With humor and passion, Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil writes about the urgency of protecting Indigenous languages, given that fully half the world’s languages are expected to go extinct within the next 100 years. “This Mouth is Mine” is a triumph.

Welcome to Mexico Well-Read!

I am delighted to be reviewing books about Mexico, this infinitely fascinating, inspiring, gorgeous, sometimes frustrating country we all love. I hope you’ll join me here each month to discover your next great read. I’ll cover fiction and nonfiction on a wide variety of topics, by Mexican and international authors. Books available in English that came out in the last couple of years as well as brand-new releases and forthcoming titles.

I’m particularly on the lookout for underappreciated gems that more MND readers should know about, so please feel free to send suggestions in the comments.

A little about me, Ann Marie Jackson, your trusty guide: I am a book editor with a boutique editorial agency based in San Miguel de Allende, grateful for the amazing privilege of leading a literary life in Mexico. I work with traditional publishers, hybrid presses and indie authors. My own award-winning novel, “The Broken Hummingbird,” is set in San Miguel, where I’ve lived since 2012. And, of course, I am a voracious reader, especially of all things Mexico.

‘This Mouth is Mine’ by Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil

With great wit and enormous charm, Gil has done the seemingly impossible: She’s made a book about topics as potentially grim as the death of languages and systematic discrimination against speakers of Indigenous languages an extremely enjoyable read. With vivid anecdotes, approachable prose and a sense of humor, she invites us to care about the vibrancy of Indigenous languages and the people who speak them. It is in all our interests to advocate for a future in which a diversity of language and culture is celebrated rather than homogenized.

As The Times Literary Supplement put it, “‘This Mouth is Mine’ is an important reminder that the linguistic is political and that linguistic discrimination tends to intersect with racism. [The essays show that] Indigenous languages are modern languages too, as suitable for writing rock lyrics, tweeting jokes, or explaining quantum physics as Spanish and English.”

Gil is a leading defender of linguistic rights who develops educational materials in indigenous languages and documents languages at risk of disappearance. She has also co-presented with Gael García Bernal a documentary series about environmental issues in Mexico.

Half of the world’s languages will die

UNESCO predicts that within the next 100 years, an astounding half of the 6,000 languages currently spoken in the world will go extinct. The University of Hawaii’s Catalogue of Endangered Languages reports that every three months, a language dies somewhere in the world, and the rate will only increase.

As Gil points out, “Never before in history has this happened. Never before have so many languages died out. Why are they dying now?”

The answer, she believes, lies in the fact that 300 years ago, the world was carved up into 200 nation states, and “in order to construct internal homogeneity, a single language was assigned value as the language of the state. [Other] languages were discriminated against and suppressed.”

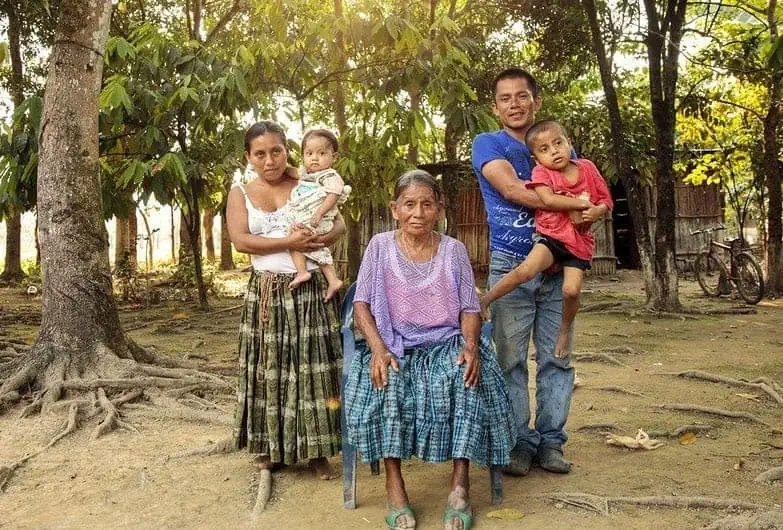

In Mexico’s case, in 1820, when the Mexican nation was established 300 years after the Spanish conquest, 65% of the population spoke an Indigenous language. Today, Gil notes, “Only 6.5% are speakers of an Indigenous language, while Spanish has become dominant. Two hundred years ago, our languages were majority languages: Nahuatl, Maya, Mayo, Tepehua, Tepehuán, Mixe, and all other indigenous languages.”

“Did we suddenly decide to abandon our languages? That’s not what happened. There was a process, driven by government policy, that devalued our languages in favor of just one, Spanish. For our languages to disappear, our ancestors had to endure beatings, reprimands and discrimination for speaking their mother tongues.”

Today, there are many misunderstandings about Mexico’s Indigenous languages — for example, that they are only oral. As Gil explains, “There is evidence of writing on stone, on codices, and a long colonial tradition in the Latin script that dwindled and almost disappeared with Independence, when the government stopped accepting Indigenous language texts.

“Now they’re starting to be written again … There are even languages such as Isthmus Zapotec that had important publications throughout the whole of the twentieth century… writing in Zapotec has an almost uninterrupted written tradition dating back to 500 B.C.”

Defending Indigenous languages today

The accelerated, unprecedented loss of world languages should get more attention because language loss is a key indicator in the well-being of Indigenous peoples. Gil sees reasons for hope, however, in the successes of language activists in various parts of the world.

The Hawaiian language, for example, was at high risk of disappearing, but recently the number of speakers has grown dramatically. Gil credits the fact that “It’s [now] possible to go all the way through from preschool to university studying in Hawaiian.”

“Similarly, in New Zealand, Maori language nests have created new speakers,” she said. And there are other examples. Gil believes that if new generations are to learn at-risk languages, extensive activist efforts such as these are required.

“I believe the movement [in Mexico] to support literature in languages other than Spanish will be greatly enriched if publishers, festivals, fairs, bookshops and readers were to open up to the great diversity of languages and poetics that currently exists — all on the same level, all complex and equal,” Gil said. “Though that might seem an impossible utopia, the state of things is gradually changing.

“The [National Autonomous University of Mexico], for example, organizes the Carlos Montemayor Languages of America Poetry Festival, where it’s possible to hear creators in Zapotec, Portuguese and Mixtec speak in the same forum. Which should be the norm.”

Being bilingual is not the same as being bilingual

In one anecdote, Gil recalls visiting Mexico City for the first time and being delighted by all the ads for bilingual schools and jobs; with a child’s naivete, she assumed that Nahuatl must be highly valued in the capital. She quickly learned that is not the case — only English carries a premium.

“If you were a teacher, speaking an Indigenous language implied having a lower salary and less prestige within the education system. To put it simply, I came to understand that being bilingual is not the same as being bilingual.”

Gil writes passionately about the connections between defending Indigenous territories and Indigenous languages.

“In the movement to recognize Indigenous rights, we’re proud of the ways we resist but still wish we didn’t have to. Resistance implies the existence of an aggression. Resistance,” she acknowledges, “is exhausting.”

Ann Marie Jackson, author of “The Broken Hummingbird,” welcomes you to Mexico Well-Read. Photo by Jessica Patterson.

Join the conversation about ‘This Mouth is Mine’

Once you’ve read it, feel free to share in the comments below the insights you drew from this thought-provoking book, as well as your suggestions of recent (published within the last two years) and forthcoming titles you’d like to see me review.

Ann Marie Jackson is a book editor and the award-winning author of “The Broken Hummingbird.” She lives in San Miguel de Allende and can be reached through her website: annmariejacksonauthor.com.