A 1,400-year-old scorpion-shaped effigy mound discovered in the Tehuacán Valley in the state of Puebla might have served as an astronomical observatory, researchers say.

The discovery, disclosed in the University of Cambridge’s Ancient Mesoamerica journal, has been described as “unprecedented.” Effigy mounds — prehistoric earthen mounds shaped like an animal, spirit or other figure — are common in the midwestern United States, but extremely uncommon in Mesoamerica.

Archaeologists came across the mound and plaza complex in 2004 while conducting a survey to document the prehistoric canal systems in the central portion of the Tehuacán Valley, about 160 miles southeast of Mexico City.

The scorpion-shaped mound is strategically placed in the center of the largest preserved prehistoric irrigation system in Mesoamerica, comprising approximately 100 square kilometers of canals that have functioned continuously for more than 4,000 years.

Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), which collaborated on the research, said in a press release that, based on the evidence gathered, the site appears to have been “part of a civic/ceremonial complex possibly used for astronomical observation.”

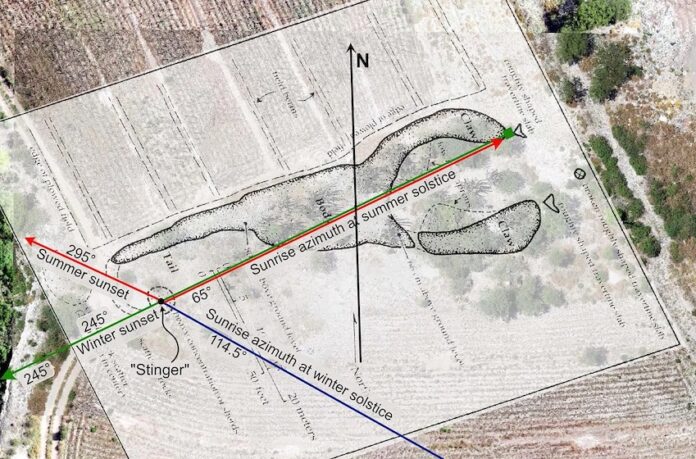

Researchers surmise that the orientation of the scorpion-shaped structure allowed the ancient inhabitants of the Tehuacán Valley to observe exactly when the sun rose over specific points of the mound during the solstices, enabling them to optimize their crops in one of Mexico’s driest regions.

If it was used for solar observation, researchers said it could provide “an insight into the integration of calendrical ritual with the surrounding complex system of fields and irrigation canals.”

The scorpion mound is 62.5 meters (205 feet) long, its body, head and pincers extending in an east-northeast orientation. It is 13.2 meters (43 feet) wide by 80 centimeters (31 inches) high and the space between the pincers is 22.1 meters (72.5 feet).

In Mesoamerican cosmogony, the scorpion was a prominent celestial deity associated with Venus, the morning star, which in turn was linked to Tláloc and Quetzalcóatl, deities of rain and wind, respectively.

Also uncovered at the site — within the tail and stinger of the scorpion — were large quantities of ceramics, including surface-decorated and polychromes, indicating a Late Classic and Postclassic occupation.

The discovery of the ceramics not only revealed the mound’s age, but also hinted at its social and economic significance.

The ceramic diversity — the materials correspond to ceramics from Cholula, the Mixteca region of Oaxaca and the Gulf of Mexico — suggests the site was a fundamental part of the valley’s commercial and social networks with the main power centers of Mesoamerica.

A modern offering was found on top of the head, according to INAH. The offering consisted of two light and dark brown tripod vessels containing tobacco and chili peppers, suggesting that the site continues to be part of the cultural practices of the present-day population.

With reports from Archaeology News and El Sol de Puebla