What was it about Mexico that so captivated some of the renowned dashing, eccentric and artistic Brits of the previous centuries? Mexico had such a magical hold on Frederick Catherwood, Aldous Huxley, Leonora Carrington, Sir Edward James and Fanny Erskine Ingles that they wrote about it, painted it, got deeply involved in society and made it their home.

As a Brit who’s spent the last fifteen years living between New York City and San Miguel de Allende, I’ve often mulled over what kept those who blazed the trail before me, whether they returned home too soon or never at all. Whereas is Britain is known for its reserved and almost uncomfortably polite culture, Mexico, a land of vibrance, color, social turbulence and disparity with a rich history, festivities, desert, dust and cacti is almost diametrically opposed in its flavor.

A very British love affair with Mexico

I can relate to those of my countrymen who developed a love affair with Mexico. Not only have I read some of their books, adored their paintings and heard some intriguing tales about their lives, but some of my own encounters with the people and culture of Mexico have echoed their passion for the country. It was in Mexico that I found freedom, warmth and creativity; that I performed theater, joined a circus trapeze school, danced ecstatically in the street in one of their many festivities and holiday celebrations, hiked in the desert and met strange looking animals and plants.

I was captured by the importance Mexicans place on family; met other wandering explorers from all over the world; participated in centuries-old healing ceremonies and fell in love with the dramatic sweep of the landscape, the sight of three generations that gather in the town square at night, the expressiveness of the language, the taco and coconut water stands by the side of the road, the roaming dogs and cats and the flamboyant clothing, which inspired me to design my own. I even became fond of the incessant fireworks at dawn and the yells and bells of the elote and horchata vendors.

Some of my best friends are Mexicans. They take life in their stride, bemused by the neurotic mindset of Americans or the reserve of the English. They know how to love, laugh and live to the fullest. And, well, they love a good party. But for the adventurous Brits – and there’s a history of them – Mexico welcomes them with open arms, perhaps appreciating their curiosity, and sense of humor.

But who exactly were these people who settled in this exotic land, so far from the sunlit uplands of home?

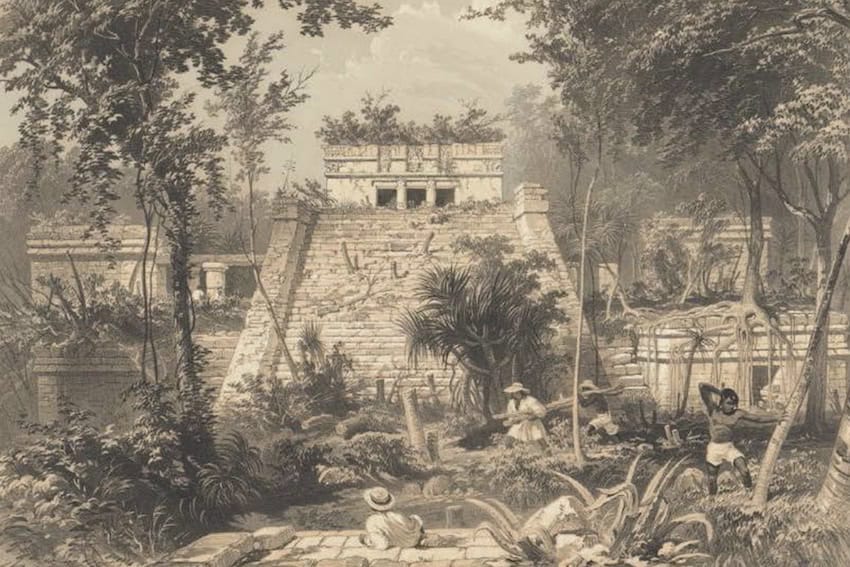

Frederick Catherwood

This early 19th century English artist, architect and explorer discovered the Mayan universe and rendered meticulously detailed snapshots of the ruins of their civilisation, using the camera lucida drawing technique. All the mysterious glory of the previously unknown Maya mesmerized a Europe deep in an obsession with Egyptology, and rocketed Mexican history to the forefront. His books, with John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán and Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, were best sellers. In 1837, Catherwood was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Honorary member.

While the Maya cities of today are celebrated and restored, Catherwood’s work captures an important part of Mexican history at a time when so much of it was thought to be lost.

