If you’re living in Mexico, or if you visit often, learning the language clearly makes your time here a lot easier and way more interesting. When your Mexican friends are laughing at something, for example, you’ll be able to join in the fun.

I don’t have a facility for foreign languages. I’ve struggled to learn Spanish. But it’s been worth the effort.

I first came to Mexico in 1997 to photograph Day of the Dead events. Other than hola and adiós, I remembered nothing from my high school Spanish almost 25 years earlier. But somehow, I figured I’d be OK.

But after a few days of wandering around Mexico City, often getting lost because I couldn’t ask for directions, I decided I needed to learn the language.

I wanted to start with something simple but important. So I asked Fernanda, one of my bilingual friends here, to teach me how to say “I’d like a coffee to go” in Spanish.

She said, “Just say, ‘Quiero un café para llevar.’” We practiced it a few times and then I headed out.

I hit every coffee shop I came across. I got my coffee. No problem. My confidence grew. After the third or fourth stop, I added a little wave of my hand, something casual but that clearly showed I knew my way around the language.

After a couple of days, I decided to expand my vocabulary. I asked Fernanda how to say “I’d like a coffee and doughnut to go,” doughnuts being, in my opinion, one of the world’s most important foods.

“Just say, ‘Quiero un café y un postre para llevar’ and point to what you want,” she told me.

I headed out and stopped in every coffee shop I saw, happily walking out with my coffee and doughnut. The caffeine and sugar kept sleep at bay for several nights, but since I was awake, I kept practicing the new phrase, adding inflections to different words.

At this rate, I figured it would only take me a couple of months to truly master the language.

Then I hit a bump in the road. Or, more correctly, a tope.

I had confidently entered a coffee shop, asked for a coffee and un postre and pointed to what I wanted. The young woman behind the counter said something incomprehensible, so I repeated what I’d said.

She repeated what she’d said.

Why couldn’t she understand me? I was pretty sure she understood Spanish.

I raised my voice slightly and talked more slowly — because that always works, right? But no, we got nowhere.

Mystified, I kept pointing to the doughnut I wanted. She let out a long sigh, handed me the coffee and doughnut and turned away.

As I was walking out, I noticed a sign that, even with my limited Spanish, I was able to interpret — the day’s special: a coffee and two doughnuts for the price of one.

So, during that first trip, I bought a Spanish-English dictionary and memorized a few more words. By my second trip, I had somehow convinced myself that I had advanced to the conversational level.

In other words, I got cocky. I would pay the price.

I was again in Mexico City with Fernanda when we met some of her Mexican friends. With a handful of Spanish words now under my belt, I believed I had a command of the language.

OK, maybe ‘command’ is a little misleading: I understood more of what was being said. When I said something, I did OK as long as I kept words and phrases simple and in the present tense.

So there we were, having a conversation. Well, they were having a conversation, and I was doing a lot of smiling and nodding at what I hoped were appropriate moments. (I’ve learned since back then that you become very good at reading body language when you don’t fully understand what’s being said.)

Then, someone asked me something. I didn’t understand, so Fernanda said he was asking what kind of work I did.

I froze for a moment as they waited for my reply, which I decided would be in Spanish — my (nearly) second language.

I couldn’t think of the word for “writer.” But then some words popped up in my memory: I knew that pan meant “bread” and that panadero meant “a baker.” Similarly, I remembered that zapato meant “shoe” and zapatero meant “shoemaker.” And I’d learned the word escribir (to write).

Perhaps you see where this is going.

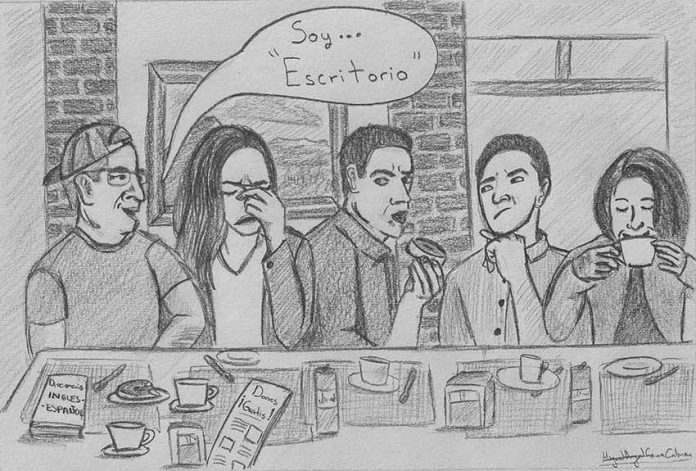

So, confident in my choice of words, I actually paused for a moment and gave a modest flourish of my hand as I replied, “Soy escritorio.”

Now, if you’re a Spanish speaker, you already know why they all looked at me like, “What the…?” But I was puzzled.

Fernanda leaned in and whispered, “Do you want to tell them you’re a writer?”

“Of course,” I replied.

“Well, you just told them you’re a desk.”

She quickly explained that escritor, not escritorio, was the word for “writer.”

Back at her apartment, I told her how embarrassed I was.

“That’s nothing,” she told me and then related a story about another American friend who’d been riding Mexico City’s Metro and wanted to know how to say, “Excuse me” when he got off the subway car.

She taught him to say, “Disculpame (pardon me).” So, whenever he exited the Metro, that’s what he said.

Or thought he did.

The next time he saw her, he told her that people were looking at him strangely whenever he exited the train and uttered the phrase she’d taught him.

“What did you say?” she asked.

“What you taught me: escúpeme.”

Again, some of you are ahead of me.

He was saying “spit on me.” I don’t think anyone actually did, but I’m sure they all got quickly out of his way.

After living in Mexico for almost four years, I’m now able to conduct interviews and have conversations completely in Spanish. I don’t claim to be fluent, but I believe I’m proficient; I can almost always choose correctly between ser and estar. I freely admit that I’ll probably never get a handle on the difference between para and por or fully understand the subjunctive, but I manage.

Heck, sometimes I’m even able to understand what people are laughing about and can join in.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.