In every major Mexican city, there’s at least one building whose walls burst with color, waiting for you to explore them. But beyond their impressive scale, what truly makes each mural remarkable is the commitment the Muralist movement shared with the Mexican Revolution.

Murals weren’t made just for aesthetics; they were a tool in a country where nearly 90% of the population couldn’t read or write. Today, those numbers have changed, but the purpose of muralism remains: to showcase historical events whilst expressing the artists’ visions of the nation’s future.

Even though it’s been a while since muralism saw its golden days, these massive pieces of artwork continue to captivate locals and foreigners alike, creating a strong bond between art and national identity. What’s portrayed in the murals is meant to be remembered as history — at least, one version of it.

First, let’s talk about the Revolution

The Mexican Revolution was a movement that exposed the urgent necessities of a marginalized population, tired of an authoritarian government represented by dictator Porfirio Díaz and his three-decade regime. When the majority of the Mexican population realized that just a few could live a dream life, while the others literally starved, revolutionary ideas started shaping what became an armed movement.

Although the beginning of the confrontation served as a catharsis for the population, the latter part of the war evolved into an internal dispute over who should be in charge once the war ended. And so, the battles were guided more by politics and less by the possibility of a better life.

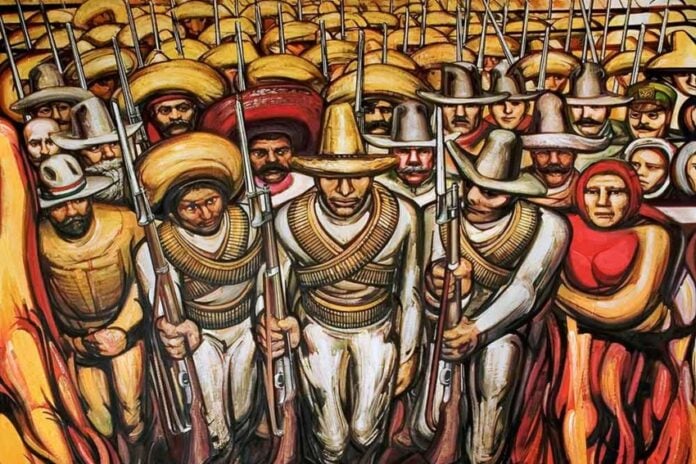

However, confrontation between those in power and those who worked the land had a specific flavor, as it became the first Revolution of the 20th Century. The Mexican Revolution was also the first led by the working class, which deeply inspired the motifs on which muralism is based.

The Big Three: Siqueiros, Rivera and Orozco

At the same time that Diego Rivera was holding his first solo show after returning from Europe, David Alfaro Siqueiros was on the battlefield, and José Clemente Orozco was in the trenches of Veracruz, listening to revolutionary speeches by Dr. Atl. One thing was certain: the three of them were forging their inner artists to become Los tres grandes — the “Big Three.”

When visiting the Palacio de Bellas Artes, you’ll find yourself surrounded by their creations. But even in that shared space, you won’t feel the same standing before Siqueiros’ “Tormento de Cuauhtémoc” or Rivera’s “El hombre controlador del Universo.” And both feelings differ, of course, from the one you get when staring at Orozco’s “Katharsis.” Siqueiros overwhelms you with intensity, violence and movement; Rivera invites reflection through order, symbolism and balance; Orozco’s chaotic energy and cartoonish characters laugh at everything — and everyone.

Diego Rivera

Even though Rivera presented himself as a revolutionary man, there was a part of him that was a little bit of an outsider. He never really knew what being on the battlefield meant (like Siqueiros and Orozco did). Yet, he had the opportunity to experience art as few artists can: on a scholarship before World War I took its toll on Europe.

Diego tried every technique and met every (or almost every) renowned name of the time. From his long-lasting friendship with Pablo Picasso to his brief but intense marital life with painter Angelina Beloff, he was learning everything he could from the Old World to bring it back home … and so he did.

David Alfaro Siqueiros

Siqueiros’ nickname “El Coronelazo” didn’t come easy. The muralist left the Academia de San Carlos — the only art academy in Mexico at the time — to join the revolutionary army. As a teenager, Siqueiros was already a soldier, fighting for the causes he believed in —a characteristic that led to his later participation in the Spanish Civil War and the student movement of 1968.

After the war was over, David Alfaro Siqueiros changed the gun for a paintbrush. Besides being one of the founders of the muralist movement, he was also a precursor in experimenting with 3D paintings, introducing the use of pyroxilyn on walls and canvases.

José Clemente Orozco

The connection Orozco had with the Revolution grew as he learned from his teacher, Dr. Atl. During the war, both were part of La Vanguardia, a newspaper that pursued revolutionary causes, like “building the Revolution” through text and pictures.

Orozco recalls Dr. Atl’s lessons: “We had to learn from the old masters and from foreigners, but we could do as much, or even more, than they did. Not out of pride, but out of confidence in ourselves, an awareness of our own being and of our destiny.”

Unlike his two partners, Orozco’s art represented not reality in its most literal form, but a satiric and always critical version of it. As he did at La Vanguardia, the characters of his murals showed their worst traits. That is the main reason he is sometimes left behind. Whereas Siqueiros and Rivera capture the essence of the Revolution, Orozco criticizes the whos and the hows, filling his pieces with discomfort.

