In the Montessori approach to education, children are exposed to sensory activities and materials that help them fully develop their senses of touch, taste, sight, sound and smell, possibly awakening unexpected talents and opening doors to careers their parents might never have imagined for them.

For seven-year-old Pedro Díaz, such an awakening took place simply because he wandered into a workshop across the street from his home.

It was 1941 when the boy began hanging around the workshop of Francisco Navarro, who cut rock from a nearby quarry and sculpted headstones, crosses and vases for the local cemetery of the little town of Ahualulco de Mercado, Jalisco, located 60 kilometers west of Guadalajara.

Cantera stone is composed of silicic minerals that formed millions of years ago through extreme heat and pressure. It is the stone of elegant haciendas: porous, lightweight and beautiful. It is also easy to carve.

The sculptor’s apprentice

One day Don Francisco noticed how closely Pedro was watching him.

“You like this kind of work?” he asked the boy.

“¡Sí, sí!” replied Pedro enthusiastically.

“Okay,” said the sculptor, giving the boy his first chisel. From that day on, Pedro was his apprentice.

“I was fascinated by everything I saw going on at that workshop,” Don Pedrito says, “and when I talked to my mother about it, she said, ‘Son, I want you to become a sculptor. Since Don Francisco Navarro is willing to teach you, I will support you all the way.’”

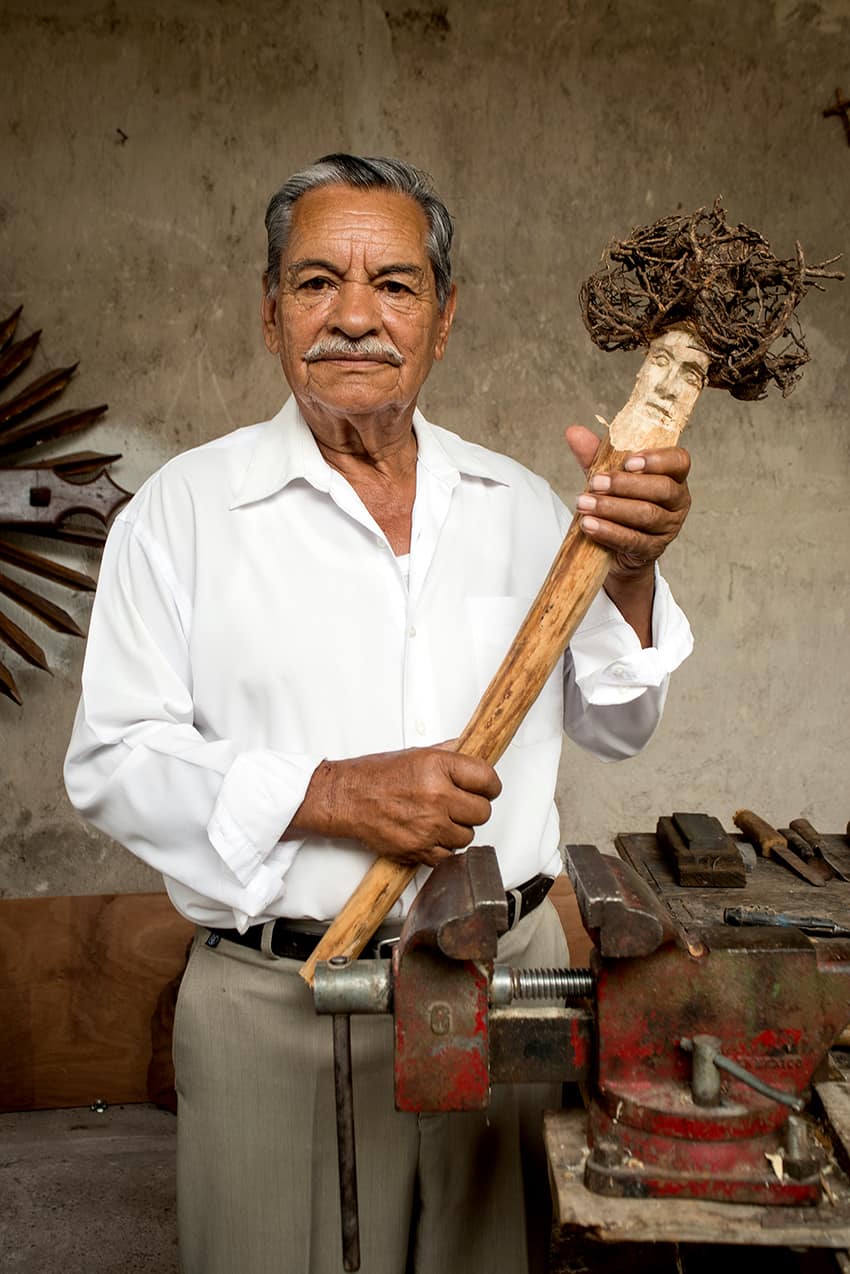

“So at 12 years of age, there I was, making my own figuritos (figurines),” he shares. Don Francisco also took Pedro out into the mountains and taught him how to extract blocks of cantera using drills, sledgehammers, and blasting powder.

