Tax time in Mexico is coming, and more than a few of us foreign residents make our annual declarations between February and April. It is also the time that Mexican artists can take advantage of Mexico’s one-of-a-kind payment program for creators.

Called Pago en Especie (payment in kind), it is a barter system where works of art can be substituted for cash tax payments.

The scheme was the brainchild of famous muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. In 1947, the federal government began to require artists to pay taxes on their income and sales. Although post-Revolution greats such as Siqueiros and Diego Rivera would be exempt for the rest of their lives, they were concerned about this new burden on younger artists to whom they were passing the baton.

In 1957, Siqueiros and other notable artists petitioned the government on their behalf. They convinced authorities to allow notable artists to “pay” their taxes by “donating” one artwork to the government for every five paintings sold.

For the aging muralists, it was a case of self-serving altruism. The arrangement not only helped to keep their movement alive but fit with their ideals, providing a “socialist” alternative for Mexican artwork in the face of a growing private market. The deal also included building a museum to house and promote the new public collection, but that would not happen until 1994.

Instead, when the Modern Art Museum (Museo de Arte Moderno) opened in 1964, the collection became a cornerstone of its work. Three decades later, the federal tax agency (SHCP) would finally open the Art Museum of the Secretariat of Finance and Public Credit.

One of the initial purposes of the program was to conserve muralism as Mexico’s dominant visual art form, and younger Mexican artists inspired by international trends in the mid-20th century had difficulty getting their work accepted. Eventually, however, this so-called “Breakaway Generation” succeeded in expanding the range of works the collection would accept.

The basis of the program has remained the same over the decades, but its details have been tweaked various times. Initially, the program was quite generous, allowing artists to determine which works would count as payment. That began to tighten significantly with the death of the last great muralist, Rufino Tamayo, in 1991. The SHCP instituted a committee to accept artists and works into the program. In 2022 the agency switched to a system of valuation by certified appraisers instead.

The program was initially focused exclusively on the classic plastic arts – painting, sculpture, photography and prints in particular, but over time it began to accept installations and digital art as well. A more significant conceptual change occurred in 2017 when the SCHP began to accept works by nationally recognized artisans and folk artists.

The result is one of the largest collections of modern and contemporary art in Mexico with over 5,000 pieces. It is not Mexico’s only federally-managed art collection, but its history means that it is managed separately from those related to the Culture Ministry. The SCHP museum is located at the former Archbishop’s Palace in downtown Mexico City, but the collection is so large that parts of it are on permanent loan to other institutions. The purpose of the collection is exhibition within the country and such exhibitions appear regularly at museums all over Mexico.

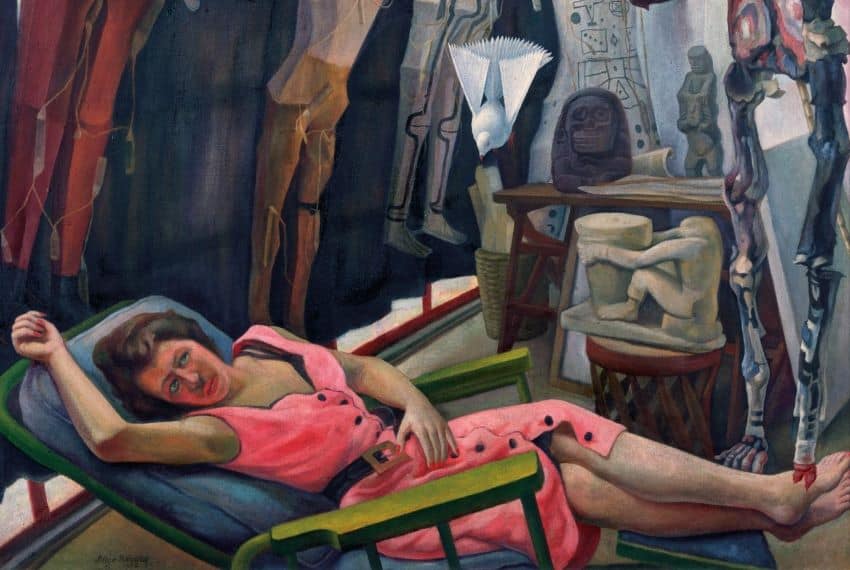

The collection covers Mexico’s major art movements from the muralism period to the present. It contains works by famous names such as Rufino Tamayo, Mariana Yampolsky, Vicente Rojo, Manuel Felguérez and José Luis Cuevas along with those of up-and-coming artists such as Verónica Villarreal, Manuel Carrillo Lara and Manuel Armando Solano Lozano.

The program is open to both Mexican and foreign resident artists, but applicants must be accepted by SHCP, and even then the agency will accept only works that are properly authenticated. Last, but not least, the artist needs to register with the tax system (and have no outstanding debts).

The SCHP says that the program is the only one of its type in the world, but there have been criticisms. One early objection is that the program skews the private market. Another common complaint is that most of the works are in storage, managed by bureaucrats and of questionable public value. The most common criticism has been that this tax option has not been extended to other types of artists, most notably those in the performing arts, leading to accusations that plastic artists “evade” taxes.

However, the program remains an important resource for more than a few artists in the country. Cecilia Santacruz, general coordinator of the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana (Mexican Hall of Arts) says that over 150 members have participated and that acceptance onto the scheme remains an important part of these recognized artists’ trajectories “…not only thanks to the economic support that Pago en Especie provides, but also the promotion of new markets for art.”

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.