There’s no trinity without a godfather

To understand muralism, we must return to the moment of its birth. The Mexican Revolution had ended, but the struggle for food, shelter and national identity continued. What did it mean to be Mexican?

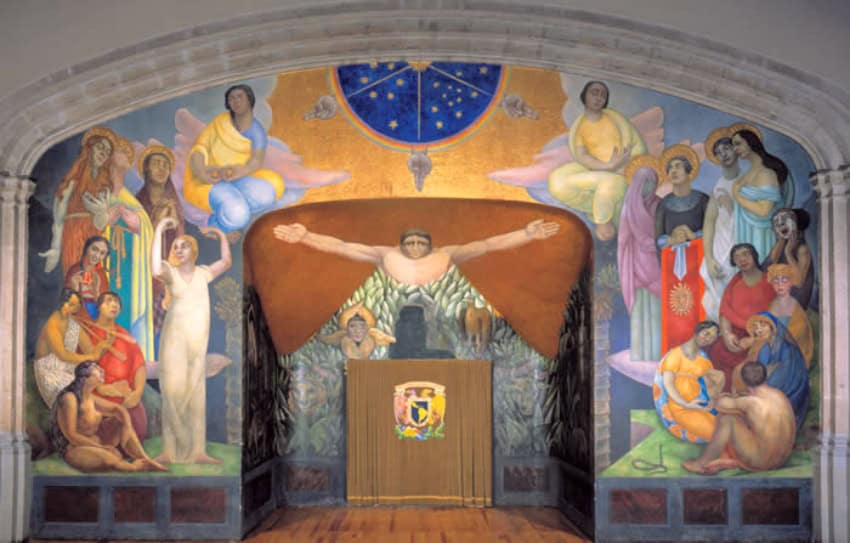

With the intention of answering that question, the newly appointed Secretary of Education, José Vasconcelos, created a movement that could do both: create an identity for the re-established nation and produce works of art to show the world what Mexico had to offer. It all began with the buildings under his authority: Escuela Nacional Preparatoria and Secretaría de Educación Pública.

It has been said that Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, located in the colonial building that once served as Colegio de San Ildefonso, is the cradle of muralism, and those who say so are not wrong. The halls and corridors that hosted high school alumni also witnessed Dr. Atl’s first experiments on muralism, a task interrupted by the Revolution.

Reimagining Mexico’s history

Once the war ended in 1922, Vasconcelos hired 35-year-old Diego Rivera to paint “La Creación,” inside the school’s amphitheater, a symbolic piece that portrays Adam and Eve and the creation of something new. It was related to the beginning of Diego’s muralist career, but also with the whole movement — something was about to happen at San Ildefonso and the world would be stunned by it.

This historical place preserves in its walls the works of young muralists such as Jean Charlot, Fernando Leal, Ramón Alva de la Canal and Fermín Revueltas. Orozco was also invited to this muralist assembly, of course. The murals displayed scenes of Mexico’s history, from Hernán Cortés to current local celebrations. These paintings depicted every color in the country’s light prism.

On the other hand, Diego was also commissioned to design two government buildings: Secretaría de Educación Pública and Palacio Nacional. The first held the national offices of the Ministry of Education, the second was the headquarters of the Mexican presidency. While the murals in both buildings were inspired by social and political events, Secretaría de Educación Pública’s (S.E.P.) artwork shows a deeper representation of the ongoing revolutionary process of the country.

Rivera shows us what the soldiers were fighting for, trying to share their history with every visitor of the S.E.P. It is no coincidence that in one of the most intense panels, Rivera painted portraits of three artists delivering weapons to the working-class fighters: fellow muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, photographer Tina Modotti and a young, revolutionary Frida Kahlo, who would later become his life-long partner.

Before and after the ‘Big Three’

In contrast to Italian muralism, which reached its peak with Michelangelo’s “Sistine Chapel,” Mexican muralism stems from something deeper, something rooted in Mesoamerican cultures. Think of the wall paintings at Bonampak or the magnificent frescoes in Teotihuacán. Even the now-bare Templo Mayor was once covered in color during its golden age.

Muralism wasn’t created; it was rediscovered, not only in format but in its technique. Muralists moved from European encaustics to the traditional fresco used by Mesoamerican artists for millennia.

As poet Octavio Paz wrote in “Los Privilegios de la Vista,” the Revolution created the perfect opportunity to reflect on what the century-old nation had done right and what path it should follow toward the so-called “civilized world.”

“Our painting is a chapter of modern art. But at the same time, it is the expression of a people who have just discovered themselves and who, not content with recognizing themselves in their past, seek a historical project that will place them within contemporary civilization.”

Although muralism, as the movement led by Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco, no longer exists, the walls still call for color, and artists continue to answer. From the murals painted along the U.S. border to the marvelous rótulos that accompany street vendors, muralism remains.

Lydia Leija is a linguist, journalist, and visual storyteller. She has directed three feature films, and her audiovisual work has been featured in national and international media. She’s been part of National Geographic, Muy Interesante, and Cosmopolitan.