The internet is alive with UFO reports at the moment, the excitement sparked by a comet identified as 3I/ATLAS. Comets are not uncommon visitors to our solar system, but this is a rare type. Its speed, its path and its composition identify it as an object that is not circling within our solar system, but racing through it.

It is only the third such object ever observed and is believed to have originated from close to the galactic center of the Milky Way. When the first photographs arrived, its unusual cigar-like shape threw UFO believers into a frenzy, convinced that this was a spaceship and that we are just a few months away from making contact with an alien civilization.

Early photos of astronomical phenomena

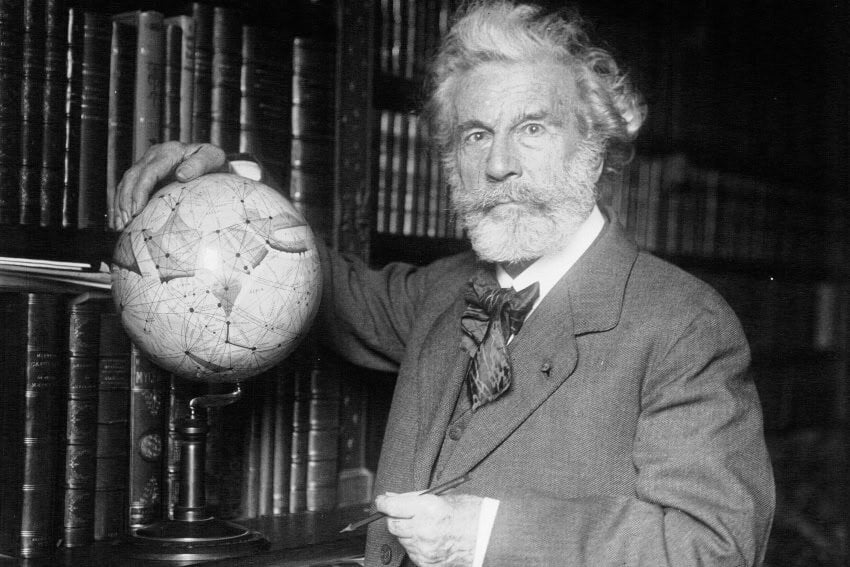

People might be surprised to learn that the first photograph of a comet was probably taken here in Mexico, a remarkable feat completed by José Árbol y Bonilla.

Born in Zacatecas in February 1853, Árbol studied topographical engineering and was sent on a scholarship to the Escuela de Minas in Mexico City. A bright young man, he completed the three-year course in one year and then returned home to become a teacher at the García Literary Institute, where he continued his own studies.

After developing an interest in photography, he moved to Paris in 1879, taking the opportunity to study the new skill of celestial photography, the photography of astronomical objects, celestial events or areas of the night sky.

The first attempts at celestial photography are credited to Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, a French scientist, artist and photographer recognized today for his invention of the daguerreotype photographic process. This involved polishing a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish, then treating it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive.

Evolution of photographic techniques

Taking photos in this way required a long exposure, so while a skilled artist with a patient model could produce impressive portraits, any attempt to capture the sky in a photo was limited to the brightest of objects — the moon or the sun. Even then, the results were hardly impressive.

The invention of the gelatin silver “dry plate” process, attributed to Richard Leach Maddox, improved photography considerably, making it more accessible and far more versatile. In 1880, Henry Draper used this new process with a refracting telescope to picture the Orion Nebula. This required a 51-minute exposure and was a significant breakthrough. Within three years, amateur astronomer Andrew Ainslie Common recorded images of the Orion Nebula that were so clear that they revealed new stars too faint to be seen by the human eye. This was the exciting world that Bonilla entered.

Astronomical observations and photography in Mexico

After Paris, Bonilla returned to Mexico, and when, in December 1882, the State of Zacatecas opened an astronomical observatory, he was the obvious candidate to become its first director. Indeed, it is uncertain — but seems quite likely — that Bonilla had been one of the voices calling for its creation.

