As part of an exploration into Mexico’s long and rich history, Mexico News Daily has teamed up with one of the country’s top Maya experts to examine the ancient world that flourished across Mesoamerica.

What we know today as the “Maya area” of Central America encompasses parts of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador — a region popularly called “Mesoamerica.” However, it’s important to note that this is a modern interpretation, and the people who lived there centuries ago definitely did not see things the same way.

The geography of Maya precontact cultures — those that existed before the arrival of the Spanish — is historically divided into three zones: the Northern Lowlands, which cover basically the entirety of the Yucatán Peninsula; the Southern Lowlands, spanning modern-day Chiapas and Tabasco, as well as parts of Guatemala and Honduras; and the Highlands. Mexico’s Maya populations were mostly found in the Highlands, while the Lowlands were occupied by what we now consider to be groups in Guatemala and Belize.

The first Maya peoples

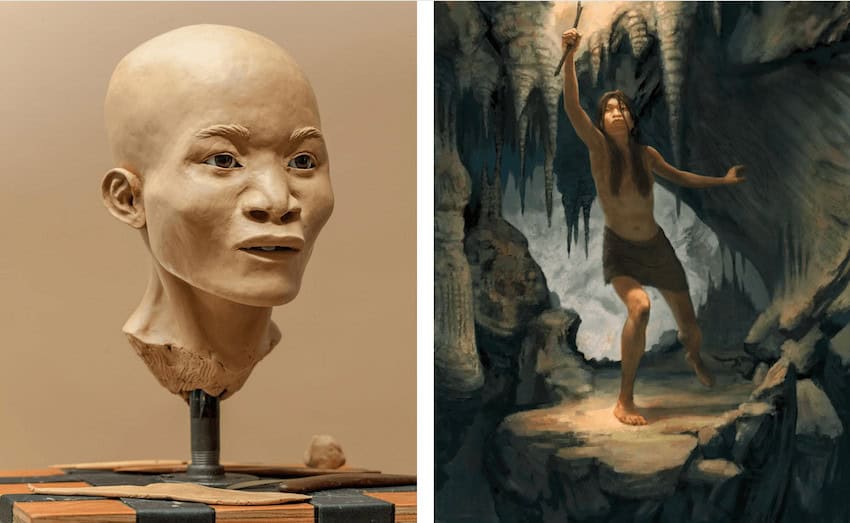

According to current research, the first people to inhabit this territory did so during the Holocene period, around 10,000 B.C. — the current geological era that began after the last Ice Age. One of the most famous finds from this period is the skeleton of a young woman nicknamed Naia, discovered in 2007 in the submerged cave of Hoyo Negro in Quintana Roo, Mexico. She is believed to be about 13,000 years old. Stone tools, along with rock shelters containing cave paintings, are among the other evidence pointing to an early human presence in the region.

Only with the domestication of the ancestor of maize — teosinte — around 5,000 B.C., and the appearance of the first distinct ceramic groups in the archaeological record, is it possible to trace the emergence of settled communities throughout the Maya area. Specialization in ceramic production and the development of distinct regional manufacturing traditions reveal not just the beginnings of sedentary life but also the rise of long-distance cultural and commercial networks.

Societies in the Maya Lowlands

During what is known as the Middle Preclassic period, roughly 1,000-450 B.C., monumental architectural complexes with large platforms appeared in the Maya Lowlands, especially in the Southern Lowlands. Initially built of earth, these platforms were gradually replaced by stone buildings. Among them are the so-called E-Groups — distinctive architectural complexes likely used for astronomical observation and commemoration. These massive pyramidal structures were crowned by three temples: a central one flanked by two smaller shrines.

At the same time, the earliest stone sculptures appear in the form of carved stelae and associated altars. Ceramic figurines with varied facial features and clothing, as well as burials accompanied by different types of offerings, all point to emerging social hierarchies that would fully crystallize in the Late Preclassic period.

This era, spanning roughly 450 B.C. to A.D. 250, marks the transition of settlements into fully urban, state-level societies with pronounced social differentiation. The earliest known examples of Maya writing, such as those from San Bartolo in Guatemala, date to this period. In the Petén region — on both the Mexican and Guatemalan sides — and the adjoining area of Belize in the Southern Lowlands, early cities such as Nakbé, Cival, Cahal Pech and El Mirador began experiencing significant growth.

