The story of Joaquín Murrieta — the legendary Mexican Robin Hood who inspired the story of El Zorro — has endured and evolved over almost 200 years. To the American authorities in California during the Gold Rush, he was a notorious criminal, but to Mexicans, he was El Patrio: the patriotic avenger who came to symbolize defiance of U.S. oppression.

The facts of Murrieta’s life are elusive, but the story really begins with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, between the United States and Mexico. The terms which ended the Mexican-American war forced Mexico to cede more than 50% of its territory — including the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah and New Mexico; most of Arizona and Colorado; and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming.

That same year, Murrieta, at age 18, migrated from Sonora, Mexico, to California with his wife, brothers and three of his brothers-in-law to prospect for gold during the California Gold Rush. By all accounts, Murrieta was a successful forty-niner, but as a Mexican, he suffered persecution and discrimination.

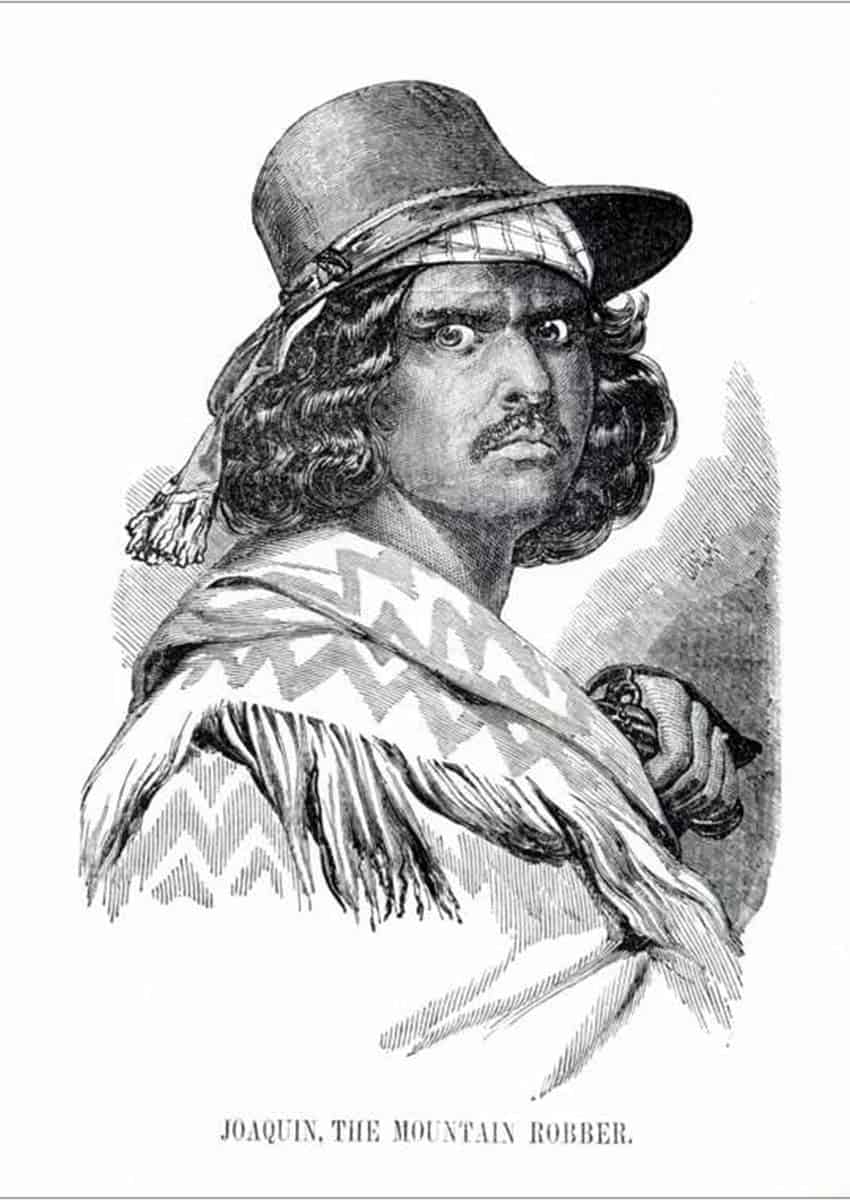

Cherokee novelist John Rollin Ridge (Yellow Bird), who wrote “The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit” in 1854, says an assault in 1849 changed Murrieta from a peaceful miner into an outlaw.