Sir Edward James

Sir Edward James probably had the most trappings of class and culture of all our British eccentrics in his journey from wealthy aristocrat to the architect of a surrealist castle in the lush rainforest of Xilitla, San Luis Potosí. James was born into a life of privilege at the turn of the 20th century, staggeringly rich and reputed to be the illegitimate son of King Edward VII. His sensitive nature and fantastical way of seeing the world meant he didn’t get far in formal education and the traditional life of the aristocracy in Britain. He soon veered off into the arts, making friends with the likes of Salvador Dalí and stepping into his lifelong role as a patron of the arts.

When James came to Mexico in the 1930s, he fell in love – like so many visitors do – with its vibrance, culture and scale. In the bright humidity of the Huasteca Potosina, he began to construct a home that over the years would become a beacon for artists and thinkers, a place strange and wild enough to house his own free spirit.

He would walk among the rock pools and bathe naked in the waterfalls, deciding whether or not he had the forest’s blessing to visit which pools depending on whether a flutter of butterflies gathered around him. On one such occasion, he was washing his hair when he saw what looked like a troupe of penguins coming towards him. Rubbing the suds from his eyes, the penguins dissolved into a line of nuns from the local church. Embarrassed, he asked how he could help and upon hearing they needed a clinic for the poor, he promised to build it right away if they would only give him a minute to get dressed.

Edward James loved his surroundings and worked with local artisans to bring his singular vision to life. The concrete staircases to nowhere and doors standing like portals to the infinite blend spectacularly into the tropical greenery of Las Pozas, drawing in visitors from all around the world.

Leonora Carrington

Anyone who has stared intently at a Leonora Carrington sculpture and felt the otherworldly creature stare back, recognizes the power and sheer strangeness of her work. The playful composition of Carrington’s “Cocodrilos,” passed by millions each year along Mexico City’s Paseo de la Reforma, gives the impression it has floated straight out of a book of fairy tales. Like so much of her work though, it could just have easily loomed up from the underworld.

Carrington fled war-torn Europe in the 1940s and established a life for herself in Mexico — like her good friend Edward James — far from her aristocratic upbringing. Her struggles with mental health and time spent watching a continent on the edge of darkness ensured her dreamscapes were never simply an escape from reality, but contained within them its totality, grim omens and all. Carrington lived most of her life in Mexico City, producing prolifically, weaving folk art and indigenous mythologies into her own personal cosmovision. Her home in Roma Norte still contains original pieces, and while the house is currently closed to the public, Carrington’s work can be seen throughout the country in her public sculptures and paintings exhibited in museums.

Currently, the best place to see a collection of her work in Mexico is the state of San Luis Potosí. Both San Luis city and the town of Xilitla have permanent Leonora Carrington museums that house her paintings, illustrations, textiles, etchings and jewelry. Walking around Xilitla, you simply have to look out over the rooftops to see her sculptures peeking back at you.

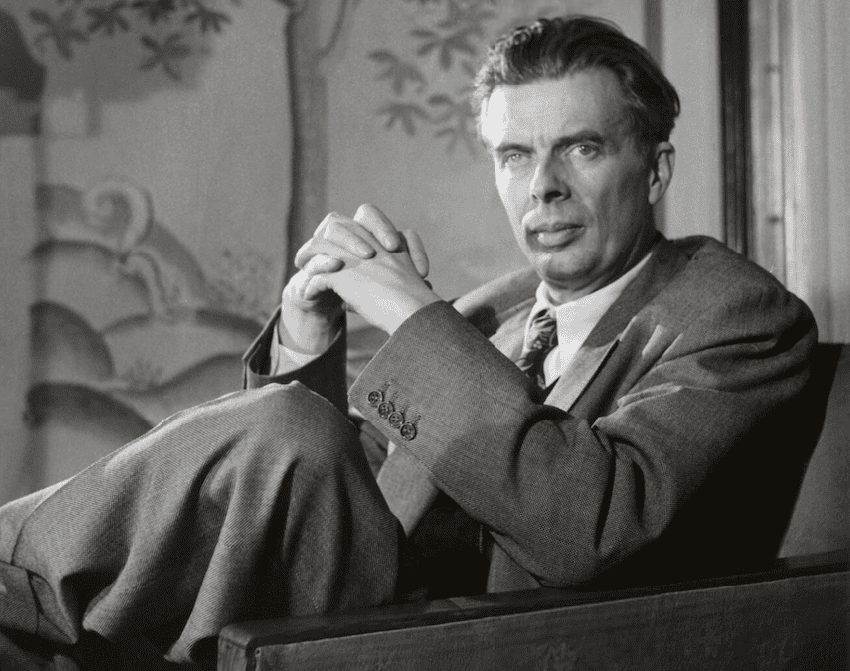

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley, the cerebral English author and philosopher, found new ways of looking at the world wherever he chose to direct his attention. Having begun his writing career as a keen social satirist of the British class system, he came to Mexico in the early 1950s, seeking an environment where he could explore the grander ideas of consciousness and mysticism.

