Mexican poet and academic Cesar A. Cruz once famously declared that “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable,” and nowhere is this ethos more apparent than in the works of Damien Hirst, the enfant terrible of the contemporary art world.

Until August 25, a collection of the British artist’s work is on display at the Museo Jumex in Mexico City — the first time Hirst has ever shown at the museum. A multi-floor retrospective, To Live Forever (For a While) showcases many of the themes and key works that have characterized Hirst’s polarizing career since 1986, among them a display of animals suspended in formaldehyde solution and a diamond-encrusted platinum skull — one of the most expensive works of art ever made.

The exhibition is intended to be a journey through the range of human experience, but it’s a show that will also leave you mulling over the definition of art, ethics and commercialism. Is it art? Is it not? No matter what you’ve heard about Hirst, for the intellectually curious, the exhibition is worth checking out — if only to shake up your sensibilities and formulate your take on the artist.

Hirst’s works are instantly recognizable, characterized by skulls and skeleton sculptures encased in precious metals alongside cross sections of cleanly halved creatures both real and fabricated. Stainless steel cabinets filled with jars of preserved animal remains, medical paraphernalia and butterfly mosaics serve as a canvas for his exploration of themes like death, decay and rebirth. Yet despite the visceral nature of his subject matter — preserved carcasses, animal organs, scalpels and pills — Hirst’s clean, almost clinical, approach steers his pieces away from the grotesque and towards a realm best described as artistic cataloging. In some ways, his work evokes Marcel Duchamp in its use of existing objects placed in elevated settings to provoke debate on the nature of art.

Hirst was catapulted to fame in 1991 with “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, ” a 14-foot-long tiger shark suspended in formaldehyde. The now iconic work captivated audiences worldwide and formed the centerpiece of Hirst’s “Natural History” series, encompassing various creatures such as fish, cattle, birds and sheep displayed in formaldehyde tanks. Several of these trademark specimens are on view at the Jumex museum. Hirst’s early and increasing fascination with death and preservation can be traced back through a mixed-media timeline of his career laid out on the first floor of the museum. In one photo, a young Hirst poses with an actual severed human head in a university lab.

Known as something of a jack of all trades in the public space, Hirst challenges traditional notions of an artist, transitioning between roles as an artist, curator, gallerist, museum director and entrepreneur. Some have said his approach democratizes art by bringing it to the masses in public spaces, upscale hotels and trendy eateries. Others have scoffed at what they see as his commercialization of art.

Nevertheless, Hirst’s ability to transform “controversy into currency and fame into cultural capital” highlights his legacy as a unique figure in the realm of contemporary art. Embracing a diverse array of mediums beyond painting and sculpture, Hirst’s experimentation challenges convention and leverages modern hype with ventures like the launch of his own NFT currency.

At the entrance of the Museo Jumex stands Hirst’s take on the Virgin Mother, a monumental three-story sculpture of a pregnant woman, skin peeled back to expose her organs and the developing child in her womb. Once you pass this awe-inspiring sculpture, the exhibition journey begins on the bottom floor of the museum and subsequently directs visitors to the fourth floor via elevator, where they work their way downwards through each floor of the installation.

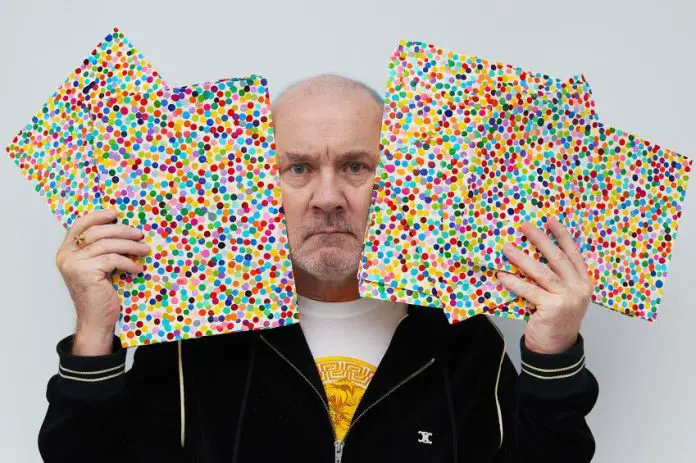

Hirst once stated that you must “kill things in order to look at them.” Whether you agree or not, the Jumex exhibition forces you to confront it firsthand. On the uppermost floor, we encounter versions of Hirst’s iconic sharks, alongside his renowned spot paintings. Here, Hirst’s fascination with taxidermy takes center stage, a theme that persists as you descend to the floor below.

While some may find these displays unsettling, there’s an undeniable fascination in witnessing the lab-like cross-sections of creatures halved — after all, when else will you get to closely observe the intact innards of a real shark, or a cow? Artnet once estimated that approximately 913,450 animals have been sacrificed for Hirst’s art. But before you cry “PETA,” know that this number includes hundreds of thousands of insects, some of them comprising his beautiful butterfly mosaic works symbolizing the resurrection of Christ, also on display at Jumex.

As you conclude your journey on the first floor, there is a decidedly airier and brighter shift in the atmosphere, in part due to the sun streaming through the floor-to-ceiling windows, but also due to Hirst’s paintings of vibrant, spring-like cherry blossoms. These works have a popular, kitschy aspect. In the center of the room, under the protective casing, is his $201 million diamond-encrusted platinum skull. Titled “For the Love of God,”, this is one of the most expensive works of art ever produced, made with 8,601 flawless diamonds, including a pear-shaped pink diamond in the forehead. According to Hirst, when he explained his plan for this piece to his mother, her reaction was, “For the love of God, what are you going to do next?”

It is fitting that Hirst’s skeletal work is being shown in Mexico, as the platinum skull was modeled on Mexica mosaic skulls in the collection of the British Museum. Given Hirst’s preoccupation with death, it is also no surprise that Mexico’s Day of the Dead has proven particularly inspiring to him. Hirst has a special connection with Mexico: he owns a house here and his work often incorporates Mexican cultural elements such as skulls, skeletons and catrinas.

Some might argue that Damien’s work lacks sophistication or complexity due to its overt exploration of somewhat obvious themes. The exhibition lays bare the most fundamental aspects of human existence in ways that are sometimes disturbing but always carefully curated. As we peer into a canvas holding a heap of black flies encased in resin, an onlooker states to his friend, “I don’t know why I’m so attracted to it. I hate it, but I love it.” And I can’t help but agree. Love it or hate it, To Live Forever (For a While) demands you confront Hirst’s art and form your own opinion.

Monica Belot is a writer, researcher, strategist and adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design in New York City, where she teaches in the Strategic Design & Management Program. Splitting her time between NYC and Mexico City, where she resides with her naughty silver labrador puppy Atlas, Monica writes about topics spanning everything from the human experience to travel and design research. Follow her varied scribbles on Medium at https://medium.com/@monicabelot.