Murrieta and his family were attacked by a group of U.S. miners who stole his land and home, hanged his brother for a crime he didn’t commit, horse-whipped Murrieta and raped and murdered his young wife.

At the time, authorities in California were engaged in efforts to expel Mexicans from California and turned a blind eye to such attacks.

Murrieta complained to the authorities, Ridge says, but only suffered more outrage and so decided to avenge his family himself. He vowed to kill every “Yankee” he encountered.

He and accomplice Manuel García, who was known as “Three-Fingered Jack,” formed a gang: The Five Joaquíns, consisting of Murrieta and four other members all named Joaquín. García functioned as Murrieta’s right-hand man.

They quickly moved from horse theft to assaults, robberies and murder. It is said that in the next few years, they stole more than US $100,000 in gold and 100 horses and killed more than 19 men, including those who had attacked his family.

After robbing their victims, it was said that Murrieta’s gang would distribute the gold they stole among the poor. The legend of this Mexican Robin Hood grew as more and more stories circulated about Murrieta giving stolen gold to those who needed it most. It made him popular with Mexicans but a dangerous threat to the American authorities.

In 1853, California Governor John Bigler decided to put an end to Murrieta and his gang. An 1853 bill passed in the state legislature labeled The Five Joaquíns criminals and authorized the hiring of 20 California Rangers — all veterans of the Mexican-American War — to track them down. Bigler also put a bounty on Murrieta’s head to incentivize people to turn him in.

No one did.

The Rangers were led by Captain Harry Love, who was credited with Murrieta’s eventual capture. For months, the Rangers searched for Murrieta and his gang, suspecting that due to Murrieta’s hero status, Mexican families were helping him elude the authorities.

The Rangers finally encountered a gang of armed Mexicans near Arroyo de Cantua, and in the gunfight killed three of them, including Murrieta and Three Fingered Jack. A California historical landmark plaque now marks the site where Love claimed Murrieta was killed.

