For 300 years, starting in the early 1500s, the Spanish Empire was the largest the world had ever known. Marriages and wars expanded Spain’s possessions in Europe, and it held a colonial empire in America that stretched from the modern Northwest United States to the tip of Argentina. Spain had a vast income, with a major contribution coming from bullion from America, much of which was reinvested in trade with Asia. However, this considerable income was swallowed up by endless and expensive wars, leaving the Spanish monarchy permanently balanced on the edge of bankruptcy. Behind the pomp of the royal court and the ships-of-the-line, the empire was a crumbling mess, kept afloat by bank loans.

Spain’s colonization of the East Indies transformed the relationship between Europe and Asia. For 1,600 years, Europeans desiring Asian goods could only purchase commodities that passed from merchant to merchant along 6,000 kilometers of the Silk Road, a trade network that linked China to Southern Europe and North Africa. This path closed in 1453, after the Ottoman Turks took Constantinople, making Europe’s ongoing search for a sea link to Asia more urgent than ever.

It wasn’t until 1498 that Vasco de Gama successfully circumnavigated Africa, allowing European merchants to reach the markets of Asia by sea. Spain was largely cut out of a route dominated by Holland and Portugal, but in 1513 the Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama and sighted the Pacific Ocean. After 20 years, Columbus’s dream of a westward route to Asia was alive once again.

East-to-west travel was made possible by the trade winds, and 1565 saw a small Spanish settlement established in the Philippines by a conquering force that had set out from Mexico. Discovering a route back to Mexico proved more difficult, but by sailing north as far as the 38th parallel, Basque sailor Andrés de Urdaneta picked up favourable winds and currents and sailed into Acapulco with a small cargo of cinnamon. This was a poor return for such a long and dangerous trip, and the Spanish colony in the Philippines remained improvised, isolated and in danger of abandonment.

This changed in the early 1570s when the Spaniards in the Philippines, now relocated to Manila, were able to purchase the contents of a few Chinese junks, allowing them to send a consignment of porcelain and silk to Mexico. In 1574, six junks are recorded as sailing into Manila and each year a growing number of ships from Japan and China filled the Manila warehouses with luxury items including silk, porcelain, beeswax, mirrors, gold and Persian rugs. What drove the trade was the Chinese losing faith in their paper money and seeking the security of silver. Spanish silver could double in value when shipped across the Pacific, and their American colonies had the biggest mines in the world.

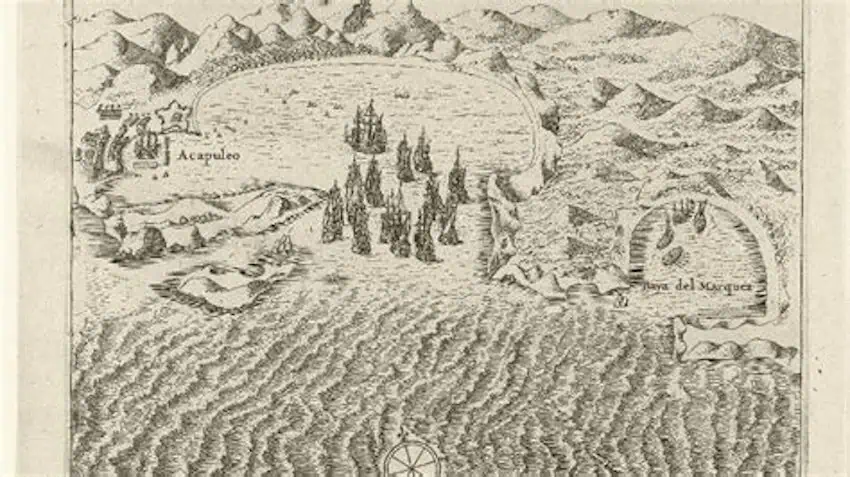

The port of Acapulco was selected as the American terminus for the Manila trade. It was relatively close to Mexico City, and there was little fault to find in a harbor that was safe from storms and so deep that on occasions a ship might tie up to trees rather than drop an anchor. The problem was not the harbor, but the town. Simón de Anda, an 18th-century governor of the Philippines, complained of Acapulco’s “heat and its venomous serpents, and the constant trembling of the earth. “All the treasures of this world could not compensate for the necessity of living there or of traveling the road between Acapulco and Mexico,” he wrote.

The new trade with Asia changed everything. Each year, great galleons known as Nao de China or Nao de Acapulco — the China ship or Acapulco ship — left Manila loaded with all the wealth of Asia. By the 16th century, these galleons were the biggest ships in the world, weighing up to 2,000 tons. Most were built in the Philippines, making use of tropical hardwoods. Even so, there was little room for comfort on a tightly packed ship. Supplies usually ran low mid-passage, forcing the ship’s crews — generally Filipino sailors and Spanish officers — to survive on hard biscuits, rainwater and any fish they could catch. The poor diet inevitably led to scurvy and lack of hygiene was liable to cause an outbreak of other diseases.

While the goods ships carried were varied, it was tightly bound bundles of silk that made up the core of the trade. Asian silk was considered superior to European cloth, particularly as it was easier to dye, and the market was expansive. Silk was used for everything from an official’s expensive cloak to the simple headscarves women wore when leaving the house.

Dates for sailing were set by Spain but ultimately subject to winds and the storm season. The trip from the Philippines to Acapulco, with its long northern circuit, might take six months, and the ships were under command to depart Manila by the end of June. If all went well, they would reach Acapulco around December.

