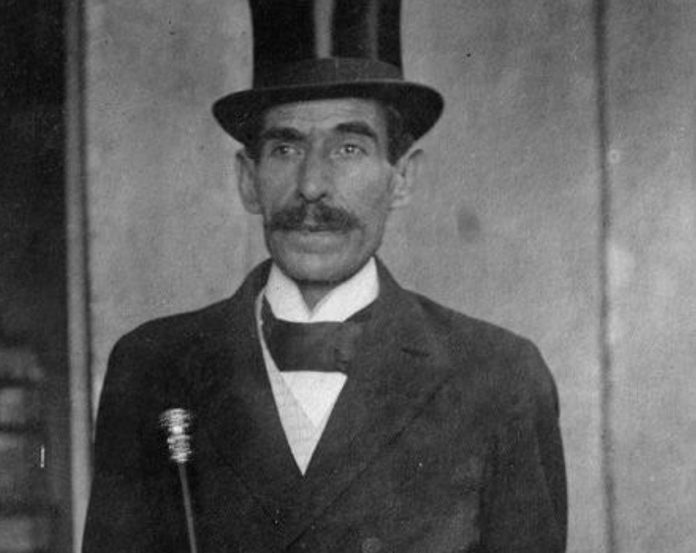

One of the most colorful — and perhaps tragic — characters in the political history of Mexico was Don Nicolás Zúñiga y Miranda. Known as the “perpetual candidate,” he ran for president nine times in 30 years (1894–1924), never garnering more than a few thousand votes.

After each defeat, he would declare electoral fraud and announce that he was the “legitimate president” of Mexico.

Zúñiga y Miranda was born in Zacatecas in 1865 and studied jurisprudence in Mexico City, although there is no evidence he ever practiced law. He first rose to fame in 1887 when he claimed he had invented a machine — the seismeon — that could predict earthquakes. With chance in his favor, he successfully predicted an earthquake in 1887.

Shortly afterward, he predicted a second earthquake would happen on August 10 of the same year, one that he said would cause the Popocatépetl volcano to erupt and would destroy Mexico City.

People panicked, abandoned their homes and left the city or gathered in squares and parks on the designated day. But when the earthquake didn’t occur, an angry mob delivered Zúñiga y Miranda a public beating that sent him to the hospital.

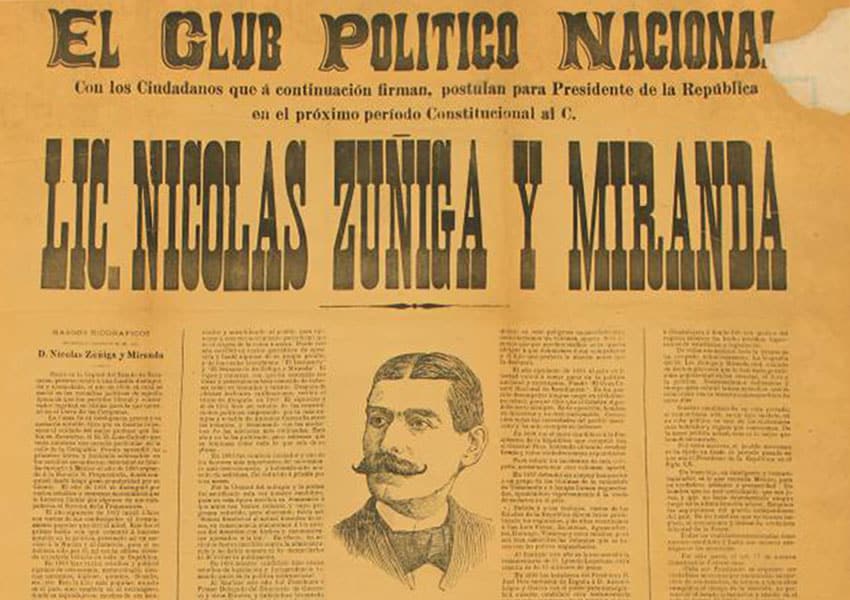

He disappeared from public view for a while, then suddenly reappeared in 1896, announcing he would run as “the people’s candidate” against President Porfirio Díaz.

