Over the past year, there have been articles in many publications (including this one) essentially blaming the presence of foreigners for driving up rents in the Roma and Condesa neighborhoods of Mexico City, pointing to the influx of digital nomads and Airbnb rental units.

In media outlets like the New York Times and Al Jazeera one repeatedly finds a narrative of rich foreigners driving out poor people from homes they’ve been in for decades and/or generations.

But Mexico City is not alone in struggling with the issues of gentrification and the overall lack of space, especially in more desirable neighborhoods. And such narratives don’t take into account that neither the historic center, nor the developments just west of it, Roma, Condesa, Juárez and Polanco, were ever established for the poor or even the middle class.

Mexico City’s historic center was founded by the Spanish colonists, literally on top of Tenochtitlán, as land for the conquerors, with most of the indigenous pushed out. The four aforementioned neighborhoods were established over the past 120 years or so as Mexico’s elite looked to escape the noisy, crowded downtown to places that were more exclusive, modern and fashionable.

All were developments on former haciendas, most of them on some of the vast holdings of the Countess (Condesa) of Miravalle, who is immortalized in the naming of Colonia Condesa.

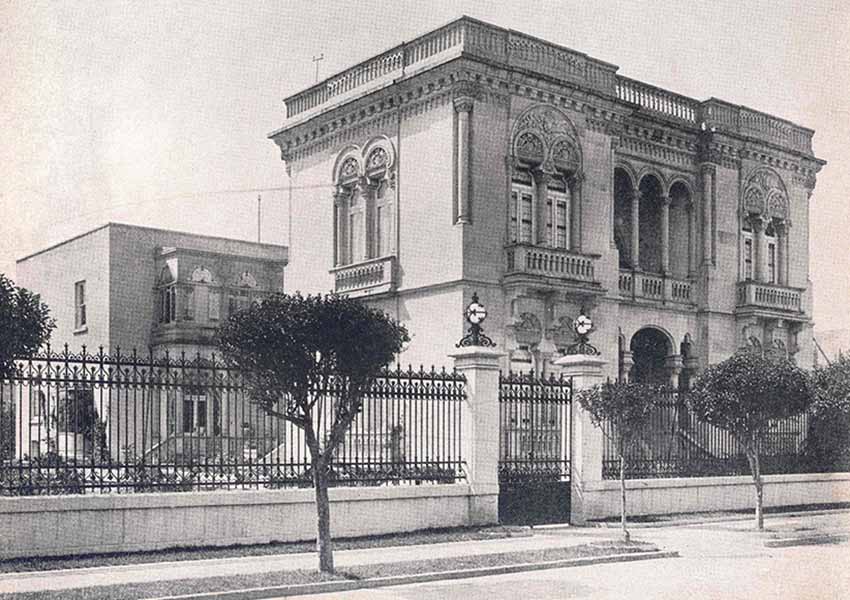

Roma and Júarez were the earliest, developed in the years before the Mexican Revolution, when both the elite and the government were looking to prove that Mexico could be modern by adopting technologies and styles from Europe.

This can be seen in the sumptuous mansions and street layouts, which broke with the strict grid pattern that dominates most of the city today. Roma and Condesa especially are marked by curved and diagonal streets and wide boulevards with tree-filled islands and large parks.

The Mexican Revolution stopped such construction for over a decade, but when it was over, families of the winning factions sought to move to these fancy neighborhoods to show that they had “made it.”

The creation of these neighborhoods started a trek westwards for Mexico City’s elite, which continues to this day, to the edge of the city proper and beyond.

All of the older neighborhoods have experienced downturns with redevelopment, but some have seen more change than others: Juárez and northern Roma (known as Roma Norte) have seen significant commercial redevelopment. Condesa has managed to keep most of its original residential feel.

Roma overall remains the textbook example of the ups and downs of this west-central section of the city because it has experienced all of the relevant economic, social and geological forces.

Walking around, it is easy to see the original boulevards and parks as well as over 1,500 now historic landmarks bearing witness to the wealth and fashion of the very early 20th century. (Condesa and Polanco were established afterwards, reflecting the Art Deco and later architectural styles.)

In the 1960s and 1970s, the construction of the first Metro subway line, along with major traffic thoroughfares, brought commercial construction — and large numbers of the working class and street vendors, just the thing that rich families had sought to escape in the old historic center.

The major breaking point was the 1985 earthquake, which hit these neighborhoods hard, especially the historic center and Roma. In the aftermath, many owners sold or rented damaged buildings or even abandoned them altogether.

