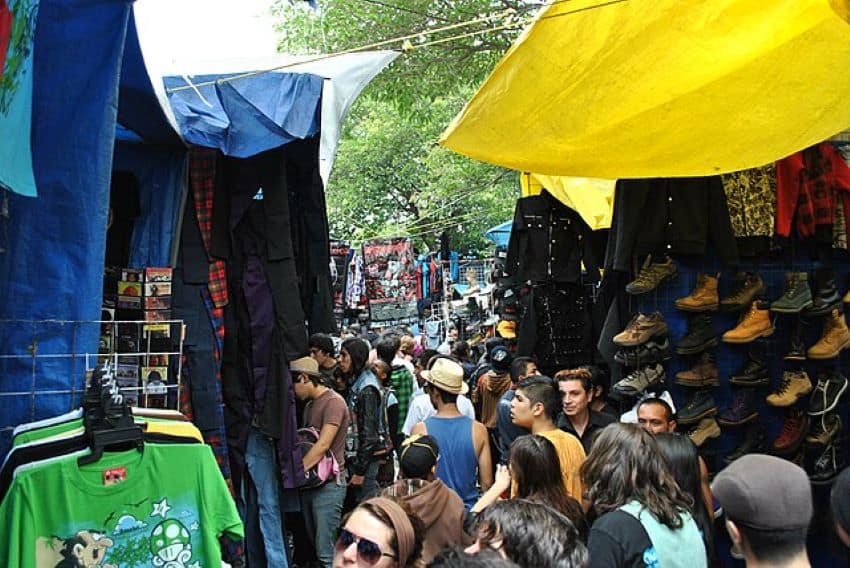

Tianguis can be found throughout Mexico and can be a great way to spend a day shopping, sampling local cuisine or just wandering around taking in the hustle and bustle. A myriad of products can be found in tianguis: handmade crafts that add Mexican flair to your home like straw hats and baskets, blankets and bedspreads, rugs and wall hangings, colorful placemats and pottery for your kitchen or that perfect molcajete you’ve been looking for. You’ll also find mountains of fresh fruit and vegetables, prepared foods and homemade pantry items like jams, salsas and honey. You might just find that item that you didn’t realize you couldn’t live without.

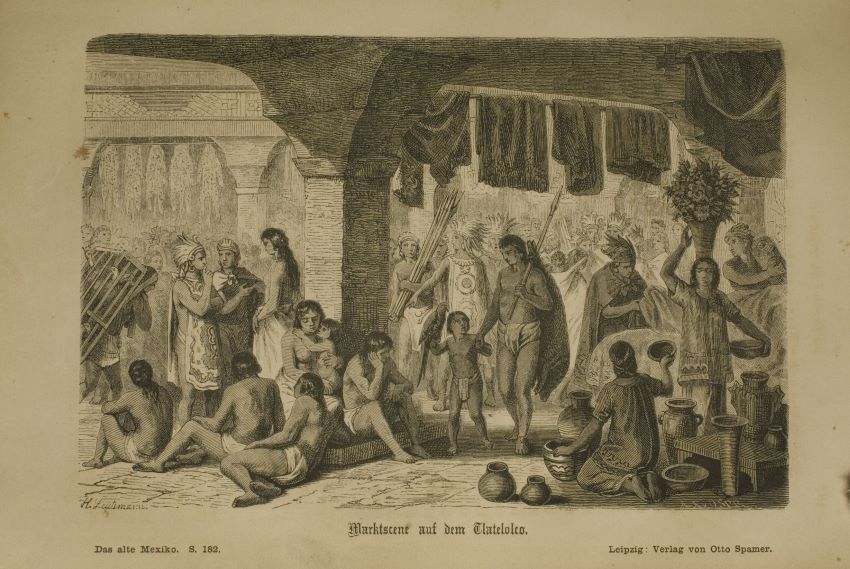

Modern-day tianguis — the word comes from the Nahuatl “tianguitztli,” or market — evolved from Mesoamerican markets, one of which was the Tlatelolco market, located just north of Tenochtitlán, in what is now Mexico City. The tianguis of Tlatelolco is considered the best example of this kind of market in Mesoamerica and its remains can be seen in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, where researchers are still making archaeological discoveries.

The founding of Tlatelolco

Tlatelolco was founded in 1337 by a group of dissident Mexica who broke away from Tenochtitlán to form their own city-state on an islet north of Tenochtitlán. It was a complex commercial network that provided food and other products to the Mexica Empire.

Most of what we know about daily life in Tlatelolco comes from archaeological excavations and the writings of Spanish chronicler Bernal Diáz del Castillo, who first visited Tlatelolco shortly after arriving in Tenochtitlán in 1519. Diáz chronicled his visit in his book “The Conquest of New Spain”: “We arrived at the great plaza, which is called the Tlatelolco, as we had not seen anything like that, we were amazed at the multitude of people and merchandise that was there and the great concert and regiment that they had in everything… each type of merchandise was by itself, and they had their seats located and marked.”