Huxley’s journeys through southern Mexico, captured in the book of essays “Beyond the Mexique Bay,” gifted him with a rich cultural and ethnobotanical context for his later journeys into altered states of consciousness.

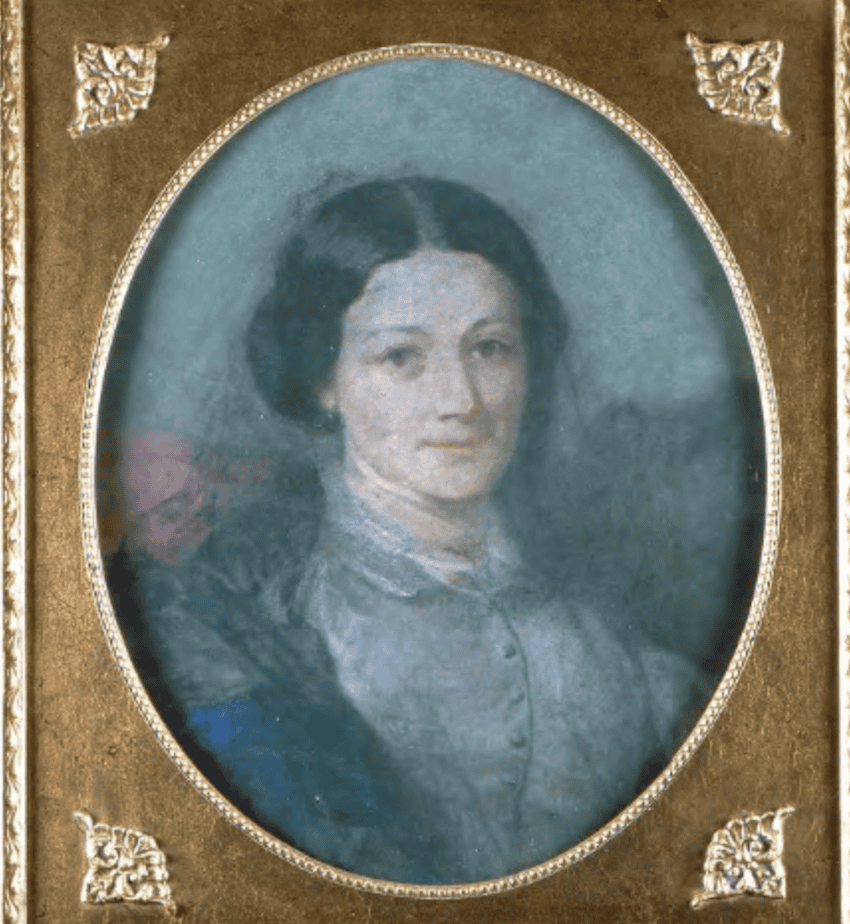

Frances Erskine Inglis, 1st Marquise of Calderón de la Barca

Fanny, as she was familiarly known, was the ultimate upper-echelon Scottish lady adventurer. As the charming young wife of the Spanish plenipotentiary envoy come to negotiate Spain’s recognition of Mexican independence, she had unrestricted access everywhere and anywhere in Mexico. Very well endowed by nature and fortune, she was reportedly bright, beautiful and talented. As heiress to Scotland’s largest brewing fortune, Fanny was also extremely wealthy.

Fanny wrote the ultimate travel narrative of the 19th century, “Life in Mexico,” published under the name Madame Calderón de la Barca in Boston and London in 1843. Her observations and insights are so alluring that she is rumored to have become a principal intelligence source for the United States’ invasion of Mexico in 1847.

Truth to tell, as I talked to some of my British friends who have lived and worked in Mexico for years, I unearthed many more fascinating Brits who chose to flee to these southern latitudes and made quite a dent.

The stories of the English novelists D.H Lawrence and Graham Greene and the Irish (who was then British) freedom fighter William Lamport — who inspired the legend of Zorro and actually crafted one of the first plans for Mexican independence — are scintillating tales for later this month. I always like to end on a cliffhanger; just like any Brit that’s adventured to — and got hooked on – Mexico!

Henrietta Weekes is a writer, editor, actor and narrator. She divides her time between San Miguel de Allende, New York and Oxford, UK.

To read more in the Global Mexico: UK in Focus series, click here.