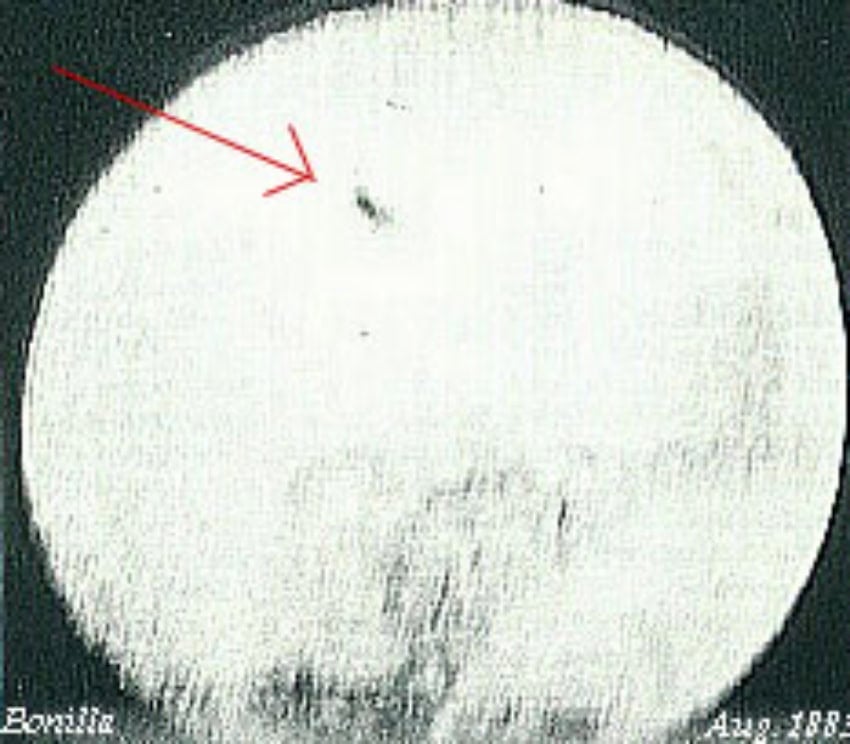

The following year, Bonilla was in the observatory for a routine observation session when he noticed unidentified objects passing across the sun. He telegraphed the observatories in Mexico City and Puebla so that they could also observe this strange event. Working through two days in August, Bonilla counted 447 such objects. He also used the skills he had acquired in Paris to capture several photographs of the event.

Bonilla sees and photographs mysterious objects in the night sky

Bonilla could tell simply by focusing his telescope that these mysterious objects were passing close to Earth, for when he focused on the sun, they blurred, and when he focused on the moon, they became sharper. To his surprise, the other observatories in Mexico had been unable to see them. This might suggest that there was some fault with his telescope, but it could also be another indication that the objects were very close to the Earth: An airplane just taking off is only visible to people close to the runway, but a plane at 30,000 feet can be seen by the entire city.

Bonilla struggled to find a publisher to report his observations, but after two and a half years, Camille Flammarion, whom Bonilla knew from his time in Paris, published an account in the highly prestigious French magazine “L’Astronomie.”

Flammarion was a strange combination of scientist and conspiracy theorist, a man who firmly believed, for example, that there was life on Mars. Even Monsieur Flammarion could not come to any conclusion as to what Bonilla had observed, but he was not particularly supportive, suggesting Bonilla had photographed birds or insects, or that there had been dust on his telescope.

Bonilla’s life afterward

The story slipped from public view, and Bonilla went on to have a successful career — and, we can only hope, a happy life. He toured the United States, England and Northern Europe to visit observatories. At home, he wrote the first modern cosmography text for Mexicans schools, and he located a rare meteorite that had been seen falling to the earth. He supported the local children’s hospice and, in 1911, became director of the National School of Arts and Crafts in Mexico City. He married, had two children, and died in 1920 at the age of 66.