The great city of El Mirador

El Mirador lies in the Guatemalan Petén, north of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, within the area known as the El Mirador Basin. Hundreds of pre‑Hispanic settlements of varying size have been documented there, including Tintal, Xulnal, Balamnal, Nakbé and others. Throughout the basin, E‑Groups and large triadic pyramidal complexes — classic architectural markers of the Preclassic period — stand out.

El Mirador was first identified in the early 20th century during expeditions led by the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Since the 1980s, it has been the focus of ongoing archaeological projects directed by Dr. Richard Hansen. Occupied since the earliest phases of the Preclassic, the site reached its peak in the Late Preclassic, when both its population and monumental architecture expanded dramatically. Some buildings, such as the great Danta pyramid, exceed 70 meters in height — roughly equivalent to a 23-story building.

A well-organized and connected metropolis

Such monumental architecture in El Mirador implies strong control over population, ritual life and cosmological symbolism, likely exercised by a ruling elite. This group would also have overseen production systems and the circulation of goods, including water and a range of commodities from basic necessities to luxury items. Excavations by Hansen’s team have revealed a network of sacbeob, or “white roads” — true pre-Hispanic highways connecting El Mirador with both nearby and distant areas.

In the first case are roads leading to what have been interpreted as suburbs or neighborhoods near the political-ceremonial core, where obsidian artifacts were produced for later redistribution. Longer sacbeob linked El Mirador to other political centers such as Tintal, about 24 kilometers to the south, and Nakbé, about 14 kilometers to the southeast. The existence of these causeways radiating from El Mirador has led Hansen to propose an early “dendritic” model of regional political organization, with El Mirador as the main hub of a territory that may have covered some 80 square kilometers.

For these reasons, El Mirador is regarded as the great metropolis of the Preclassic period, with an estimated peak population of around 100,000 inhabitants between roughly 200 B.C. and A.D. 150. Along the margins of the La Jarrilla bajo — a seasonally inundated depression that borders the city — terraces and raised fields were constructed, enabling intensive agriculture to supply the entire population. This production was likely controlled by a ruling class about which we still know relatively little.

Many triadic complexes at El Mirador preserve remains of monumental masks associated with symbols of power, such as tied knots or jaguar claws. The faces often blend human and animal features, and the few written records available do little to clarify the rich iconography seen in sculptures and stelae. Together, these factors complicate efforts to reconstruct the sociopolitical organization of this major pre-Hispanic city.

Nonetheless, these images likely represent early manifestations of political power, in which cosmogonic ideas are closely tied to the city’s ruling groups. This is why the monument known as the “Popol Vuh Frieze,” or “Panel of the Swimmers,” associated with a structure used to collect and redirect water, is so important. According to Hansen’s hypotheses, the scenes depicted there may allude to episodes in the “Popol Vuh,” the famous K’iche’ Maya manuscript compiled in the colonial era. If so, the images at El Mirador would demonstrate the deep historical roots of these ideological concepts.

Crisis in El Mirador

Around A.D. 150, El Mirador underwent a major sociopolitical crisis, probably linked in part to the intensification of building activity and exacerbated by environmental stress. Virtually all constructions — buildings, roads, monuments and so on — were coated in thick layers of white stucco and then painted in vivid colors. Because stucco erodes over time, it had to be reapplied in multiple layers. Limestone for stucco production was quarried near the site’s central sector and fired in large kilns that required enormous quantities of wood to achieve the temperatures needed to produce quicklime.

Hansen’s studies suggest that widespread deforestation and its consequences were among the key factors in El Mirador’s decline. At the same time, growing competition and political tension with other centers, such as Uaxactún and Tikal, likely contributed to the crisis.

After about A.D. 150, El Mirador’s population shrank and the construction of monumental buildings and complexes diminished drastically. Even so, the city and the basin were never completely abandoned. Archaeologists have discovered Chen Mul ceramics, characteristic of the Postclassic period (approximately A.D. 1000-1524) and the Northern Lowlands, as well as settlements with spatial patterns associated with late Kejache groups.

Despite this later occupation, the site’s decline was profound and irreversible. The once-great metropolis that had dominated the region for centuries faded into the jungle, its towering pyramids slowly consumed by vegetation. This collapse ushered in a new era that would give rise to what is known as the Classic period — a time when new centers of Maya power would emerge to fill the void left by El Mirador’s fall.

Pablo Mumary holds a doctorate in Mesoamerican studies from UNAM and currently works at the Center for Maya Studies at IIFL-UNAM as a full-time associate researcher. He specializes in the study of the lordships of the Maya Lowlands of the Classic period.