Just outside the city of Querétaro lies Escolásticas, a town where the art of stonework is still passed down like a school lesson, from master sculptors to apprentices.

On a friend’s recommendation, I visited Canteras Querétaro — one of over 300 local workshops — and quickly saw what set it apart: Amid the dust and towering sculptures of archangels, columns and fountains, I met Hugo Uribe, a young engineer, entrepreneur and sculptor blending tradition with technology.

Like the cantera, or quarry stone, his team shapes, Hugo’s story is built on resilience, history and a drive to innovate.

This is the third installment of Hecho en México, a series celebrating the people behind Mexico’s vibrant creative traditions. From weavers and painters to entrepreneurial stoneworkers like Hugo, we explore the traditions, challenges and triumphs that drive Mexico’s artisans to share their talent while preserving Mexico’s rich artistic heritage.

From engineer to artisan entrepreneur

From an early age, Hugo was destined to build more than stone sculptures.

While his father and uncle carved cantera in Toluca, young Hugo played at being a businessman. In his uncle’s workshop, he’d collect payments from real customers and pretend to invest the money, dreaming up profits and growth just for fun.

Childhood games evolved into a more technical path when, in college, he chose to study metrology, the engineering science of measurement. After graduation, he landed a well-paying job at Stellantis, one of the world’s largest automakers.

“I didn’t know what I wanted,” Hugo admitted. “I was always good at math and physics, and I just knew I wanted something challenging. Easy things put me to sleep.”

Though short on experience, he earned a leadership role in the corporate world by promising discipline, responsibility and honesty. But the so-called dream job didn’t satisfy his entrepreneurial spirit.

“I kept thinking, I have so many projects, so many dreams. I wanted to help my mom, my dad. It was a good salary, enough for me, but not enough to help others. I’ve always loved helping people, even since kindergarten.”

Hugo ended up staying at Stellantis for five years. Meanwhile, his parents moved back to his hometown of Escolásticas, a village of 3,000 where, since the 1950s, residents have mastered the art of cantera sculpting at every stage — from quarrying locally to carving to finishing. With over 60% of the population working in the artisan trade, driving into Escolásticas feels like stepping into an open-air sculpture museum.

Hugo learned the craft of cantera from his father and uncle, sanding and polishing stone by the time he was six. The work was in his blood, and he pursued it as a hobby, even during his corporate years.

“When I work with cantera, I never feel the passing of time. I love sculpting, but I love business more — meeting people, building relationships. That’s what drives me.”

Hugo followed his entrepreneurial calling and built a side hustle, selling cantera online on behalf of workshops in Escolásticas. Many of his deals were done in the middle of the night as sleepless customers browsed his products.

“My dreams kept me awake,” he said. “I’d spend hours running numbers, testing ideas. At first, I kept it quiet. I didn’t want people to think I was doing it just because of my dad.”

But the business grew. He tested workshops by giving the same order to four and comparing their quality, reliability and timelines. He narrowed it down to a few he could trust and began placing consistent orders.

In 2020, when the pandemic hit and he was offered a severance package from Stellantis, the choice was clear: It was time to go all in.

Hugo’s family studio is located in his hometown of Escolásticas, a village in Querétaro known as “The Land of Cantera” due to the high number of cantera studios there.

Blending tradition with technology

Taking a bold leap of faith, Hugo founded Canteras Querétaro, now one of the region’s most respected workshops. At first, he partnered with local sculptors while he managed sales and marketing. But as the business grew, misaligned visions caused those early partnerships to dissolve.

So he turned to the two people he trusted most: his brother José, a systems engineer with a sharp eye for automation, and his father, a master craftsman with decades of cantera experience. Together, they built something unique: a family-run workshop blending tradition with innovation.

As demand surged during the pandemic, especially with more people investing in home renovations, the team needed to adapt.

“There was little workforce, sales were high and our processes were too slow,” Hugo explained. “And the truth is, fewer people want to do this kind of work.”

Curious about CNC (computer-controlled cutting) technology, Hugo heard about a new machine arriving from China. When the owner wouldn’t let him use it, Hugo offered to fix a problem with the machine, something even expert technicians from Monterrey couldn’t solve.

“‘I’ll solve it,’ I told the owner,” he said. “He was skeptical, but for me, there was never such a thing as an obstacle. If you don’t take the leap, you don’t learn.”

So he and José got to work, studying manuals and rewriting code. Through trial and error, they finally got it running. Impressed, the owner let them use it — and asked Hugo to train his team.

That experience sparked a bigger idea: With some of his severance pay, Hugo traveled to Guadalajara and ordered two CNC machines, despite only having enough money for one.

“We’ll figure it out,” he told his brother.

They sold two more machines for the manufacturer, used the commission toward their own, and secured a loan for the rest that they owed the manufacturer.

