San Miguel de Allende, lauded by Condé Nast Traveler as the “Best Small City in the World” five times, and designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008, was not always the vibrant city it is today.

Established in 1542 as a Spanish colonial settlement, San Miguel de Allende flourished during colonial times with significant wealth derived from nearby silver mines. This prosperity fueled the construction of grand mansions, churches, and public buildings that showcased the city’s opulence.

However, the War of Independence (1810-1821) and the Revolution War (1910-1917) had devastating effects. The cessation of the region’s silver mines, which had been the city’s economic backbone, led to widespread hardship. Social and political turmoil further exacerbated the decline and many residents abandoned their homes in search of better opportunities elsewhere.

The grand architecture fell into disrepair and by the early 1900s, the town teetered on the brink of becoming a ghost town. In 1926, the Mexican government intervened, declaring it a national historic monument. This designation marked a transformative moment, signaling a commitment to revitalizing its significance. With strict regulations in place to protect its colonial ambiance, the town embarked on its renaissance.

Stirling Dickinson is a man who played a most notable role in shaping the modern history of San Miguel de Allende. Born in 1909 in Chicago, he hailed from a prestigious family background. After graduating from Princeton with a degree in art and architecture, he embarked on a six-month tour of Mexico with his classmate Heath Bowman, resulting in their adventure book “Mexican Odyssey,” ranking in at No. 10 in the Chicago Daily Tribune bestsellers list.

Dickinson and Bowman then authored another travel adventure, “Westward from Rio,” before heading to San Miguel de Allende in pursuit of a peaceful setting to work on their next book, “Death Is Incidental” inspired by the Mexican Revolution This journey was prompted by the invitation of Jose Mojica, a Mexican opera singer and Hollywood film star who had built a home for his mother in San Miguel de Allende and welcomed the two Americans to experience the town’s charm.

Dickinson and Bowman arrived by train in the early morning hours of February 7, 1937, and rode into town on a mule-drawn cart. Reflecting on their arrival, Dickinson vividly recalled, “I looked up and saw the Parroquia sticking up out of the fog, and I said, ‘My gosh, what a place!’ I think I must have decided at that minute I was going to stay here because 10 days later I bought the house I’m sitting in now,” as recounted in a 1992 interview for the San Miguel Archive Project.

In 1938, Dickinson was appointed director of the Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes, housed in part of the Immaculate Conception convent that had been confiscated from the church by the government following the Mexican Revolution. However, his work in Mexico was interrupted by World War II. From 1942 to 1945 he returned to the United States to serve in Naval Intelligence and later in the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA. Upon his return to San Miguel after the war, Dickinson leveraged his connections to facilitate attendance at the art school on the G.I. Bill that funded free education for war veterans.

Chicago papers and other publications quickly began featuring stories about this emerging artist enclave nestled in the mountains of Mexico, sparking a period of prosperity for both the school and the town. Over 6,000 veterans applied to enroll following the January 1948 issue of Life magazine, which lauded San Miguel de Allende as a “G.I. Paradise where veterans go to study art, live cheaply, and have a good time.”

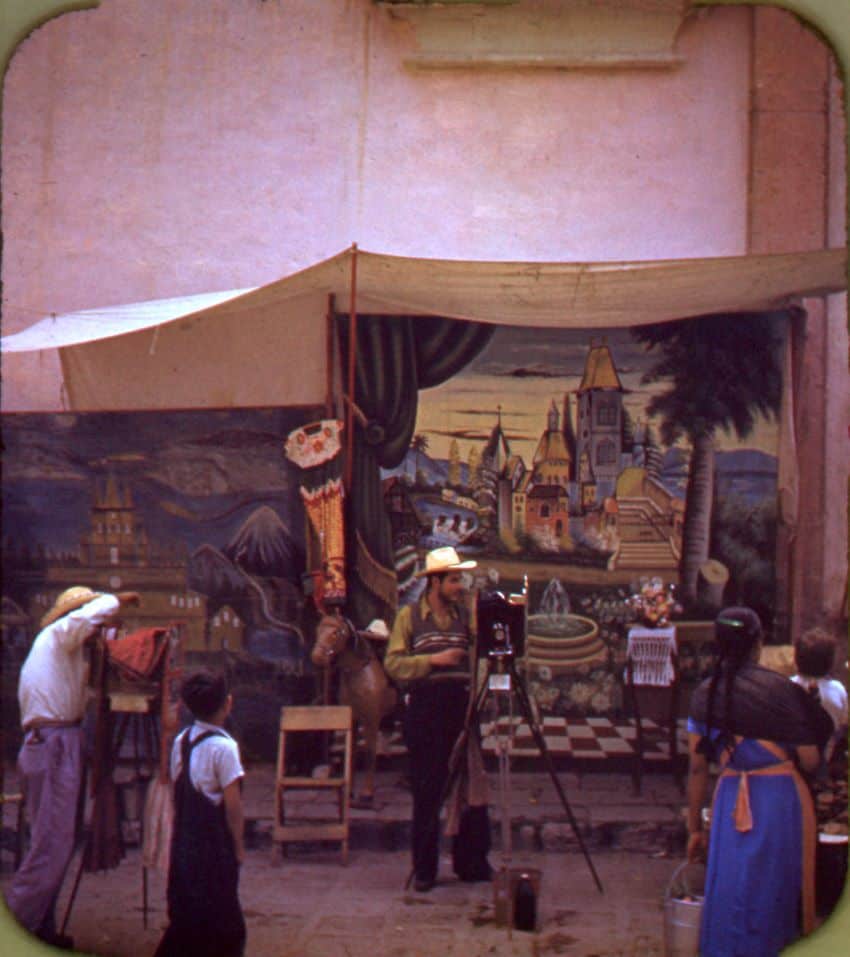

San Miguel began to script a new chapter in its history, with education and art taking center stage. The arrival of new students and visitors brought an influx of income for local merchants and service providers. This increased prosperity was evident in the construction of hotels, and the city flourished remarkably.

Trouble came when a recently arrived member of the faculty, noted Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, got into a dispute over funding with the art school’s manager. Siqueiros led a walkout of students and staff with Dickinson’s support. In 1946, the Bellas Artes school was taken over by the Ministry of Education of the State of Guanajuato and now houses the government-run Centro Cultural Ignacio Ramírez.

Felipe Cossío del Pomar, a Peruvian artist and diplomat in exile who had previously established the Instituto de Bellas Artes with encouragement from intellectuals Alfonso Reyes and José Vasconcelos, was resolute about ensuring San Miguel had a top-tier art school. In 1950, he, along with his public relations expert Stirling Dickinson, the former governor of Guanajuato, Enrique Fernández Martínez, and his wife, the American Nell Harris, founded another art school, Instituto Allende.

By 1960, Instituto Allende had become pivotal in drawing new residents to the town, primarily through its acclaimed art education programs. San Miguel’s economy continued to thrive with the influx of tourists and expatriates enticed by the vibrant arts scene, affordable living, and a welcoming international community.

San Miguel de Allende continues to be a beacon for creativity and inspiration with numerous schools and galleries, drawing people from around the world who come to experience its unique charm and contribute to its ongoing legacy.

Sandra Gancz Kahan is a Mexican writer and translator based in San Miguel de Allende who specializes in mental health and humanitarian aid. She believes in the power of language to foster compassion and understanding across cultures. She can be reached at: sandragancz@gmail.com