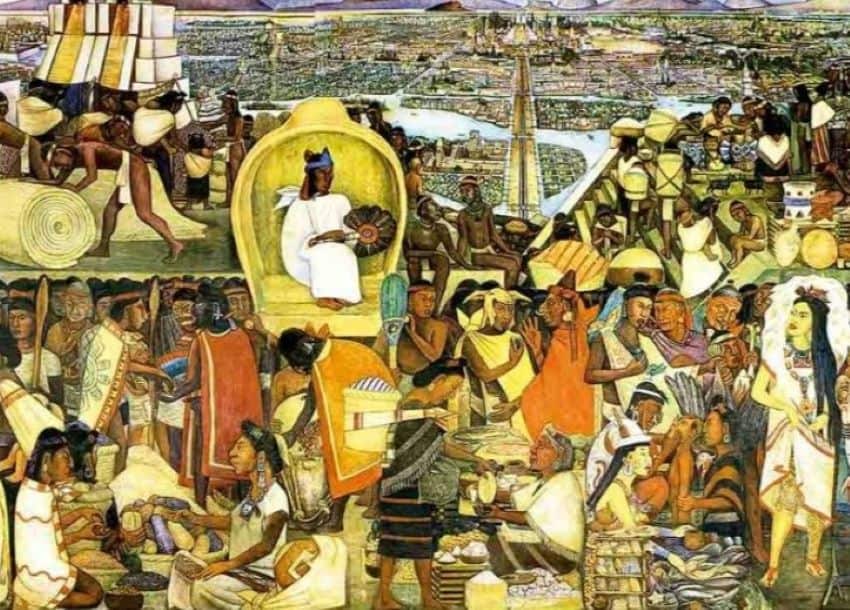

Hernan Cortés, who also visited the market, estimated that approximately 60,000 people came to the plaza daily to exchange products and it was “twice as large as the city of Salamanca.”

Merchants and tamemes (porters) delivered their products through a vast network of land routes and countless canoe trips, many coming from the Gulf of Mexico and other distant locations. Arcades surrounded the market, which was highly organized into an orchestrated concert of barter. Sections were well-defined by aisles and each section had a designated product type. Each merchant had a seat and space on the floor to display their products and begin the day of bartering.

Products and services of Mesoamerican markets

One section contained fresh food products typical of meals consumed in the Valley of Mexico: corn, avocados, pumpkin, tomatoes, a variety of chilis, beans, various seeds like chia and cocoa, chili peppers, legumes and dried fruit. Another aisle displayed wild turkeys, quail, pigeons and ducks. One section was devoted to deer, quails, dogs, hares, turkeys, rabbits, turtles, iguanas, snakes and insects like ants and grasshoppers. There was an aisle that contained freshwater fish, and one for sweeteners like bee and maguey honey traditionally used in cocoa drinks.

One section was reserved for household goods: clay utensils, metates, molcajetes, knives, blankets, mats, baskets, clothing, clay vessels of every size and coarse fabric. There was a section for animal skins, bones, sponges, snails, firewood, charcoal, stone pigments and lime.

Local products were separated into one section and products that were brought from other parts of Mexico were displayed in a different section. High-value items for the Mexica elite were displayed separately from the other products. These items included featherwork, stone goods, finely woven cotton blankets and Cholula pottery.

Like the tianguis of today, there was a section for personal services. Cortés reported that visitors could get their hair washed and cut. There was also an area occupied by herbalists, who prepared herbs and roots as ointments and syrups used to cure disease. Visitors to Tlatelolco could also find prepared foods in one area including corn and cocoa atole, cooked fish, tortillas, tamales and various stews.

According to Diáz, Tlatelolco housed an abundance of slaves, called tlacotin, who could be purchased to be offered to the gods in sacrificial rituals, although some historians believe the slaves were service providers. Diego Durán, a Dominican friar and author of “The History of the Indies of New Spain,” wrote that the market also provided an opportunity for slaves to escape: if a slave managed to get away and stepped on animal feces, he could claim his freedom.

A tightly regulated market

The Tlatelolca exercised a high degree of order and discipline over their market. Chambers of justice were clearly delineated by rectangular buildings with arcade walkways. Judges were chosen to regulate and monitor the commercial activities of the market to ensure good exchange practices and regulate the prices of goods and services. They were also responsible for resolving any disputes that might arise. Wandering bailiffs maintained order organizing merchants, aisles and sections according to the type of merchandise or service being offered.

Diáz wrote that the Spaniards “were amazed at the amount of people and products [the market] contained, and the order and control that was maintained.” All commerce at the market was conducted through a system of bartering and exchange of goods and was tightly controlled by the judges and bailiffs. It was a very complex and cosmopolitan market that served the dietary, cultural and religious needs of the Valley of Mexico.

Tlatelolco became the most active and eventually the largest market in central Mexico and Central America. After the fall of Tenochtitlán, Tlatelolco was almost completely destroyed. The market was abandoned, and the merchants began their commercial trade in Tepito in the Merced area — an independent trading tradition that still exists in the Tepito neighborhood today.

Tlatelolco and the tianguis of today

Tianguis were designed to provide products to middle and lower-class Mexica. Tlatelolco provided almost all the products consumed in Tenochtitlan and was the commercial center for the entire region.

Most contemporary tianguis have the same purpose and are only open on weekends. Every tianguis varies depending on the region and products are based on the local food, sweets and handicrafts produced in that region. The most famous tianguis in Mexico City is the Tianguis Cultural del Chopo, where visitors can find handmade crafts, jewelry, music and food. If you haven’t been before, a tianguis is a fascinating way to spend the day, soak up this cultural tradition and support local artisans.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer, and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.com