On the morning of September 19, 1985, the lives of millions of Mexicans changed forever in just 90 seconds. I hadn’t been born yet, but my older sister was only three weeks old. My mother, on maternity leave, spent her mornings caring for my sister while my father left early to teach theater at a nearby middle school.

At precisely 7:19 a.m., an 8.1-magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Michoacán. My parents described the terror of feeling the earth move beneath them, dashing into the streets only to find the city scarred by collapsed buildings, the pungent smell of gas from ruptured pipelines filling the air, and neighbours frantically searching for their loved ones.

A dismal aftermath

Mexico City, resting atop an ancient lakebed, endured an amplified impact. The earthquake’s tremors extended to nearly three minutes in some parts, a harrowing eternity beyond the 90 seconds elsewhere. Death toll estimates remain tragically uncertain, with official figures citing between 6,000 and 7,000 fatalities, while survivor groups suggest closer to 15,000. The true number is forever elusive.

The devastation was profound: 412 buildings were obliterated, and over 3,000 were severely damaged. Iconic structures like the Regis Hotel, the Conalep on Balderas, Televisa Chapultepec, the Centro Médico, the Juárez Hospital, a housing tower in Tlatelolco, the Juárez multifamily complex, and the Ministries of Labor, Communications, Commerce and the Navy succumbed to the quake’s wrath. Housing losses were equally dire, with 30,000 homes destroyed and another 60,000 severely damaged, leaving 30,000 injured and 150,000 displaced. The economic toll on infrastructure soared to an estimated US $4 billion dollars, equating to 2.7% of the national gross domestic product (GDP) at the time.

In the quake’s dismal aftermath, with communications and electricity down and the very air fraught with danger, Mexican civil society sprang into action. Makeshift shelters emerged, citizen-led neighborhood committees formed for mutual protection, and renowned volunteer rescuer teams like Los Topos mobilized with astounding alacrity. Yet, the earthquake starkly revealed the Mexican populace’s vulnerability to natural disasters and highlighted the systemic failures in emergency response and preventative measures.

Creating SASMEX

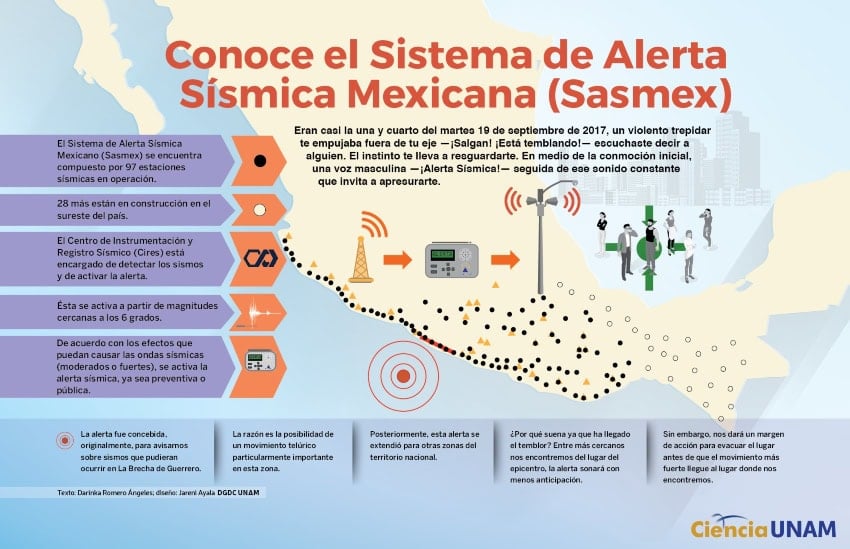

Seizing upon this moment of reckoning, Mexican engineers and scientists resolved to harness technology for future safety. Realizing the potential offered by the distance between the coastal seismic zones and inland cities, they understood that seismic waves traveling at only 3.5 kilometers per second could allow a brief but crucial window for an alert system. Thus began the journey toward the Sistema de Alerta Sísmica Mexicano (SASMEX), the world’s first early earthquake warning system.