On the return trip, they were expected to depart from Mexico no later than the end of March and travel via Guam, where the galleons were the main link to this smaller colony. This was the more direct and shorter journey and ships hoped to reach the Philippines before the typhoon season started in May. These galleons were the largest and best-armed ships in the Pacific and sailed without escort. It was not only their size and cannon which protected them, but the vastness of the ocean. The real danger from pirates would be at the start and the end of each trip, and it was not unknown for an escort to be sent out as they approached land.

In Acapulco, as the expected date for the arrival of the galleon approached, the population of the port would grow from 4,000 or so poor residents to 12,000 merchants, laborers and hawkers from around the world; a cosmopolitan community of Indians, Spaniards, Chinese, Peruvians, and Filipinos. There might even be a few Africans who had been brought to Asia on Portuguese ships calling in at Mozambique. However, once the fair was over, anybody who could leave did so. As a result, while Acapulco was the center of a trade route that rivalled the wealth of Genoa and Venice, there was little investment in the town. There was a church, and the San Diego fort was completed in 1617. A few more solid buildings served as the headquarters of the treasury, and a row of three-story houses appear to have belonged to merchants.

However, it is difficult to build up a history of the settlement from the few surviving sketches, as buildings that appear in one print have disappeared a century later. All the artists were keen to show the harbor busy with galleons and small craft, a reminder that Acapulco was an important Pacific harbor, not totally reliant on the one yearly arrival. However, there is also a likelihood that artists used their imagination to portray the town, and its commerce, a little grander than it was.

God willing, this year’s galleon would be spotted by small ships sailing off the Mexican coast, and news of its approach would be rushed to Mexico City and Acapulco. As the ship entered harbor, there was a cannon salute between ship and castle, and officials would come aboard to check the cargo. Goods were all tightly sealed, both against the damp and to cram as much as possible into every available space. Opening these tightly packed bundles would both be time-consuming and risk exposing valuable goods to the weather, so the paperwork issued in Manila was traditionally accepted.

On the rare occasions when a diligent official demanded a more rigorous inspection, it would bring complaints and protests from merchants and the town’s officials. The report was rushed to Mexico City for approval and for the taxes to be allocated. Only when permission arrived from Mexico City could the goods be loaded onto lighters, placed on the beach, and from there divided between the warehouses. Passengers could now disembark and head for the hospital or the church. The ship was inspected for any concealed goods, then brought to the shipyard to be prepared for the return journey, perhaps only ten weeks away.

The Acapulco fair was dominated by agents representing the big wholesalers in Mexico City and Puebla, men responsible for millions of pesos who dealt directly with the Manila traders and expected to have some control over this year’s prices. These important middlemen were aware that there was a strict window for the Manila merchants to start the return journey, and the closer they came to the departure date, the more anxious they would be to finalize a deal. One trick was to delay the start of the fair as long as possible, demanding the opening coincide with one of the upcoming religious festivals. During the early years of the fair there was a powerful third force, with the traders from Peru, rich with coins from the world’s biggest silver mines and always likely to undercut their Mexico City rivals.

If the big wholesale transactions were the main event, there was no lack of action around the fringes of the market. Officers from the galleon were allowed to bring a quality of goods ashore and seek their own buyers. Some goods made their way ashore by more dubious ways, for while the bureaucracy was multi-layered, the enforcement of the rules was lax. Indeed, it sometimes seems the whole system was designed to encourage smuggling. Indeed, anybody appointed to one of the official positions in the system, expected to become rich, far beyond the means of their paltry salaries.

There were other sources of business too. The ship needed to be stocked with supplies for the return journey, and with Acapulco having limited farmland, nearby haciendas carried their produce down to the town. Then there were the crew with wages to spend, hundreds of porters, the mule drivers and the dockyard workers, all requiring food and entertainment. Those just arrived, mixed with those gathering for the return trip, priests for the increasingly passionate drive to convert Filipinos to Christianity, soldiers, officials, merchants and prisoners being sent into exile. There would have been transactions going on in every tavern and dark corner.

The wealth created by the galleon trade became so expansive, there were fears it might swamp the Spanish economy, draining silver reserves and endangering Spain’s home-grown textile industry. Atlantic merchants, who linked America with Europe, complained that their own trade was being adversely affected by the number of merchants abandoning the eastern port of Vera Cruz for booming Acapulco. From around 1593, Spain struggled to impose some control over the trade. This was largely achieved by decreeing the amount of silver that could be exported each year, as well as restricting transportation to that one single vessel.

No goods could leave Acapulco until the fair closed, but then the caravans of mules would climb into the mountains to start the trek to Mexico City, while the Peruvian ships would sail for home. Some of the goods sold in Mexico City — items that might have originated in Japan or Persia — would be taken to Vera Cruz for shipment to Spain. For three centuries, Acapulco sat at the center of a global trade route. By the late 1700s, the galleon trade was in decline. The easterly route to Asia, via Africa, was opening up to all nations, while so much silver had crossed the Pacific that Asia was losing its desire for the metal.

Three centuries of trading turned Acapulco into a sizable town, and Manila into a great city. The Nao de China also linked New Spain and the Philippines profoundly in a way that persists in the present day. Asian porcelain and silks influenced the style of Central American ceramics and textiles and Filipino sailors may have helped invent tequila, while Tagalog uses dozens of Nahuatl words. The importance of the Manila-Acapulco trade route was acknowledged in 2009, when UNESCO proclaimed October 8 as Galleon Day. A Galleon Museum, with a full-scale replica of a Spanish galleon, is under construction in Manila as the Philippines and Mexico work towards gaining UNESCO World Heritage status for the old trade route.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.