For at least 300 years, the rumors have persisted. Beneath the streets of Guadalajara lies a vast network of tunnels that connect important buildings in the city, from churches and convents to mansions and monuments, chapels and cemeteries. The tunnels are wide and high enough to accommodate horses and even carriages, it’s said.

Supposedly, the Father of the Revolution, Miguel Hidalgo, even used these tunnels to escape his enemies and Benito Juárez found them handy for getting around the city unnoticed. People still talk about the story of a group of priests who were in the cathedral one minute and then suddenly appeared at the governor’s palace for a meeting. When the meeting was over, it was said, they reappeared at the cathedral, having never been seen upon the city streets.

Friar Buzeta to the rescue

An investigation into these mysteries, carried out in 2013 by Dr. Alicia Torres Rodríguez of the University of Guadalajara, revealed the truth behind the rumors. The legendary “tunnels of Guadalajara” are actually galerías filtrantes, underground aqueducts constructed during the colonial period to direct potable water into the city.

Most of them, says Torres, “owe their origin to a Franciscan Friar named Pedro Buzeta.”

In the 1700s, she says, the city was desperately short of water. Word reached the city fathers that a Spanish friar had recently succeeded admirably in bringing water to the city of Veracruz, and they sent for him.

Buzeta soon determined that water could be found on the north and southwestern skirts of Guadalajara and that the best way to carry it into the city was not via aqueducts but through a gravity-based filtration gallery, which employs 3,000-year-old technology originating in Persia.

This underground aqueduct is widely known by its Arabic name: qanat.

How to dig a qanat

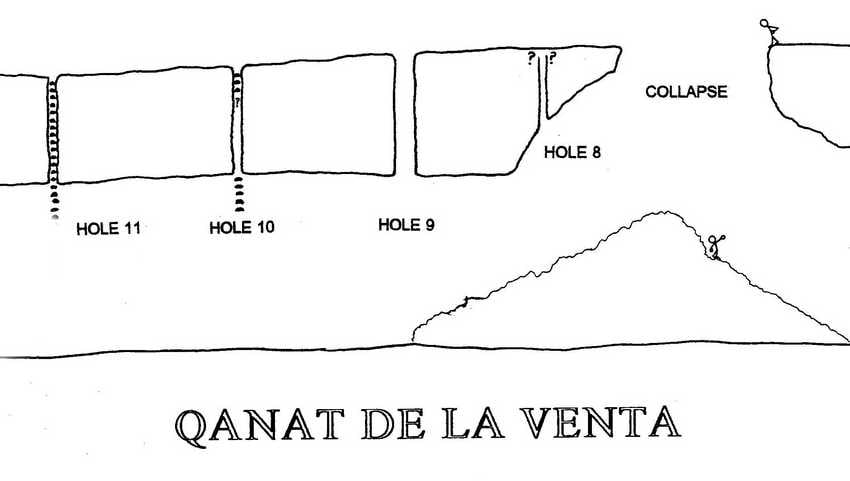

To dig a qanat, technical experts called muqannis trace a straight line above ground between a well and a distant site where water is needed. At regular intervals along this line, workers dig holes less than a meter wide, down to an exact depth — different for each hole.

Next, all the holes are joined together underground, resulting in a tunnel perhaps 2 meters high and 1 meter wide, with a downward slope of less than 2 degrees.

The final step is to connect the tunnel to the water well. This is tricky indeed, and if it’s not done exactly right, the person making the connection may not survive. Once water is slowly moving through the filtration gallery, all the access holes are covered with flat rocks to keep the qanat clean and to reduce evaporation.

This technology proved very popular and was adapted by the Arabs, the Romans, the Chinese and the Spaniards, who brought it to Mexico. Most qanats are less than five kilometers long, but some are over 70 kilometers in length.

