspired me to open up the project beyond Mexico. This is global.”

According to recent World Bank data, Mexico is among the countries with the highest levels of femicide worldwide, along with El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Venezuela, Central African Republic, South Africa, Jamaica, and Guyana. While falling below the aforementioned countries, the rate is also appalling in the United States. Three women are murdered every day by current or former partners in the U.S., per U.N. data. Around the world, one out of every three women experience physical or sexual violence during their lifetimes. Someone you personally know carries that trauma.

This year, Van Doren found that changing the name of her project from Un día sin mujeres — an homage to the 2020 women’s strike — to the Healing Words Project (Proyecto Palabras Curativas) made people even more receptive to participating. “Words are powerful. People use these words to reclaim what was taken from them. To reclaim themselves.”

Moreover, she noted, participants are creative. One woman this year chose the Ho Oponopono prayer, the Hawaiian prayer of forgiveness toward an aggressor, one of the hardest things a person can do.

As an art therapist, Van Doren believes in process over product. Although everyone wants a beautiful photo in the end, the process is a big part of what’s so powerful about this project. “It’s really about healing. Women need a place to put their trauma.”

In addition, many women brought their young kids and teens to their photo shoots, so conversations about the project began to happen organically with the children. “We had to talk about why we were thinking of empowering words to write on our arms, so we started talking about our basic human need for security and where we can go if we’re scared, who we can talk to,” said Van Doren. “It started becoming an early intervention project around basic human rights, not always about women or men but about what everyone deserves as a human being.”

“Different cultures have different values and different family scripting,” Van Doren continued. “I’ve always been very careful to not say right or wrong but just to listen actively and hold space—and then to ask, ‘Ok, now that we’ve talked about this, what do you want to say?’ And that’s the best part. I see it as pulling the apple from the tree and then taking a bite and consuming it. The person gets to manifest this really powerful part of themselves.”

Van Doren prefers to shoot only one to three people at a time now. It takes longer, but she finds the process more satisfying with more time to get to know the subject.

“We talk about what they’re reclaiming for themselves. And that’s the meat. That’s where the healing happens.”

I encourage residents and visitors to San Miguel de Allende who would like to participate in the Healing Words Project to contact the artist through her website. Participants receive digital images for free, and prints can be ordered from the website.

Based in San Miguel de Allende, Ann Marie Jackson is a writer and NGO leader who previously worked for the U.S. Department of State. Her novel The Broken Hummingbird will be out in October. Ann Marie can be reached through her website, annmariejacksonauthor.com