April is here! For many, this means the sprouting of spring: perhaps some nice, warm rain, maybe picking some wildflowers, or maybe even getting to see a few cute baby animals.

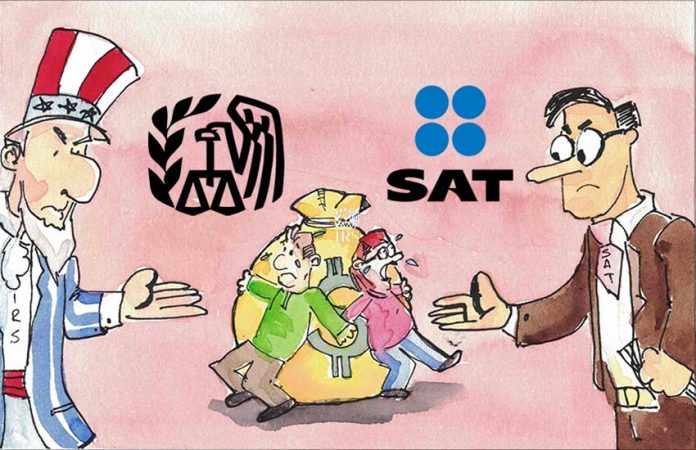

For those of us either from the U.S. — or who happen to have dual citizenship through a U.S. parent, it also means that tax season is once again upon us.

For U.S. citizens, April (or June if you’re out of the country, though you still must pay by April) is the time to file and very likely pay wherever you might happen to be in the world. If you’ve been an immigrant to another country for 50 years, there are, officially, IRS filing requirements.

If you’ve never really stepped foot in the United States but are a citizen by birth — for example, if you were born in the U.S. to parents who left the country shortly thereafter — there are, officially, IRS filing requirements.

The United States is the only country in the world still holding on to citizenship-based taxation (save a small Eastern African country, Eritrea, who asks its own citizens residing outside of the country to pay them a flat 2% tax on their earnings). That grip, unfortunately for those of us trying to build sensible financial lives in our homes outside of the United States, has only strengthened of late.

And with the extraterritorial law FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act), there’s no playing dumb or being “dumb” for that matter: foreign banks are required to report U.S. citizens’ local accounts to the IRS; those banks that refuse to do such reporting simply do not serve anyone with U.S. citizenship.

And for all U.S. citizens, failing to file one’s financials in another country through the FBAR (Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts) can mean extremely heavy fines.

Meant to catch the uber-wealthy and U.S. corporations from stashing cash tax-free oversees, these rules have quite a big negative impact on those of us “regular folk” who live outside of the U.S.

In Mexico — as well as for U.S. expats living around the world — it means that we must deal with two different tax systems: contrary to popular belief, filing and paying taxes to your host country doesn’t mean that you’re off the hook with the U.S.

U.S. tax law does allow some expat taxpayers to take the foreign income exclusion, but not if you’re not a full-time, bona fide resident of Mexico; and if you’re self-employed in Mexico, you can qualify for the exclusion, but the excluded amount will only reduce your regular income tax, not your self-employment tax.

What’s a gringo to do?

According to Fabien Lehagre, president of Association of Accidental Americans and Keith Redmond, founder of American Expatriates for Residency Based Taxation and cofounder of Stop Extraterritorial American Taxation, there’s only one answer that makes sense: stop citizenship-based taxation.

Mr. Lehagre, for his part, is an “accidental American:” though he was born in the US, he has never lived there nor had ties to the country. He and many like him, he says, were not even aware that they were required to file with (and much less pay) the IRS until FATCA came along.

“Imagine the surprise of having to declare your income to the IRS when you have no connection with the United States or even though you left the United States a very long time ago…For accidental Americans, it’s even more Kafkaesque because beyond the fact that many do not even speak English, most did not even know that they had American nationality.”

Examples of this unpleasant situation abound. Says Lehagre: “A business owner, a French citizen born in the United States of two French parents, having left the United States when he was 15 days old and having no connection with the United States, had to, for professional reasons in accordance with the IRS, renounce U.S. citizenship. It cost him over $130,000 in attorney fees and taxes.”

As more and more U.S. citizens move their families to Mexico, it’s easy to see the implications of this for our own children should they decide to stay in Mexico as money-earning adults.

So why is it like this in the first place?

Reasons, of course, are numerous. Lehagre points to the Civil War as a starting point: the US decided that all citizens would need to be taxed to support the war effort, and CBT (citizenship-based taxation) never went away after that.

Redmond adds: “It’s a multidimensional reason…the real question is, why doesn’t the US change to RBT (residency-based taxation) the rest of the world practices?”

For citizens residing outside of the U.S., the consequences of it are quite punitive. Intentionally or not, there are numerous ways in which it restricts many U.S. citizens from accessing financial products to help them save for retirement or invest in both the U.S. (many products are restricted to residents) as well as in their countries of residence.

Another particularly difficult example: the Transition Tax, part of the Tax Cut & Jobs Act (TCJA), a retroactive tax “adversely and ruinously affecting Americans overseas with small to medium sized businesses” who are in the U.S. tax system.

Among those reasons, too, are political ones: “Americans overseas are not a strong voting block, as their votes are diluted across 50 states and territories. Plus, no candidates acknowledge the plight of Americans overseas,” says Redmond. Taxation without representation, indeed.

And who among us immigrants to Mexico haven’t been met with a “that’s what you get” attitude from our fellow citizens? “It is an unusual cultural phenomenon that if one is an American not living in ‘the greatest country in all of mankind,’ one must be hiding money and/or committing some type of nefarious activity,” points out Redmond.

So, what options do U.S. citizens abroad have? As Redmond points out, there are pluses and minuses to any one of them, none of them as perfect as the United States simply ending CBT. These range from “deal with two tax systems and good luck” to renouncing one’s U.S. citizenship or simply choosing to move to the U.S. (whether you’ve lived there before or not).

If you’re like me, none of the choices sound quite fair, which is why lawsuits are currently in the making to fight for residency-based taxation like the rest of the world has (see the link above for the GoFundMe campaign started by Lehagre).

American emigrants face two types of damage, says Redmond. First, there’s the actual damage in terms of financial gains being lost to the U.S. tax system through extraterritorial taxation. Then, there are the opportunities for financial growth that are lost as a result of being outside of the country.

For the growing number of US citizens now permanently living in Mexico, the damage can add up quickly.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com