Gentrification is the buzzword going around Mexico City right now, with recent protests encouraging a policy response from Mayor Clara Brugada, but it is showing no signs of slowing. When we talk about gentrification in Mexico City, many think of digital nomads in hipster cafes in Roma, Condesa and Juárez, but the phenomenon is much more complicated. As these three areas get more popular, the gentrification bubble expands, pushing Mexicans out from the traditionally middle-class neighborhoods on the borders of these three in-demand areas, to make room for the demand for new expensive developments, not only by foreigners but also by wealthier Mexican residents.

As the urban center of Mexico City has expanded, driving people beyond Roma and Condesa, Tacubaya has become more attractive to investors who are looking for the next new space to build for the affluent.

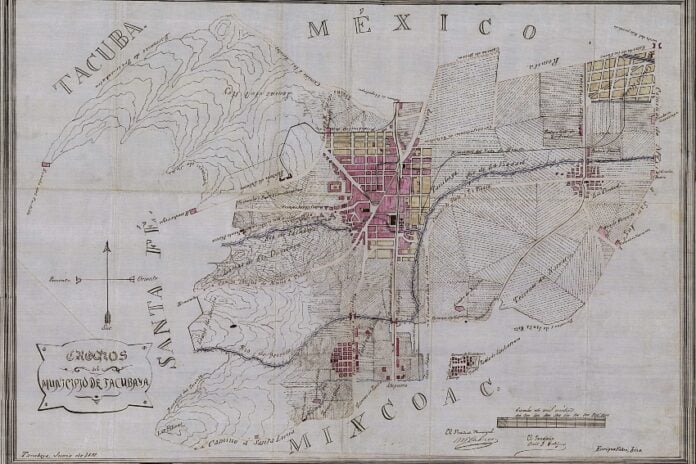

A brief history of Tacubaya

The ancient city of Tacubaya was known for its strategic access to fresh water. It became known as Atlalcuihaya, meaning “where water is gathered” in the Náhuatl language, before becoming the Spanish Tacubaya. It was a suburban municipality of the city in the 19th century, and landlords began to build several churches, water mills and haciendas, including two that still exist — the museum of Casa de la Bola and the government office of Casa Amarilla, with Parque Lira connecting the two.

However, in 1928, the Mexican government reworked Mexico City into one central department that incorporated the municipalities around Mexico City, including Tacubaya. Urban development quickly transformed the area, with large haciendas giving way to mixed-use complexes and multifamily buildings.

Transformation from utopia to urban transport hub

Surrounded by parks and plazas, early developers saw the neighborhood as ideal for walking and socializing. Sprawling avenues quickly appeared, however, as tram lines disappeared to make way for cars. In the 1970s and 1980s, the government ran three new metro lines through Tacubaya, while the Viaducto and Revolución roads connected the area to the north, south, east and west of the city.

By the late 20th and early 21st century, however, underinvestment in the once-booming area led it to fall from grace, as Tacubaya became more insecure, with crime rates rising. What had happened?

The Lost City and public investment during COVID-19

One answer is to be found in an irregular settlement, known as the Ciudad Perdida (Lost City), that emerged in the 20th century, housing impoverished families in makeshift structures amidst abandoned mines. This drove Tacubaya’s image of urban decline.

It wasn’t until the pandemic, with government investment in the development of the Ciudad Bienestar project, in place of the Lost City, that things began to change in Tacubaya. The 110-million-peso (US $6 million), 185-apartment complex offered families free homes, and those apartments are thought to have a value of around 759,000 pesos each, or up to 3 million pesos, if land value is taken into account.

This set the stage for Tacubaya’s renaissance.

The new Tacubaya

Over the last decade, Tacubaya has undergone a significant shift. Where there was once a miscelánea (corner store) stands a natural wine store, and just behind that, a popular nightclub. Moving closer to Avenida Revolución, you will see a white-washed Tacubaya, the “safe” area, which is swept daily and where there are more streetlights. It is the area where “creatives” have flocked over the last century to reside in historic but affordable buildings, such as Edificio Ermita and Edificio Isabel. It is where I, myself, have lived for the last 11 years. It reflects the first major wave of gentrification, when rent control was scrapped in some buildings and long-term residents were forced out.

However, upon crossing Jalisco road, the true Tacubaya comes into sight. Closer to the metro and bus stations, you see a neighborhood still filled with market stalls, arcades and fairgrounds, one where there are fewer new developments — so far.

As high-rises sneak closer to the border between the two Tacubayas, it seems clear that developers are seeking to erase this Tacubaya, one street at a time, as the potential real estate profits grow ever more attractive.

The seeds of Tacubaya’s gentrification

It should be no surprise that this is happening: Mexico City’s public policy since the 1990s has focused on raising the density of the central boroughs, and developers have been encouraged to build in them. This has gone hand in hand with public investment in communal spaces and transportation in certain areas.

Neighborhoods chosen for improvement, such as Tacubaya, have become more attractive places to live. The perceived beginnings of a transformation in the area spurred developers to construct several large-scale buildings on more affordable land, as they speculated correctly that the area’s housing market would rise in value.

But all this has also meant that newer residents, with greater purchasing power, have driven an increase in the cost of living, and that the area’s current longtime residents are being forced out.