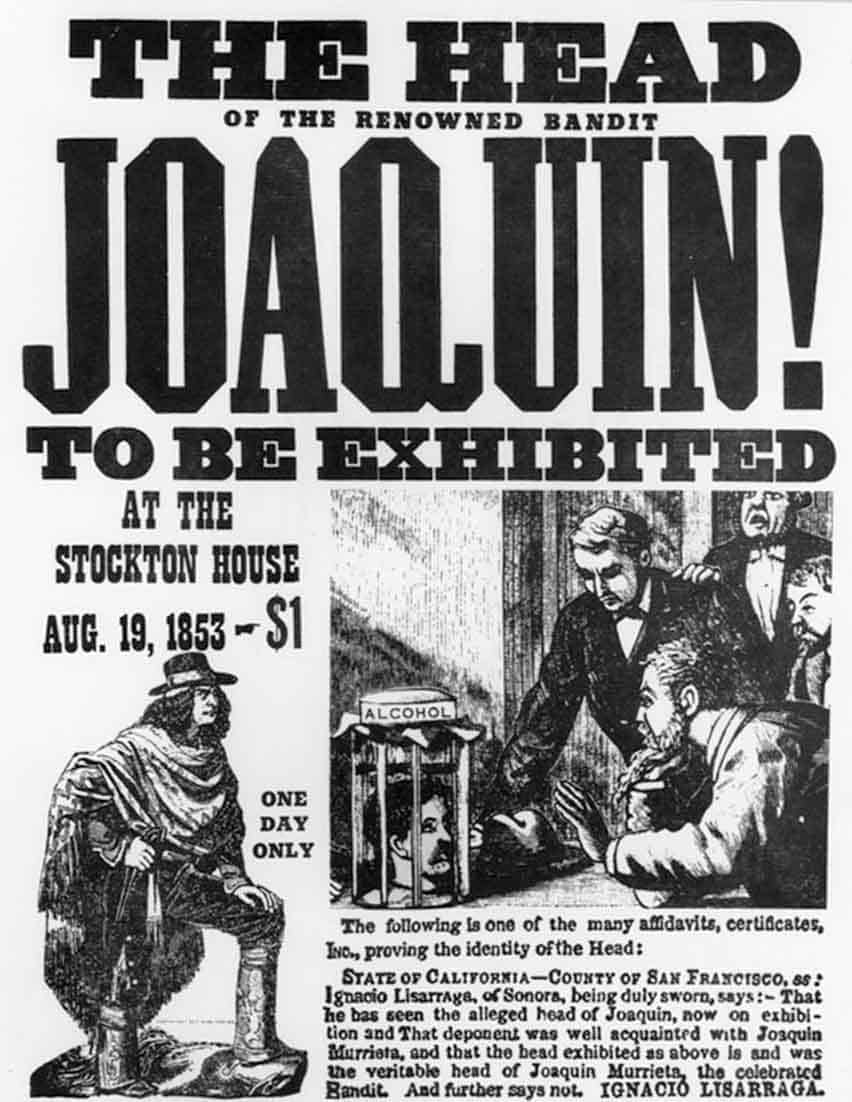

Love then cut off Murrieta’s head, as well as Three-Fingered Jack’s right hand, preserving them in jars of brandy. Love thought that exhibiting the body parts would further intimidate Mexicans and send them a message about opposing the authorities.

Love soon returned to San Francisco and began his grisly exhibitions — displaying the head in Mariposa County, Stockton and San Francisco for $1 a view. He and Bigler thought that these exhibitions would prevent Murrieta from gaining more relevance among oppressed Mexicans, but the opposite was true.

The legend of the Mexican Robin Hood spread far and wide and became more spectacular with each telling. Mexican Californians identified with this avenging hero’s pain and sorrow and saw him as a crusader against oppression by the “gringos.”

For the next 25 years, rumors about Murrieta ran rampant: The theft of gold shipments continued after his alleged death, and some said that Murrieta had never been captured or killed — that the Rangers fabricated the whole story to reap the US $5,000 bounty.

Furthermore, people close to Murrieta — including his own sister — proclaimed that it was not his head. People reported sightings of Murrieta, saying they had just received gold from him.

Then, in 1875, the San Francisco Herald newspaper received a letter signed by Joaquín Murrieta, claiming he was still alive adding, “I still have my head.”

No one knows for sure what happened to Murrieta, but some say he didn’t die until the end of the 1870s and that his body is buried in a Jesuit cemetery in the town of Cucurpé, Sonora.

Murrieta’s legend reveals the complicated relationship that existed between Mexico and the United States after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 — which started the first wave of Mexican migration to the U.S.

Everyone loves stories of heroes seeking revenge, and especially stories of outlaws stealing from the rich to give to the poor, so Murrieta’s legend has unsurprisingly endured for almost 200 years. By 1919, Johnston McCulley had recast Murrieta as the character El Zorro in a five-part serial for an American audience, “The Curse of Capistrano,” published by a pulp fiction magazine. In McCulley’s story, Zorro’s real name is Alejandro Murrieta.

Throughout the years, Murrieta’s legend has inspired more than 15 books, including one by Chilean Nobelist Pablo Neruda; five comic strips (including “Batman”); 16 songs; and 20 TV shows, radio programs and movies — one of the most famous being the romanticized film “The Mask of Zorro,” starring Antonio Banderas.

The most recent version of the legend can be seen in the newly released (2023) TV series “The Head of Joaquín Murrieta,” available on Amazon Prime.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.