María Antonieta Rivas Mercado, who killed herself in Paris’ Notre Dame a few weeks before her 31st birthday, may be best remembered by the world for her immortalization in Diego Rivera’s Mexico City mural, “El que Quiera Comer que Trabaje” (“He Who Wants to Eat Must Work”), but in Mexico, she’s known as one of the most influential figures on Mexico’s cultural institutions during Mexico’s postrevolutionary era.

Born on April 28, 1900, Rivas Mercado, the second daughter of renowned architect Antonio Rivas Mercado — creator of Mexico City’s iconic monument, the Ángel de la Independencia — grew up in what is now the Casa Rivas Mercado museum in downtown Mexico City. She had a romantic childhood surrounded by arts and culture.

An avid reader and fluent in French and English, she had access to an education that few women did at the time, learning piano and history from private governesses. At 3 years old, she wrote a love poem to her father.

Antonio was a central figure in his daughter’s life, since Antonieta’s mother, Matilde, who had European blood and features, often ignored her due to the girl’s indigenous appearance. In a story told in the best-selling book “In the Shadow of the Angel“ — written by Kathryn Blair (the wife of Antonieta’s only child, Donaldo) — Matilde asks Antonio soon after their daughter is born: “Don’t you think she’s too brown?”

Matilde had German and indigenous heritage, but she, as did the rest of her children, had European features.

But Antonio admired and cultivated the girl’s bright and curious mind. In 1909, she and her older sister Alicia traveled with him to Paris to supervise the ornamental details for the Ángel de la Independencia, which was to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Mexico’s independence.

While in Paris, Antonio took Alicia and Antonieta on weekly visits to the Louvre, where Antonieta learned the value of art.

“The primal function of art is to create beauty,” Antonio would tell his daughters.

He also took them to the theater and to the Paris Opera, where they once watched a ballet performance. Young Antonieta fell in love with the art and was later admitted to the ballet school of Monsieur Soria, where she was considered a gifted young dancer. However, after a year, Antonio took her daughters back to Mexico despite Antonieta’s wishes.

On September 16, 1910, the Ángel de la Independencia on Paseo de la Reforma was inaugurated in a magnificent event, but a revolution was brewing both in Antonieta’s home and throughout the country: Rivas’ mother decided to leave her family, and the Mexican Revolution began.

The Revolution (1910—1917) marked Rivas’ life: She witnessed violence, death, hunger and the abuse of power. In February 1913, Mexico City was violently occupied for 10 days as Álvaro Obregón’s forces attempted to oust President Ignacio I. Madero.

During this time, she was a prisoner in her own house along with her father and siblings. In her book, Kathryn Blair describes how the Rivas Mercado family suffered food shortages just like any other peasant in the country.