‘This is not a cave!’: Guadalajara’s hidden qanats

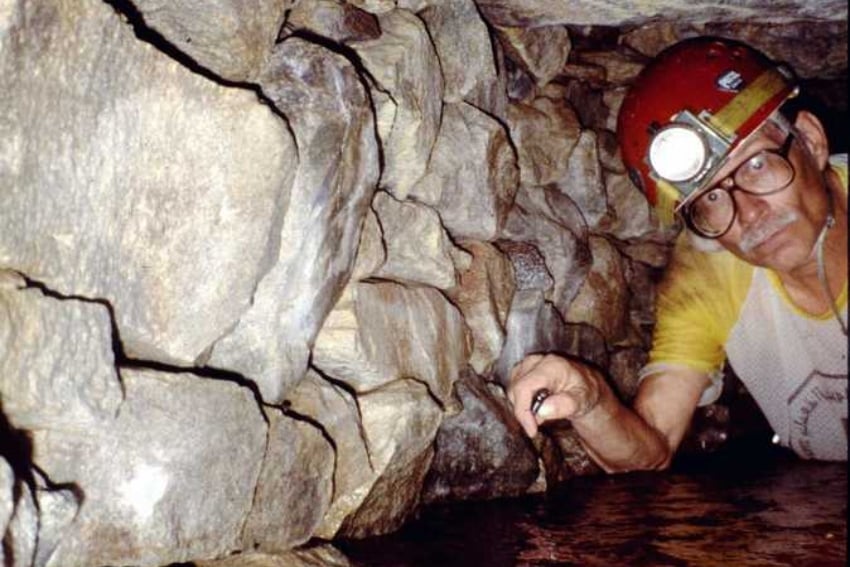

For many years, I was a cave explorer in western Mexico, which led to my first encounter with a qanat in the hills above the little town of La Venta del Astillero, located just west of Guadalajara.

It seemed at first that our group of speleologists had discovered a very long, very curious cave with 70 small roof entrances in a straight line, spaced 11 meters apart. Those holes produced beams of light that we found both picturesque and useful.

But when we invited archaeologist Phil Weigand to take a look at it, he immediately said: “John, this is not a cave; it’s a qanat!”

Once we recognized the pattern, we found several more qanats in the area. One of these finds occurred after a request from the director of a tree farm at the northwest end of Guadalajara.

‘A request like this is what cavers live for’

“There’s a kind of well on our property with iron rungs that go down to a locked gate. Behind the gate, there’s a long tunnel. Would you please come and tell us what this is?”

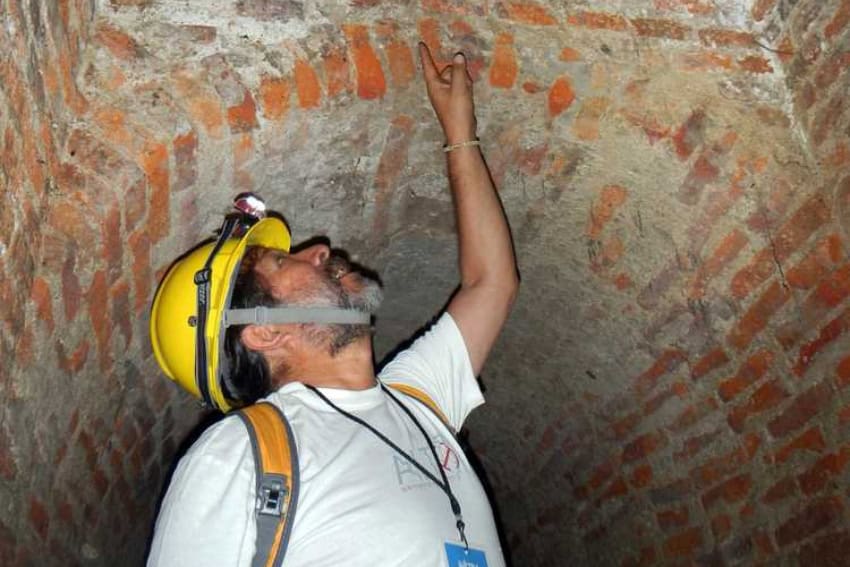

A request like this is what cavers live for. We arrived with lights, helmets and survey gear.

“Inside that tunnel, did you see any small holes in the roof?” I asked the director.

“No, I didn’t,” he said — which surprised me.

We clambered down the rungs, the tree farm director unlocked the gate and we found ourselves at the start of a long, straight tunnel just over 1 meter wide and almost 2 meters high— not quite spacious enough for a carriage but perhaps enough for a small horse.

The walls and the curved roof were made of brick and looked in good condition. Water was running along a channel on the right.

“This looks suspiciously like a qanat, and a very elegant one at that,” I told him.

We began our survey, and exactly 100 meters from our starting point, we found an opening above our heads: a shaft with footholds, leading up to a kind of manhole cover with sunlight streaming through a small hole.

Every 100 meters, there was a shaft, indicating that this was, indeed, a qanat.

After 300 meters, our passage emptied into a big, round pool. On the other side, we could see tunnels similar to the one we were in. They led off to other places.

By now, it was clear: We were inside the network of qanats built under the supervision, or at least inspiration, of Friar Buzeta.

20 kilometers of crumbling qanats

By the beginning of the 20th century, Dr. Torres estimates, Guadalajara was supplied by nine lines of filtration galleries with a total length of up to 20 kilometers.

Amazingly, these qanats, built between 1731 and 1895, still supply a substantial amount of water to the city.

Unfortunately, no one knows exactly where they are located. “They have been abandoned,” says Torres, “and they are beginning to crumble.”

Bear that in mind in case someone invites you on an underground tour of Guadalajara.

John Pint has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.