English speakers constantly use words borrowed from Latin, Greek, French, German, Spanish and plenty of other languages, but did you know we even have a few words from Nahuatl?

This indigenous language famously spoken by the pre-Hispanic Mexica is still spoken today by around 1.5 million people in Mexico. It once served as a lingua franca among ancient peoples in Mexico and Central America. Curiously, it appears to have originated in what is now the southwestern United States, thereafter slowly spreading southwards.

Because it’s still a living language, English speakers from all over the world have had a chance to interact with Mexico throughout modern history and thus borrow various words from Nahuatl, words like:

- chocolate

- tomato

- coyote

- tamales

- peyote

- guacamole

- mezcal

- shack

“Shack?” Believe it or not etymologist David Gold traces this word back to the Nahuatl word xacalli, (note that this x should be pronounced “sh”), also spelled jacalli, meaning “hut with a straw roof.”

He says settlers on the Great Plains of the United States couldn’t use wood for their homes and learned the building techniques of the local Native Americans who spoke Uto-Aztecan languages and used the word xacalli. Audubon’s Western Journal says, “The ranchos are forlorn ‘jacals,’ sheds covered with skins and rushes and plastered with mud.”

If a few Nahuatl words like “chocolate” and “tomato” have found their way into English, far more have inserted themselves into Mexican Spanish.

Read the following. Can you understand what it’s all about?

“While he was in the tianguis, Nacho bought cacahuates for his pet tlacuache. As long as he was there, he looked for atole but couldn’t find any, so he settled for tejuino.”

“I want a popote with it,” he said, and when he didn’t get one, he became angry.

Replied the tejuino maker: “Por favor, cuate, stop this mitote and I’ll give you your popote!”

Easy to follow? If not, here’s a glossary of the words that come from Nahuatl:

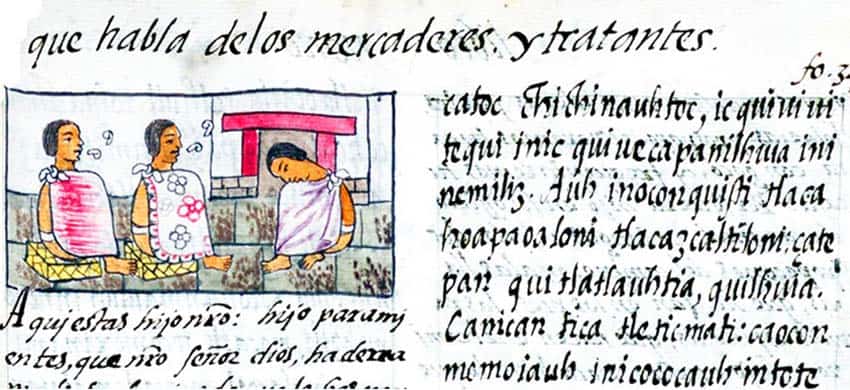

- Tianguis: from the Nahuatl tianquiz(tli), or a street market. If a tianguis is enclosed, it will be called a mercado.

- Cacahuate: this means “peanut.” The ancient Mexica used to refer to a ground nut as a tlacáhuatl or “earth cocoa-bean.”

- Tlacuache: a tlacuache is a possum. This word comes From tlacuatzin, meaning “little fire-eater.”

How is a possum a fire-eater? Well, in pre-Hispanic mythology, the tlacuache stole fire from the gods (grabbing a firebrand with his tail) and gave it to men. And that’s why the tail of a possum is hairless! - Atole: a thick drink popular in Mexico made from corn flour and water, sweetened with piloncillo (brown cane sugar) and flavored with cinnamon, vanilla and maybe chocolate. Atole is what you drink right before you hit the sack.

- Tejuino: a tart, nonalcoholic beer made from sprouted corn still popular in parts of Mexico. The ancient Nahua viewed it as the “drink of the gods.” If you drink it regularly, they say, it will replace the pathogenic bacteria in your colon with probiotics.

- Popote: this word, meaning “drinking straw,” is derived from the Nahuatl popotli, referring to the hollow reeds which grew all around the ancient city of Tenochtitlán.

- Cuate: this word said to come from Nahuatl means “twin.” Today it is used much like “buddy” or “dude.”

- Mitote: this may have originally referred to the dancing and drinking that went on at ceremonial centers in pre-Hispanic Mexico. In modern times it means “a mess” or “chaos.” Armar un mitote is to make a fuss.

Ready for more? The following paragraph contains a few more Nahuatl words ensconced in the ordinary vocabulary of many Mexicans: “A tecolote peacefully slept in a pochote while a zanate danced in the branches of an amate. Down below, seven escuincles played with their canicas…”

- Tecolote: this comes from the Nahuatl word for “owl” and is found in the common Mexican dicho or saying, “Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere.” (“When the owl hoots, the Indian dies.”)

- Pochote: also called a ceiba, this is the silk-cotton tree, considered divine in ancient Mexico because its branches, trunk and roots represented the cosmos’ three levels. Many pochote varieties can be recognized by their trunk’s thick spikes.

- Zanate: this bird is called the great-tailed grackle in English. Legends say it has seven distinct songs, all of which it stole from the sea turtle. It is thought that in these songs you can hear the seven passions: love, hate, fear, courage, joy, sadness and anger.

- Amate: ficus tree, and also paper made in pre-Hispanic times out of the tree’s bark. Still used today by artisans, ancient peoples used it for communication and religious ceremonies. A crumpled piece of amate paper found in the Huitzilapa shaft tomb in Jalisco dates back to the year A.D. 70.

- Escuincle: this is a short form of xoloitzcuintle, the Mexican hairless dog breed. Today, the derivative escuincles refers to children. This is not necessarily pejorative, as xolos were considered protectors from evil spirits and the guides who take our souls to the next life.

- Canica: This word means “marble,” as in the glass balls kids play with. The word supposedly comes from the Nahuatl expression Ca, nican nican! meaning: “This is mine right here!” which you would shout if you thought your marble was the winner.

- Petatearse: a petate is a mat woven from reeds or palm fronds. It was also used to roll up a corpse for burial. From this comes the verb petatearse. So, se petateó means something like: “He kicked the bucket.”

- Titipuchal: a great quantity of people or things. So, this sentence — “Mi bisabuelito se petateó por el titipuchal de años” — means: “My great-grandpa died of a superabundance of years.”

Which might sound a bit more chistoso (funnier) like this: “Great-grandpa kicked the bucket because he was older than the pyramids.”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.