In 1986, the Foundation for Seismic Instrumentation and Recording (Centro de Instrumentación y Registro Sísmico, A.C., or CIRES) was established as a civil association under the auspices of the Javier Barros Sierra Foundation. Barros Sierra, a distinguished mathematician, engineer, academic and businessman, played a pivotal role in shaping Mexico’s academic and scientific landscape, and we’ll delve into his legacy soon. The foundation’s mission was clear: unite engineers to research and develop cutting-edge technology aimed at reducing seismic risk.

One standout figure in this story is engineer Juan Manuel Espinosa. Alongside Gerardo Legaria, Humberto Rodríguez, Samuel Maldonado and Bernardo Fontana, Espinosa began designing an earthquake alert system in 1989, inspired by a model they initially developed as undergraduates. After years of relentless effort — much of it driven almost single-handedly by Espinosa, with support from international organizations and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) — SASMEX officially launched in 1991. Its initial network comprised 12 seismic sensor stations primarily along Guerrero’s coast, marking the birth of the world’s first early earthquake warning system.

Expanding the system

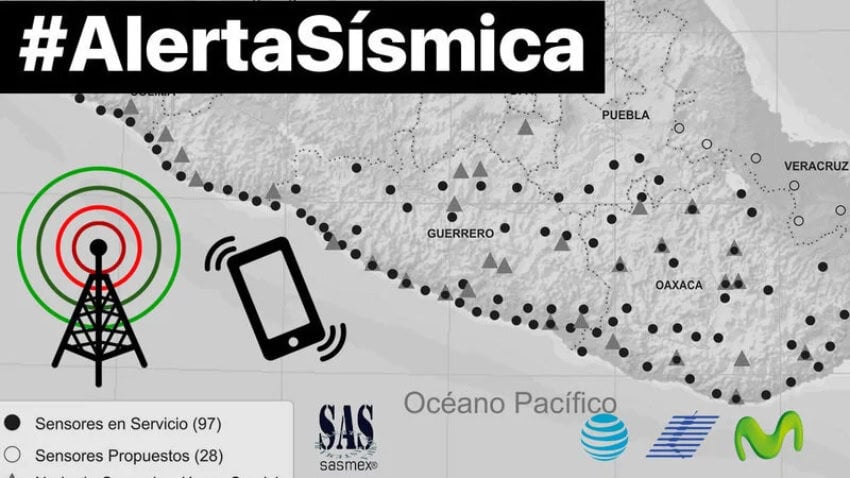

The impact was immediate and profound. In 1999, following a 6.7-magnitude quake, Oaxaca’s government enlisted CIRES to develop its own seismic alert system, which became operational in 2003. Today, SASMEX boasts a network of 97 accelerographic stations spanning Mexico’s Pacific coast—mainly in Guerrero, Oaxaca, Colima and Michoacán. When the sensors detect energy levels exceeding predetermined thresholds, they send electromagnetic signals to urban centers, providing residents with between 20 and 120 seconds to take protective measures.

This sophisticated system employs three algorithms to measure maximum and cumulative ground acceleration. When these signals surpass critical limits, they relay data to city control stations, where officials decide whether to issue alerts.

111 Alerts

Since its inception, SASMEX has detected approximately 9,800 seismic events and issued 111 alerts, saving countless lives in the process.

Historical milestones underscore its significance. On May 14, 1993, SASMEX detected a 6.0-magnitude quake and predicted its arrival in Mexico City with 65 seconds to spare, prompting early warnings that likely saved lives. Again, on Sept. 14, 1995, the system forecasted a 7.3-magnitude tremor near Copala, Guerrero, with 72 seconds of warning. The prompt response to these alerts demonstrated how well-prepared communities can mitigate disaster … when they heed the warnings.