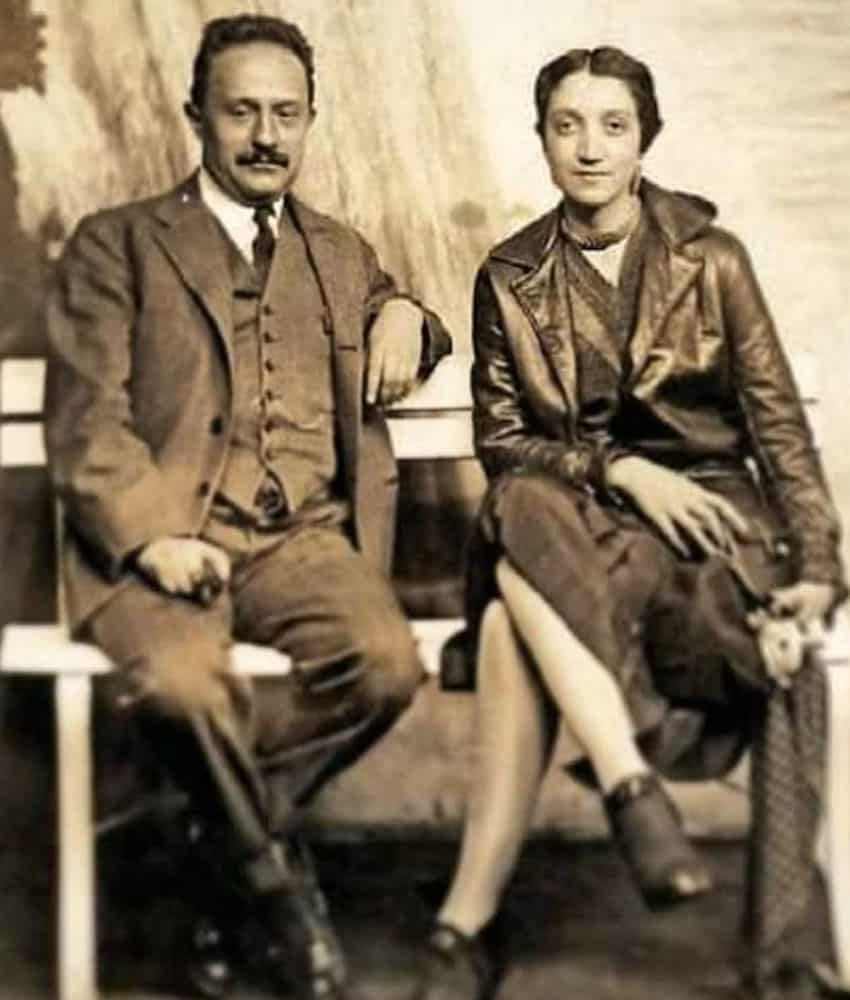

After the Revolution’s end, Rivas, now aged 18, married Albert Blair, a British man who had fought in the Mexican Revolution. The pair had only one son, Donald Antonio Blair.

However, the relationship was not meant to last: her husband felt that Rivas’ reading material fed her brain with strange ideas and romantic illusions. He forbade Rivas to speak to their son in French and burned all her favorite books from authors like Nietzsche, Verlaine, Baudelaire and Proust.

She eventually became one of the first women in Mexico City’s elite to ask her husband for a divorce. Furious, Albert threatened to deprive her of custody of Donald, resulting in a long court battle.

But she ultimately regained her independence and moved back to her childhood home, where she devoted herself again to her interests. When her father died in 1927, she used the fortune she inherited to finance many cultural projects in Mexico, many that changed its cultural history forever.

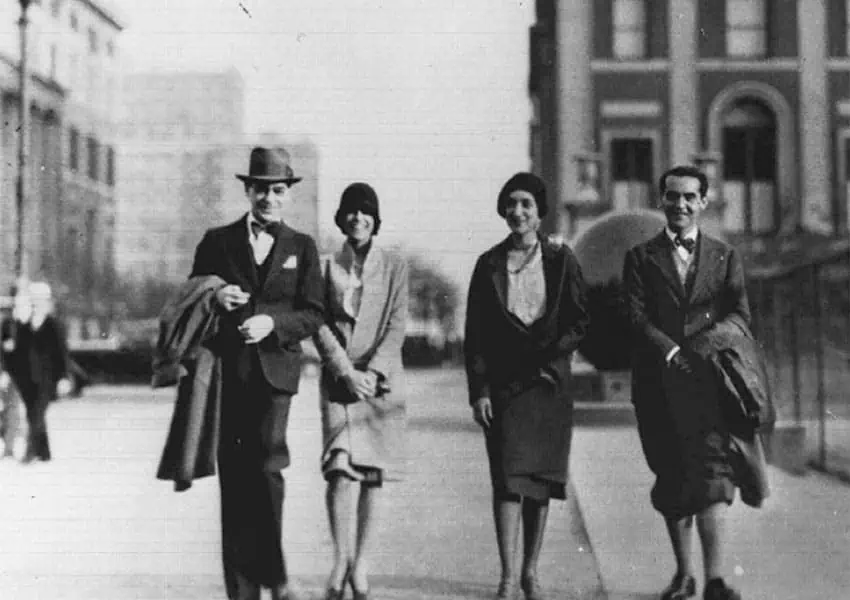

Through her close friendship with painter Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, she met Los Contemporáneos (The Modernists), a group of young Mexican intellectuals who recognized the emergence of an unprecedented universality of cultural expression in which they sought to contribute. Sharing their vision, Rivas not only became their patron but also a member.

