A piece of Mexico’s heritage that was about to be auctioned off in Spain six years ago for approximately US $113,000 is on its way back to Mexico.

Although the fragment of the Tlaquiltenango Codex was pulled from the auction by Spain’s Civil Guard in 2017, it took until last month for the Spanish justice system to rule in favor of returning it to Mexico.

“This gesture reinforces the ties between both countries and underlines the shared commitment to the preservation of cultural heritage,” the Mexican government stated in a press release last week.

The return of the piece is another example of Mexico’s commitment to recovering and preventing the illicit trafficking of its cultural property. Thanks to the #MiPatrimonioNoSeVende campaign, more than 13,000 cultural pieces have been recovered from around the world during the administration of President López Obrador.

The latest returned fragment — received Nov. 30 in Spain by Mexican ambassador and former Sinaloa governor Quirino Ordaz Coppel — is part of the Tlaquiltenango Codex, a set of mostly pictographic documents dating from approximately 1525 to 1569.

The documents were painted on amate bark paper and were discovered in 1909 within the walls of the now 430-year-old Ex-Convent of Santo Domingo de Guzmán in Tlaquiltenango, Morelos. In the 1500s, Tlaquiltenango was an important city of the Tlahuica nation, whose capital was Cuauhnahuac (today’s Cuernavaca).

Though the size of the full codex is unknown, it is estimated that there are 345 fragments, of which 207 remain behind the walls of the convent.

The fragment returned by Spain measures 35 cm by 20 cm and is very damaged, although it still vaguely shows what appears to be a list of tributes and exchanges.

These codices were attached “without a pre-established order” to the friezes of the lower cloister of the convent when it was inhabited by Franciscan friars, according to Laura Elena Hinojosa of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH).

Early in the 20th century, “the owner of the land, Juan Reyna, removed them with the help of [an] American archaeologist from the Museum of Natural History in New York,” Hinojosa noted, “and between them they sold almost all the fragments” to that museum.

The Museum of Natural History in New York reportedly has 132 additional fragments, and there are six within the purview of the National Library of Anthropology and History of Mexico.

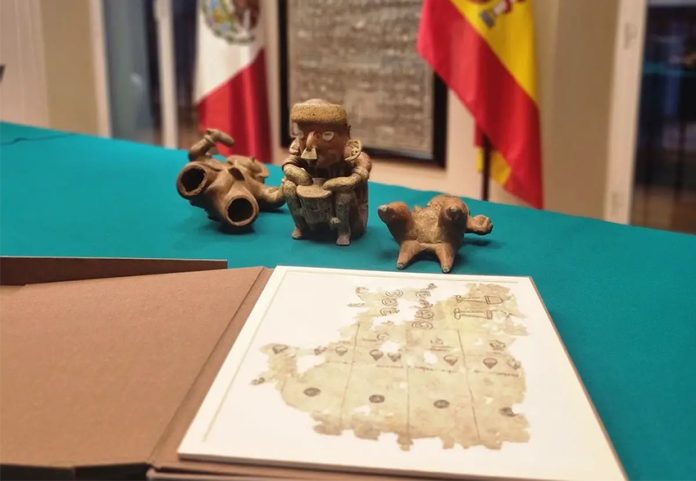

In addition to the codex fragment, Mexico last week also received three archaeological pieces from a Spanish citizen, Carmen Celda, who had them in her private collection. The statuettes are believed to be from the Nayarit area on the Pacific coast.