The head of Christ

Then, when Pedro was 14 years old, a man walked into the workshop and loudly addressed the owner: “I want you to carve me the head of Jesus Christ!”

When the client had left, Navarro looked at Pedro: “Would you like to do it?”

“Yes,” replied Pedro, “but only if you guide me.”

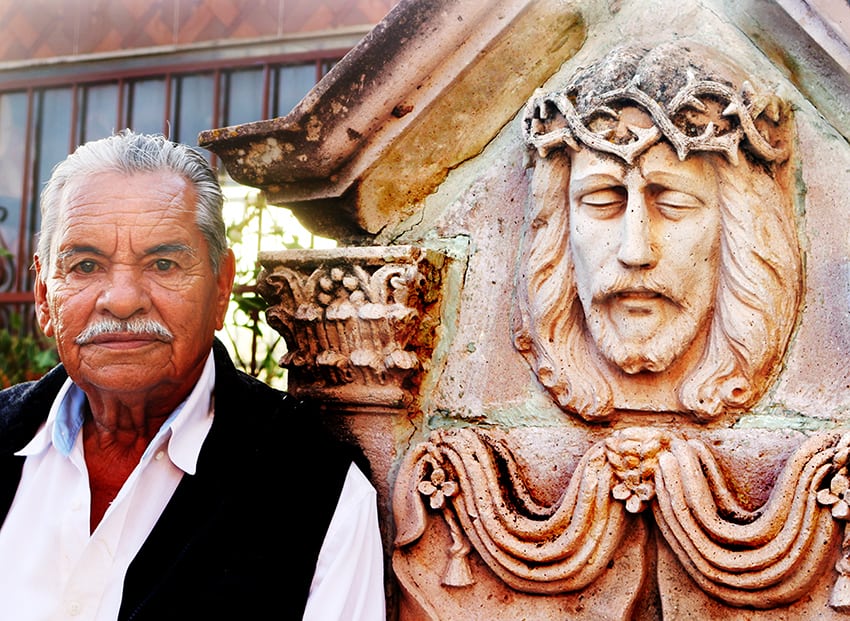

This turned out to be Pedro Díaz’s first work of art. It is carved in pink cantera and measures 60 centimeters high. It can still be seen today in the municipal cemetery of Ahualuco de Mercado.

Sleeping on a bench

In 1951, at the age of 17, Pedro went to Mexico City in search of work, and after three days, he got a job as a general helper at a very old church that was being reconstructed. For a month, he spent his nights sleeping on a nearby iron bench until the architect in charge of the project, José Soto, found out about it and arranged for the boy to sleep inside the church.

One day Soto asked Pedro to bring him a piece of wood and in a few minutes, the architect roughly shaped it into a hand.

“Finish it,” he told the boy, “and tell me when you are done.”

Pedro had it ready in no time and, after being given a few tips by the maestro, was soon put to work sculpting hands, feet and eventually faces for the damaged wooden statues in the church.

At this point, Don José realized that Pedro was doing the work of a sculptor but receiving the lowest salary possible, which was hardly enough for tortillas and a plate of black beans once a day.

Who needs a diploma?

So, after a year and a half of work, he got a raise, and not long after the architect, seeing his talent, sent him off to the prestigious Academia de San Carlos—the first major school of art in the Americas—which he attended, while still working at the church.

At the age of 22 he finished the course but received no diploma because in his life he had only completed three years of schooling. “Don’t worry,” said Don José, “with what you’ve learned, you can work anyplace —who needs a paper?”

Carving cinders

In his younger days, Pedro carved most of his sculptures in wood and stone, but at a certain point, he began to sculpt in a light volcanic rock called tezontle in Mexican Spanish and scoria or cinder in English. Scoria is brittle and completely composed of small, bubble-like cavities. It ranges from black to deep reddish brown and is produced by volcanoes called cinder cones.

Scoria is used for everything from decorative landscaping to innovative sewage treatment.

“Whatever gave you the idea of carving tezontle?” I asked the sculptor.

“Bueno,” he replied, “after living in many different places, I came back to my own territory and I took a trip to the top of Tequila Volcano. About halfway up, I came upon rock that was porous and looked easy to carve. So I brought some pieces of it home and found I liked working in this medium.”

A family of sculptors

“So, I ended up having a workshop here in Ahualulco, with my six children learning and working with other people who joined us, and all of our tezontle carvings were going to the town of Piedras Negras on the border, where many people from the USA would come to buy them. As soon as we had twelve sculptures ready, a truck would carry them up to Piedras Negras and then it would bring back goods from there, for example rubber and leather, that could be made into huaraches.”

Today, Don Pedrito, as everyone fondly calls him, is 89 and no longer sculpting. Still, his works of art can be found throughout Mexico and as far away as California and Texas, proving that if you have talent, you can do a lot without a paper.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.