Bonilla’s observations returned to the news in 2011. Along with his photographs, Bonilla had left descriptions of the mysterious objects as “fuzzy” or “misty” in nature. He also referred to them as having “dark tails,” and this caught the attention of Hector Manterola at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Bonilla’s mysterious objects are tentatively identified

Manterola and his team argued for a new possibility: Bonilla had photographed neither a UFO nor geese. What he had seen was the remains of a massive comet that had broken up and fragmented.

The team started with a hypothesis: “Our working hypothesis is that what Bonilla observed in 1883 was a highly fragmented comet, in an approach almost flush to the Earth’s surface.”

Having raised this possibility, the team started their calculations. Although Bonilla’s photographs had done a great deal to draw attention to the sightings, they did not prove particularly useful in the investigation. We are actually uncertain how many plates Bonilla made. He spoke of “several,” and there were at least three. One might have been sent to Paris to be used for the illustrations in “L’Astronomie.” However, it is just as likely that Bonilla sent a high-quality facsimile.

In 1919, Charles Fort, that great collector of weird and wonderful science stories, suggested there was one plate at the Zacatecas University — one with the Zacatecas School of Engineering, and possibly others in Bonilla’s files at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas.

A massive comet and thousands of fragments pass by

Since then, they all seem to have disappeared, and Manterola’s team only had a digitally enhanced copy of the illustration that had appeared in the scientific journal, “L’Astronomie.” This did give some supporting evidence as to the size of the objects captured in this one photo, but mostly, the team worked with Bonilla’s notes and observations. The advantage they had over Bonilla himself was that science now had a much better idea of how a fragmented comet should behave.

As a starting point, they had the important fact that astronomers at observatories in Mexico City and Puebla had not seen the objects. As mentioned above, for the objects to have been visible from Zacatecas but not from other Mexican observatories, they would have had to be very close to the Earth. The team could now put a number to that, calculating a rough distance of 80,000 km, which is much closer than the moon.

Bonilla had also recorded the time each fragment had taken to pass across the sun. Unfortunately, we don’t know what instruments Bonilla used to make these timings. Therefore, we don’t know how accurate they are. However, this data, if accurate, brought the objects to within 600 to 8,000 kilometers of the Earth’s surface.

Terrifying calculations revealed

This, in turn, allowed a calculation to be made for the size of each individual chunk of rock, which the team suggested ranged between 50 and 800 meters wide, very similar in size to the comet that struck at Tunguska in 1908. Bonilla had not spotted one comet but a shower of 447 objects over a period of three hours and 25 minutes. Presuming this rate continued for the whole time the objects were passing, it can be estimated that 3,275 large fragments of rock had rushed past the Earth over 25 hours.

This raised another question. If these had been visible against the sun during the day, they should have put on a dramatic meteorite show during the night. So why didn’t they? One answer to this was that the fragments had passed over an area that was largely ocean or desert and might not have attracted any attention.

With so little data to work with, the team probably never expected to reach a definitive conclusion. What they hoped was that the evidence would support the possibility that Bonilla had seen a fragmented comet. This was indeed the scenario they put forward.

Scientists on the other side of the argument have pointed out that the tightly focused stream of objects is not quite what you might expect — that the lack of sightings of any meteorites that night is not fully explained, and that there is a lack of a candidate comet.

Extinction spared

However, if the National Autonomous University team is correct in their interpretations, then the Earth had a very near miss. Had this debris passed a fraction closer, we might have been bombarded by a string of Tunguska-like events for two days, bringing untold destruction. Ours would be a very different planet today.

There was also the question of the “mother” comet. The speed of the fragments suggests it had only recently broken up. Two comets spotted in 1883 are possible candidates, although it is just as likely that the original comet went unnoticed. It was, however, a giant, an extinction-threatening piece of rock 8.18 times the mass of Halley’s comet.

In 1883, the British were fighting wars in Egypt, and the French in Vietnam. Later in the year, Krakatoa would explode, striking Southeast Asia with a massive tsunami. It is possible that a far greater danger to mankind went completely unnoticed.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life-term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.