Before we dive into one of Mexico’s best films when it comes to social commentary, I’d like touch on some diverging self-concepts between my home and host countries.

One of the many differences between the United States and Mexico in terms of culture is the willingness — or not — to criticize our own country harshly. Mexico sees its government as a reflection of themselves writ large. The U.S. tends to sees its government as a force outside of themselves. Both are criticized by its own citizens, but Mexico doesn’t pretend like its government is some outside entity with wildly different behaviors and values than the rest of the population. There’s no talk here of the “deep state,” for example. The secrets are pretty much out in the open.

I’m not just talking about a particular political party here, or even the government alone. I’m talking about the entire culture of the country. Mexicans have a habit of getting philosophical about themselves as a whole in ways that their neighbors to the north tend not to. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard some variation of this conversation:

“But oh, we’re such hypocrites, aren’t we? We say we want a country free of cheating and corruption, but we all lie and behave corruptly in small ways. So what do we expect? We complain about our corrupt government, but tell me, who among us would refuse a chance to get ahead ourselves by cheating? Very few.”

To this, most people in the room fall quiet and nod silently. Perhaps they’re thinking of the time they copied a schoolmate’s homework. Or maybe of another time when they had “a connection” fix their paperwork for them through an “alternate route.”

Ask someone directly if they’ve personally ever done something they shouldn’t have, though, and you’ll see some vigorous head-shaking. This kind of reflection is collective, not personal. Where Americans look for someone specific to blame, Mexicans will argue that the problem is baked in from the start. So who’s really to blame?

Contrast this to the U.S., where many people are quite willing to take personal responsibility for their mistakes. Try to argue that the problem is the system, though, and you won’t get much head nodding. Many might suffer under capitalism, for example, but failure to thrive under it is inevitably seen as the individual’s, not the system’s, fault.

So Mexicans condemn themselves collectively, Americans individually.

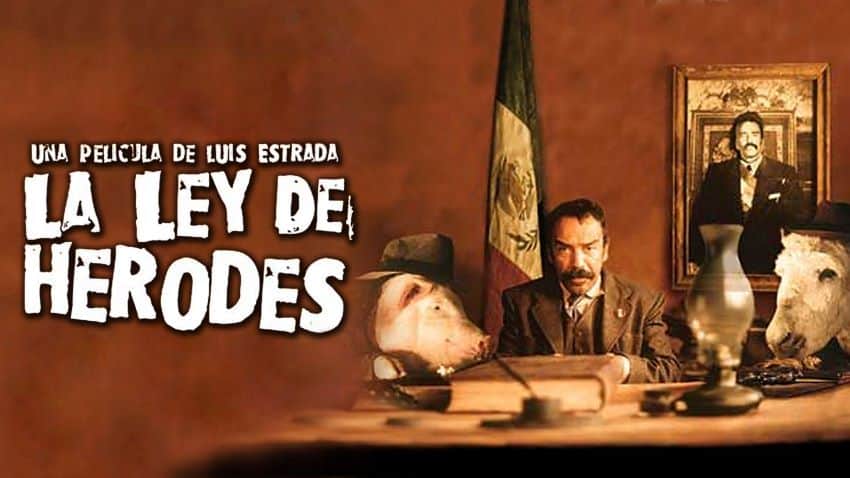

One of Mexico’s best filmmakers, Luis Estrada, is a master at showing how well-intentioned individuals can get sucked into “the system” and come out rotten on the other end of it. His movie “La Ley de Herodes” — released in the U.S. as “Herod’s Law” — is a reflection of this cultural willingness to take a long, hard look at the surrounding circumstances’ influence on the individual.

In my opinion, Estrada is Mexico’s foremost master of social commentary through dark comedy. His films are often described as tragicomedies. They’re funny, but cynically so. In a country where it’s not always the safest move to do so, he’s relentlessly criticized the parties in power. In this movie, it’s the PRI.

“La Ley de Herodes” is a 1999 film that chronicles the path of a low-ranking PRI member in 1949 Mexico. The PRI, or Institutional Revolutionary Party, you’ll remember, ruled Mexico from the period following the Revolution until Vicente Fox of the National Action Party (PAN) became president in the year 2000. During the time in which the film is set, its rule was absolute.

After a corrupt mayor is run out of the town of San Pedro de los Saguaros and killed by its inhabitants, party leaders must choose a successor. They look for someone earnest, easy and a little dim-witted. Finally, they settle on Juan Vargas, a junkyard supervisor played by Damián Alcázar. The party bosses reason they’ll just need someone who will last three or four months.

Vargas is excited that it’s finally “his turn,” and moves to the tiny community full of enthusiasm. San Pedro, of course, is new to him. He’s not from there; in fact, he’s never been to it before.

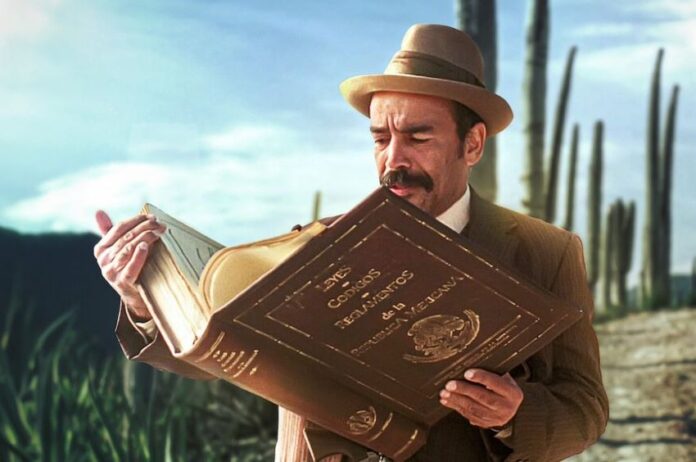

Much to his disappointment, Vargas soon discovers that the job is not at all easy to do. First, the municipality’s money is gone. Second, no one in the town seems to respect him. When he returns to the state capital to ask for more funds since they were “pre-stolen,” he’s given a gun and a copy of the Mexican Constitution.

And this is where he learns the lesson that’s always seemed so endemic in the culture:

“El que no transa no avanza” — He who doesn’t cheat doesn’t get ahead.

Vargas uses both of the tools given to him to collect “taxes” — bribes — and stay on top of things in his little kingdom. We watch hopelessly as he devolves from earnest hero ready to do a good job into corrupt politician without a single saving grace.

This is a defining feature of Estrada films. There are no real “good guys,” only “flawed guys” with mostly good intentions. Sometimes. There is no sense of “the noble poor” who are just as humanly flawed as the rest of us; nobody in his films is morally righteous. And those who come close are never the ones with any actual power.

If you want to take a deep dive into how Mexicans conceive of the corrupting forces of power, then this is a good place to start. You’ll find that most Mexicans know the film well; after you watch it, get ready for some good conversations.

What is Herod’s Law, by the way? Either you screw them or they screw you. You know, like the Biblical Herod who ordered the massacre of all male infants under 2 near Bethlehem, causing a pregnant Mary, Mexico’s favorite Biblical figure to flee?

Put a different way, sometimes you “have” to do unsavory things to survive — or keep your power, at least.

Yikes.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.