If you’ve ever spent December 12 in Mexico City, you have seen it adorned with flowers, flags and figures of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Every year (and even during the pandemic), those devoted to La Morenita — The Dark-Skinned Virgin — travel long distances to reach the Basilica of Guadalupe, the most visited Catholic site in the world after the Vatican.

It is estimated that around 10 million people undertake this pilgrimage, often with entire communities coming together. Buses, pickup trucks and trailers transport people to the sanctuary located on Tepeyac Hill. Prayers are offered to Our Lady of Guadalupe for children to be born healthy, for work to come quickly and for the sick to be healed.

For those who grew up on the northern edge of the city, the devotion lived during these days feels absolutely magical: People fill the streets, coming from every corner of Mexico; the faithful stop traffic dead in the Tepeyac religious complex.

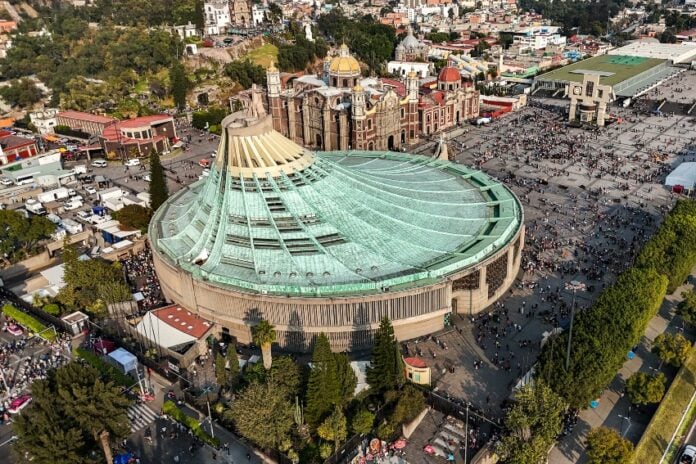

The Villa de Guadalupe complex currently comprises la Capilla del Cerrito, la Capilla del Pocito, the old basilica and the new basilica. Of the many architects who have contributed to this complex, Pedro de Arrieta and Pedro Ramírez Vázquez stand out for their work. Fittingly, their shared name, Pedro, comes from the Latin word for “stone.”

Where does the popularity of the Virgin of Guadalupe actually come from?

Coatlicue, Cihuacóatl, Tlaltecuhtli and Xochiquétzal are just a few of the faces of the goddess Tonantzin, worshipped by the Mexica (the autonym for the Aztec civilization) at Tepeyac. All these deities represent the feminine forces of fertility and creation.

Therefore, when Gonzalo de Sandoval, one of conquistador Hernán Cortés’ captains, promoted devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe — the patron saint of the city of Extremadura, Spain — at Tepeyac, the local population saw her as another manifestation of the sacred figures they had honored for centuries. Yet it would take a few more decades before her most famous image appeared. It is precisely this painted picture that is preserved in the Villa of Guadalupe.

Syncretic and enduring, the figure of Tonantzin has been reinterpreted throughout history. Today, many images draw on Mesoamerican tradition and blend it with Catholic symbolism to create a mestiza deity that reflects the origins of the people who venerate her. The reappropriation of Indigenous elements by communities today has produced new forms of syncretism that balance Catholic and Mesoamerican spirituality.

The first basílica, by the first Pedro

Now known as the Templo Expiatorio a Cristo Rey, the old basilica was begun in 1695 under the direction of architect Pedro de Arrieta. This first version of the sanctuary opened its doors in the spring of 1709, with a novena to inaugurate it.

Like much of Mexico City, the basilica was built on a lakebed, which caused significant structural damage to the building over the years. But it was the construction of the neighboring Capuchinas convent that eventually made the temple unsafe and largely inaccessible to visitors.

In the 19th century, the restoration began, turning the baroque building into a neoclassical church. From 1804 to 1836, renowned architect Manuel Tolsá oversaw the project, directed the changes, and even designed a new altarpiece with help from architect José Agustín Paz. The process took longer than expected because of an interruption from 1810 to 1822, caused by the War of Independence.

Then, in 1921, amid rising anticlerical tensions in the early 20th century, the temple was the setting of a bombing. In what some call physics and others call a miracle, the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe suffered no damage in the attack.

According to physicist Adolfo Orozco, who conducted a study on the case, the attack exploded with such violence that all the windows nearby were broken, but the canvas’ protective glass remained intact. The faithful say a bronze crucifix placed in front of the Virgin protected the image from harm.

The ephemeral basilica

During the 50th anniversary of the Virgin’s coronation, in 1970, Fray Gabriel Chávez de la Mora realized that there was not enough space for visitors. People had to wait long hours to see the Virgin, standing in the sun, so he came up with an idea: an ephemeral basilica.

Though unconventional at the time, Chávez de la Mora decided to place an enormous tent in the church’s atrium. This structure would allow more people to gather for Mass during this special day.

He quickly realized the expansion should not be temporary, so he called in architects Pedro Ramírez Vázquez and José Luis Benlliure.

The second basílica, by the second Pedro

In the course of his life, Vázquez built two temples: one guards the country’s archaeological treasures (the National Anthropology Museum), the other guards its faith.

In designing the second basilica for Chávez de la Mora, the architect wanted to reference the earlier ephemeral basilica the friar had created, as a reference to the massive crowds of Our Lady of Guadalupe and the need to accommodate them.

Along accessibility lines, Ramírez Vázquez designed the sanctuary’s interior without columns so that the Virgin could be seen from every corner. To him, nothing should stand between the worshippers and their object of faith.

On the outside, the architect tried to depict the crown at the top and a cross with extended arms, ready to receive every pilgrim. However, the modern image of the new basilica sparked mixed reactions: Visitors were accustomed to the traditional architecture of the first basilica, with its small spaces and neoclassical elements.

As decades went by, however, the new structure was accepted, though older people still remember the first temple dearly.

If you are ever in Mexico City in mid-December, head to the Tepeyac to witness a spiritual commitment to Our Lady of Guadalupe older than both basilicas.

Lydia Leija is a linguist, journalist, and visual storyteller. She has directed three feature films, and her audiovisual work has been featured in national and international media. She’s been part of National Geographic, Muy Interesante, and Cosmopolitan.