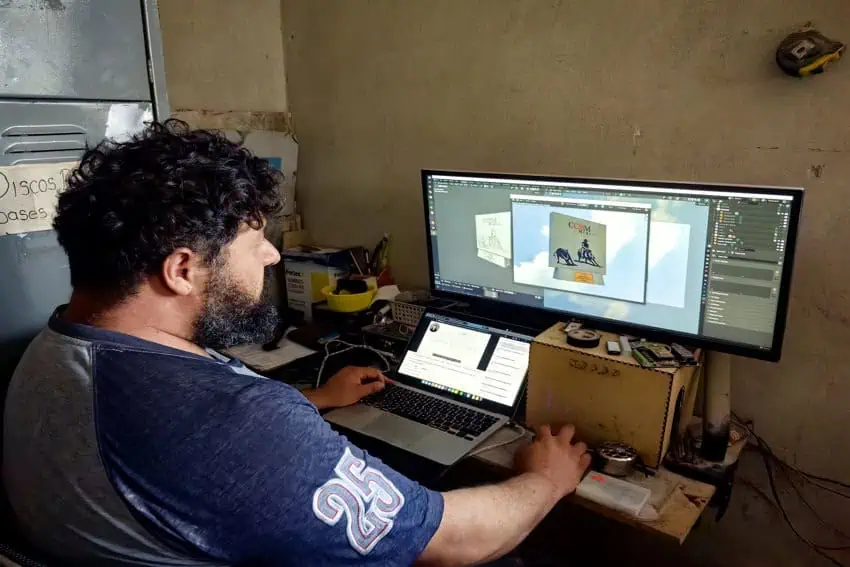

Today, those machines are essential tools in their workshop, alongside newer additions like 3-D printers and digital modeling — thanks to José’s tech expertise. But, as Hugo says, the soul of the work is still human.

“CNC can take a design maybe 40–60% of the way,” he explained. “The rest is craftsmanship — polishing, finishing, adding the detail that gives a piece life.”

For example, they’re currently producing a five-meter mural of galloping horses and a series of San Miguel Arcángel (St. Michael) sculptures. The machines handle the initial form, but it’s human hands (often his father’s) that complete the artistry.

“I’m convinced we shouldn’t lose the tradition of handcrafting,” Hugo told me. “It’s something beautiful, it’s art. But if you want to grow and survive, you simply can’t do everything by hand.”

The team’s work hasn’t gone unnoticed. Canteras Querétaro is currently bidding on a luxury hotel project in Mexico City, poised to be one of the most exclusive in the country.

The team has also earned top honors at local and regional competitions, including a recent cantera sculpture contest that brought together workshops from across the state. Hugo submitted a personal piece he carved in his spare time — a woman that symbolized freedom and abundance, qualities he sees reflected in his craft and his life.

But for Hugo, these milestones are just the beginning. His next big goal is to expand the workshop’s reach by opening dedicated cantera supply stores in Mexico and abroad, spaces that offer not only carved pieces but also raw stone, tools and materials like sealants and moldings.

“Sourcing cantera can be slow and fragmented,” he explained. “If someone urgently needs a specific molding for a construction project, I want them to be able to walk into a store and find it ready to go.”

Beyond business, Hugo is committed to creating opportunity. Canteras Querétaro partners with Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro, a government program that connects unemployed youth (ages 18-29) with yearlong apprenticeships and paid training.

Hugo also mentors many of the young people who come through the workshop, sharing not just technique, but life lessons. He speaks openly about living free of addictions, a challenge that affects many in the region, and emphasizes the importance of knowing what you want.

“If you don’t know what you want in life, life will give you whatever, and you won’t be satisfied or in the right place, with the right people, doing what truly matters.”

His advice: Start by asking yourself what you really want.

A legacy in the making

Hugo attributes the success of his business to prioritizing quality, investing more time and money than competitors to perfect details, especially in realistic features like faces.

On the personal front, Hugo credits his achievements to fearlessness, a willingness to try anything, and, above all, the support of his family.

He speaks with deep respect for his parents: his father, from whom he learned the value of hard work, and his mother, who championed education. Together, they instilled values that now shape the family business: growth over jealousy, long-term impact over short-term gain.

“We don’t spend just to spend,” he said. “There’s a dream behind it. It’s a seed we planted. Right now, it’s a medium-sized tree, but the more we water it, the more people it will feed and shade. That’s the goal: to grow a team and through that, be able to help others.”

To learn more about Hugo and the work of Canteras Querétaro, visit www.canterasqro.com or reach out to the team directly at +52 442 675 1945.

Hecho en México is a series written by Karla Parra, a Mexican-American writer born and raised in Mexico. While working on her memoir, Karla writes on Substack about home, creativity, and identity. She also works with the team behind the annual San Miguel Writers’ Conference. You can find her on Instagram @karlaexploradora.