Exceptions

On September 19, 2017, the echoes of a fateful day resound vividly in my memory. Nestled in my apartment on the sixth and top floor of a Colonia Roma building, where Jalapa meets Álvaro Obregón, I stood at the precipice of a much-needed respite. Having just wrapped up an exhaustive campaign for the national analog signal shutdown for TV and radio, my boss insisted I take a break. “Stay home,” he said, a command I readily embraced after two years without a true vacation.

It was one o’clock in the afternoon, the kind of hour meant for leisurely breakfasts when every minute stretches luxuriously before you like an unfurling daydream. As I set my modest bowl of oatmeal down, I watched as it leaped on the table before me. Underfed and weary, I first mistook the lurch for dizziness until the curtains began to whip with violent fervor. The tremors intensified, the earth beneath my feet rolling with such force that standing was a near impossibility. I was torn between the instinct to flee and the reality —the sixth-floor reality — that escape to street level was but an illusion. Instead, I turned my focus upward, crawling towards the rooftop, the stairway a daunting challenge with each step.

The rooftop door swung wildly, and a piece of wood became my ally against entrapment, yet my grasp on balance was tenuous. Emerging onto the roof, water splashed against me — not rain, but the overflow from the rooftop tank — forcing me back until I clung to the sturdy embrace of a nearby wall.

The 2017 earthquake

Looking out towards Reforma, the city was shrouded in grim plumes of smoke, buildings crumbling into dust-laden sighs, harboring souls within them whose fates I dared not contemplate. Smoke columns rose again when I turned towards Condesa, searing the horizon ever closer, and I feared our building’s number would soon be called.

In an odd twist of survival’s logic, a calmness settled over me with the naive notion that there, on the top floor, I’d have a better chance of getting out. Feeling safer, my mind raced to my sister, working in a vertigo-inducing tower near C.U., and to my parents in Puebla. Fear seized me once again, and as soon as the tremors ceased, I found myself hurtling towards the street, driven by some primal compulsion.

Every door I passed gaped open, rooms emptied violently onto floors now cracked and yawning beneath me. Outside, I saw a street vendor whom I greeted every day. We clung to one another, tears flowing unbidden. “I thought you’d fall, mi niña, I thought you’d fall!” I was trembling.

The air brimmed with the acrid scent of gas. People running and screaming, military trucks speeding down Álvaro Obregón toward a collapsed building just a few meters away. I lived a block from the Álvaro Obregón hospital and saw — like in an apocalyptic movie — nurses still crying as they set up makeshift operating rooms on the median strip, newborns in bassinets, doctors shouting instructions in desperation.

“All gone to hell,” my mind echoed the disorder around me. Yet, from chaos emerged a beacon — my sister — and shortly after, my father, arriving from Puebla with divine speed. “Mom is okay,” he shouted. We were safe, united, but our city lay exposed, fragile beneath the brutal hand of nature’s reminder: the 7.1-magnitude earthquake that cracked the earth 120 kilometers from the heart of Mexico City, claiming 330 lives and sounding an urgent call for proximity in seismic warning stations.

Adapting SASMEX

In the technical realm of earthquake preparedness, the SASMEX model has become a lodestar, guiding nations like Chile and Japan in their development of electromagnetic alert systems. Even the reticent ground of California bends its ear to Mexico’s seismic foresight, tailoring adaptations to shield its own.

A subtle reminder

It is often those who labor quietly, below the surface of recognition, whose contributions hold the most sway. Such is the work of Engineer Juan Manuel Espinosa. His efforts resonate profoundly for the 17.5% of Mexicans residing in Mexico City and the greater metropolitan area, and for those astride the Cocos Plate in Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Chiapas.

A heartfelt salute, then, to the engineers of Mexico, those unsung architects of safety, whose ingenuity cradles us from vulnerability. And though my heart quivers at the sound of the Alerta Sísmica, triggering an adrenaline rush that’s hard to quell, I remind myself: it grants us seconds, precious moments to preserve life — a sound worth its weight in salvation.

María Meléndez is a Mexico City food blogger and influencer.