She also financed and helped create the experimental Ulises Theater with Los Contemporáneos. Although it only lasted for a few months, it influenced modern Mexican theater fundamentally.

During this time, she was also an editor of notable books in Mexico by authors such as Xavier Villaurrutia, Gilberto Owen and Andrés Henestrosa. She was also the first person to translate to a foreign language (English) the works of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca and scripted the first theatrical adaptation of the novel “Los de Abajo” (Those From Below”) by Mariano Azuela.

She also founded the Mexican Symphony Orchestra in 1928. Together with Mexican composer Carlos Chávez, they created the most important musical ensemble the country had seen to date.

Her concern for women’s rights led her to write several feminist essays. One of those was published in 1928 in the Spanish newspaper El Sol de Madrid.

In “The Mexican Woman,” Rivas said that culture was the only means for women’s salvation and stressed the importance of education to “cultivate women’s minds and teach them to think.”

She also founded the first department of indigenous affairs in the Ministry of Education and later became actively involved in politics by financially supporting the presidential campaign of former Minister of Education José Vasconcelos. They later became romantically involved, a development that was to have a profound impact on her life.

When Vasconcelos lost the presidential race in 1929, Rivas had to leave the country after many vasconcelistas (Vasconcelos supporters) were being chased out by the new government.

Rivas sought refuge in New York with her son, whom she took illegally out of the country; her court case to maintain custody was still ongoing. In New York, she met author Federico García Lorca before moving to Paris, where she spent her remaining days.

Although she maintained a natural poise and elegance given by her education and lineage, Rivas and her son were forced to live in precarious conditions; most of her fortune had gone to her cultural pursuits and patronages.

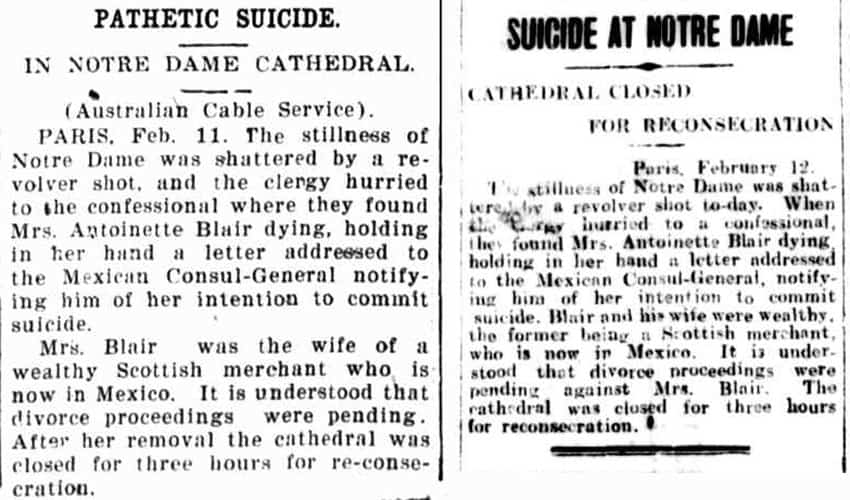

On her last full day of life, she met up with Vasconcelos, after not having seen him in months. The following day, after what she herself termed a troubled life, she shot herself in the heart in Notre Dame Cathedral with a gun she had taken from Vasconcelos’ suitcase the previous night.

In one of her final letters, Rivas wrote to her sister, “Life for me has been suffering and work, the latter my fun and relief. I have never been able to carry a light soul; something has always weighed on me, and in truth, I wish no one such a fate.”

By Mexico News Daily writer Gabriela Solís