But as memories of the earthquake faded, gentrification began: slowly in some areas, faster in others. There was heavy criticism beginning in the 2000s over the conversion of old mansions into commercial buildings.

Residential redevelopment came a little later, as young upper class Mexican professionals were attracted to homes located in neighborhoods with established personalities.

“These structures cannot be duplicated, and they have a premium,” said Andrés Sañudo of the specialty redevelopment company ReUrbano.

So why do foreigners congregate in Roma and Condesa? One basic reason is the uniqueness of the neighborhoods, which have a familiarity to them. The layout of the streets, the quantity of trees and the lack of hustle and bustle of the rest of the city is attractive to those from similar environments outside Mexico.

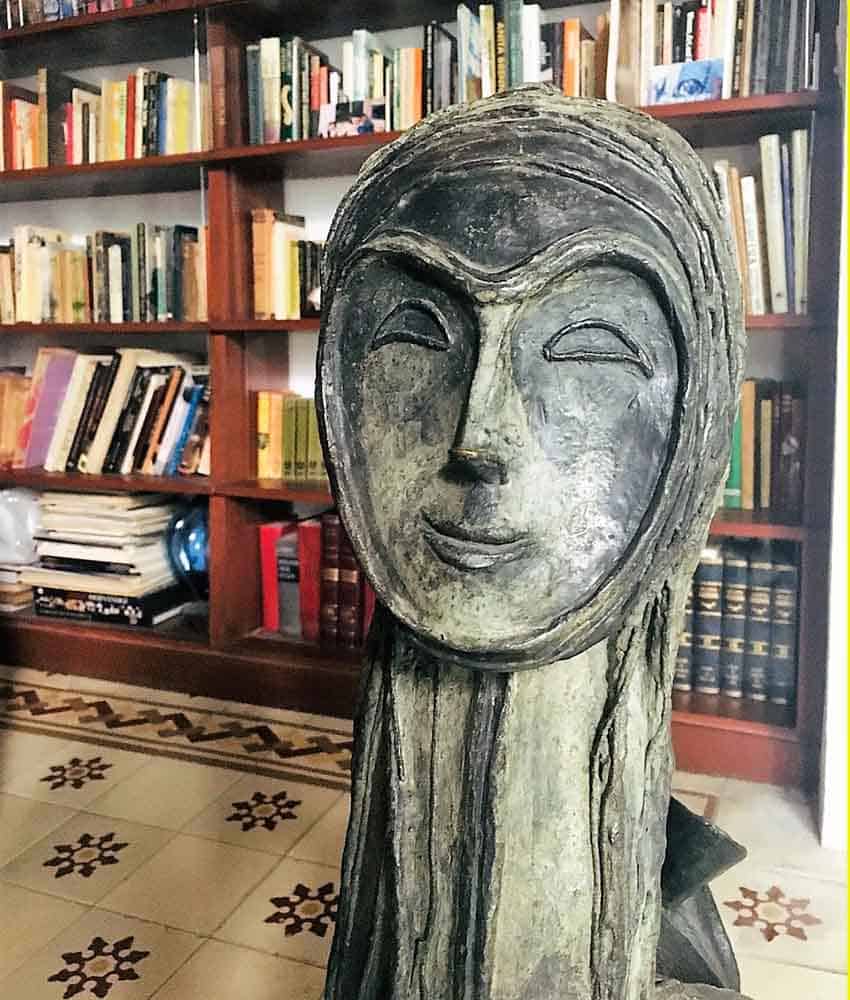

Roma and Condesa’s ambience also reflects that it has been the home of foreigners for many decades. European and American writers, intellectuals and artists found their way here, first because of the famous Mexican muralism movement, then because of an influx of refugees from the Spanish Civil War and World War II.

Names like Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo helped give Roma its current artistic and cultural reputation. The influx of foreigners brought in ethnic restaurants, alternative houses of worship and ethnic cultural centers.

Both elements give newly arriving foreigners from North America and Europe the sense that they are in a “safe” area, important given Mexico City’s general reputation. Unsurprisingly, these immigrants, like those the world over, look to live in areas that give them some sense of familiarity.

Poland-born Edyta Norejko of ForHouse Realty works in Mexico City and concedes that gentrification causes problems that the city should address, but the gentrification process here is driven by economic factors in Mexico City, one being the return of young affluent Mexicans who are attracted to the neighborhoods for many of the same reasons, and who have eschewed the commuter culture of their parents.

For both Mexicans and foreigners, Roma and Condesa will remain prime real estate for the foreseeable future, and will reflect a mix of both local and international influences.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.