Yes, it happened — again. Earthquakes are one of those annoying peculiarities of the our beloved Mexico City. However! These natural (yet terrifying) phenomena bring back ancient devotions to the deities that made the earth roar. For the Indigenous people of the Valley of Mexico, that means the return of the terrifying Tepeyóllotl.

Like the rest of the region, the capital is subject to the seismic activity of our majestic volcanoes, Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl. Although at this time of year the pair gives us magnificent views of their snow-covered faces , it is also true that they are some of the most active volcanoes in the world — hence, we get pretty strong earthquakes! If the editors will allow me a superstitious note, it’s best to offer a prayer to the One Who Moves the Earth when we are surprised by tremors like yesterday’s! Here’s everything you need to know.

The mountain-heart guardian of the Valley of Mexico

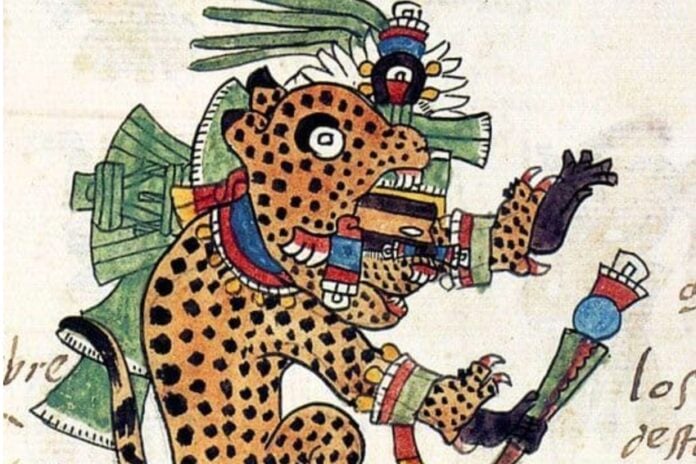

Tepeyóllotl is the Mexica god of earthquakes and seismic activity. His name translates from ancient Náhuatl as ‘Heart of the Mountain’, and was commonly represented as a jaguar who inhabited mountains. It was said that his roar caused deadly earthquakes, a common occurrence even in pre-Columbian times in present-day Mexico. However, he was also associated with echoes and the night, as this feline is a silent night hunter.

As was common in Mexica mythology, the gods had ‘avatars’ — or manifestations — who served specific purposes. For example, Quetzalcóatl was frequently represented as Ehécatl, the venerable lord of the wind.

Ancient Mexica priests honored Tepeyóllotl as a manifestation of the powerful Tezcatlipoca, one of the most venerated gods in the Mexica Empire. In their world vision, “his presence was omnipresent, embodying the duality of life and death”, as described by UNAM’s Institute of Historical Research.

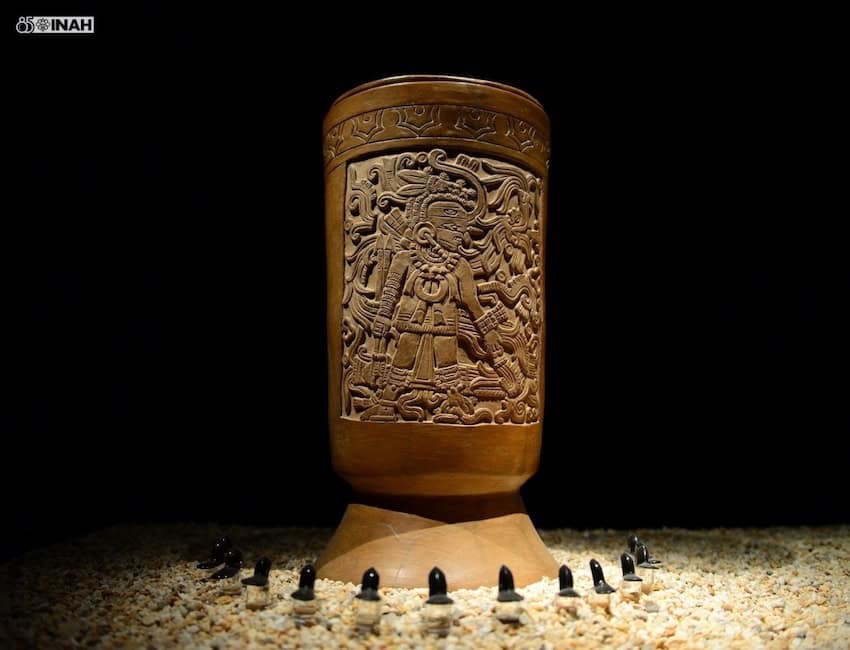

Tepeyóllotl mirrors Tezcatlipoca’s dark and nocturnal nature, often depicted as “the Sun descending to the realm of the deceased.” As much as he was feared as a liminal deity, who bestowed life and death upon the inhabitants of México-Tenochtitlan, he was also revered as the “empty space” in the Cosmos. No wonder several offerings to him have been found in the Templo Mayor site.

Tepeyóllotl, the great Lord of Earthquakes

Tepeyóllotl inherited the destructive power of Tezcatlipoca. As unpredictable as earthquakes are, it was known that Tepeyóllotl was capricious and erratic. Just as he inherited Tezcatlipoca’s destructive power, like all good cats, he also had a fickle character, which kept the inhabitants of the imperial capital on their toes. Nobody knew when he might attack: whether in the middle of the night, as jaguars usually do, or in broad daylight. So yes, he was a moody one, wasn’t he?

Considering the above, there is evidence that the ancient Mexicas built their civil and residential buildings taking into account the intense seismic activity inherent to their territory, according to the UNAM’s Institute of Engineering. To prevent landslides and collapses, they modified the course of some of their rivers and secured the flourishing city with quite effective urban engineering — so much so that it allowed them to live for centuries on a lake.

Although he appears to have been a widely venerated deity in Mexico-Tenochtitlan, as anthropologist Luz María Guerrero wrote for Estudios de la Cultura Náhuatl magazine, few records survive of the jaguar god of echoes and earthquakes. The oldest representations date from the 16th century — long after the fall of the great imperial capital.

From the few accounts we have, we know that Tepeyóllotl was depicted with stars for eyes, his characteristic jaguar attire and bandages covering his face. Sometimes, he is shown with a beard, a necklace of rattles and an obsidian mirror on his temple, similar to Tezcatlipoca. Iconographically, his fierce and destructive nature is suggested by a series of knives hanging from his body.

He was repeatedly described like this in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis and the Vatican-Latin Codex, and for his thunderous roar, “that echoed in the mountains” and was “a sign of bad luck that preceded death, misery and disease.” Given his humongous destructive power, no wonder we get terrifying earthquakes in the Basin of Mexico!

Andrea Fischer contributes to the features desk at Mexico News Daily. She has edited and written for National Geographic en Español and Muy Interesante México, and continues to be an advocate for anything that screams science. Or yoga. Or both.