A group of men opposed to Díaz told Zúñiga y Miranda that they would back him, hoping that he could defeat Mexico’s dictator, who had been elected in 1876 and with the exception of a few years where he was ousted, had stayed in power ever since.

But Díaz arrested Zúñiga y Miranda and imprisoned him a month before the election, releasing him only after the election was over and Díaz had been reelected.

After his release, Zúñiga y Miranda founded the newspaper La Voz Zúñiguista (The Voice of Zúñiga) and published an article titled “I Am the President.” Upon seeing it, Díaz was enraged and ordered that Zúñiga y Miranda be sent back to prison for another six months.

Upon this release from prison, however, it became obvious that the months of solitary confinement had impaired Zuñiga y Miranda’s mental faculties. The people started referring to him as el loco.

But he was persistent and continued to run for president as an independent candidate. He ran against Díaz four times, as well as against Francisco Madero (1911), Venustiano Carranza (1917), Álvaro Obregón (1920) and Plutarco Elías Calles (1924).

He was also a candidate in 1914. Mexican presidential elections have always been contentious, but 1914 was one of the most interesting scenarios.

Francisco I. Madero was elected president in 1911 but assassinated in 1913 by Victoriano Huerta, who then took his place as president. People in the capital were so angry that they voted for Zúñiga y Miranda instead, even though he was by then a known loco.

He received more votes than Huerta, but there were other contenders in the race, and the Mexican Revolution had just entered a new stage of warring factions. The election was annulled, and Zuñiga y Miranda lost yet again.

After each defeat, he would declare electoral fraud and insist he was the legitimate president.

According to Ecuadorian historian Rodrigo Borja Torres, author of a biography of Zúñiga y Miranda, newspapers of the time wrote that “Díaz realized that Zúñiga was not a danger to him… The political class took [his candidacy] more as a joke.”

But Zúñiga y Miranda kept declaring himself the “legitimate president” and walked the streets of Mexico City greeting people as if he were. It made him a source of amusement and derision: people would mockingly greet him with “How are you today, Mr. President?” or “Good morning, Mr. President.”

Historians say that in moments of lucidity, his proposals were populist in nature. During his one-man campaigns for president — he had no staff and he did no debates — he promised that if he won, eggs would cost two centavos, rents would drop by 80% and students would have open accounts at the best restaurants and free scholarships to study abroad.

He had no real proposals for achieving these lofty promises.

Historian William H. Beazley recounts that Zúñiga y Miranda was sincere in his awareness of social problems of the time and thought that poverty, especially rural poverty, impeded the nation’s progress.

But at one point, he proposed teaching jiu-jitsu tactics to the Mexican army. He also suggested a meeting of municipal authorities to analyze the effect the stars had on international politics.

During World War I, he announced he was organizing a séance — he called himself a spiritualist — in order to invoke the spirits of Aristotle, the King of Spain, the Kaiser of Germany, the King of England and the Tsar of Russia as a way to achieve peace in Europe.

And so he became famous as the “perpetual candidate.” Historians have studied him with great curiosity, books have been written about his life, newspapers have likened him to Don Quixote de la Mancha and his character makes an appearance in Juan Bastillo Oro’s 1944 film “Mexico of my Memories.”

Zúñiga y Miranda was also immortalized by Diego Rivera in 1947 in his mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park,” where he is pictured speaking with Porfirio Díaz while a newsboy stands behind them holding up a newspaper announcing Zúñiga y Miranda’s candidacy for president.

Was he a madman or just another politician obsessed with becoming president? Probably both.

Historian Borja Torres portrayed him as a calm gentleman who would go crazy each election year and enter a state of fury in his desire to be president.

Perhaps historian Guillermo Mellado in his book “Don Nicolás de México” best sums up his life with this anecdote:

One morning, Zúñiga y Miranda awakened early. Still in his underwear, he went to the dresser and removed a tricolor sash from a drawer. Reverently, he crossed it over his chest, turning from side to side in front of a mirror to admire his reflection.

When his landlady walked in, he told her, “Don’t go. I called you because I wanted you to be the first lady to recognize me as the President of the Republic.”

In 1925, an impoverished Zúñiga y Miranda died in the Mexico City neighborhood of La Merced. Although he had made a career of running for president, he never achieved his dream of actually becoming the president of Mexico.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.