A new law ramps up development

In 2021, a new law was established that included an agreement between the city and developers on the administrative procedures for real estate projects within the “Cooperative Action System” (SAC) of Tacubaya. The government aimed to “coordinate the actions of the public, social and private sectors for projects and works to revitalize and requalify the urban area.”

This agreement spurred a boom in development in the area during the pandemic — just as working families and digital nomads from other countries flocked in droves to Mexico City, thanks to work-from-home mandates that freed them to live anywhere. Thanks to the law, developers could now build more stories in exchange for a contribution to the city government for public works — which reportedly never came to fruition. As developers rushing to meet new demand pushed into Tacubaya, locals facing rising prices and mounting pressure from these developers sought a way to discourage further gentrification. By 2024, the San Miguel Chapultepec and Escandón I neighborhoods were removed from the Tacubaya SAC agreement at residents’ request.

Could advertising practices erase Tacubaya’s identity?

This victory, however, has not stopped development in Tacubaya. And as developers look for affluent clients to occupy their projects, they have increasingly resorted to questionable advertisement practices that seek to blur the boundaries between Tacubaya and its more affluent next-door neighbors in the minds of clients.

A good example is a development that arose on Antonio Maceo Street, where the emblematic 1950s Hipódromo Cinema was demolished. A new 16-story building, consisting of apartments, a HS HOTSSON hotel, a gym and several other businesses, took its place. But Homie, the company in charge of its marketing, decided to name the development Condesa Sur (South Condesa), clearly hoping to associate the development with the more affluent Condesa neighborhood nearby.

According to the newspaper NMás, “The construction of new residential developments is accompanied by a strategy of erasing the names of neighborhoods that carry a history of danger and precariousness.”

Removing traditional names

Journalist Mariana Aguirre wrote in the same article, “The Guerrero neighborhood, next to the rough neighborhood of Tepito, is now ‘Reforma Norte’ in advertisements. The Doctores neighborhood is now ‘Roma Oriente,’” these manufactured names seeking association with the better-regarded adjacent neighborhoods of Reforma and Roma.

Studio apartments in the new Condesa Sur development reportedly cost 14,000 pesos ($776) a month, while two-bedroom apartments with amenities go for 20,500 pesos ($1,410). For context, the minimum daily salary in Mexico City was 278.80 pesos in 2025, meaning it would take a minimum wage worker more than 50 days of labor to earn the money needed to pay for a month’s rent on a studio apartment there.

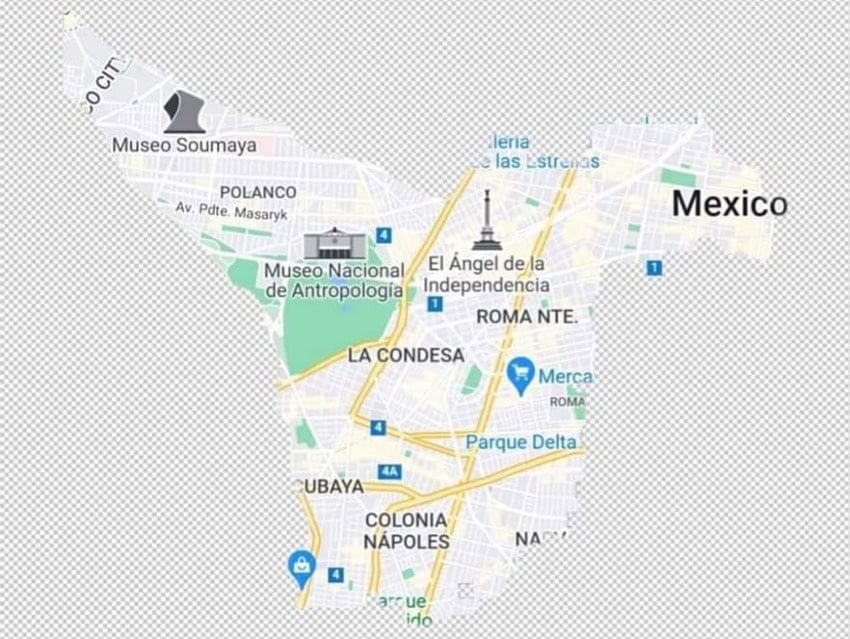

Other new developments in Tacubaya, located on the borders with the more affluent Escandón and Condesa neighborhoods, also seem to be willing to blur the lines between the different neighborhoods, expanding the bubble where it is acceptable to live, as shown by the circle on the map below, one that many foreigners share when looking for an apartment to rent.

The transformation of an icon

Shortly after the development of the Condesa Sur project, developers began work on transforming Tacubaya’s Ermita Building. Known as Mexico’s answer to New York City’s historic Flatiron Building, the Ermita was a Mexico City icon during the first half of the 20th century, recognizable by the larger-than-life ads for brands such as Coca-Cola displayed on its facade.

During the pandemic, the building’s owner — the Mier y Pesado Foundation, which has owned the building since its construction in the early 1930s — evicted residents from the Ermita, some of whom had lived in the building their whole lives. The foundation planned to carry out a complete renovation of the building to offer new tenants a space on the border of the Condesa neighborhood — at a much higher price than usually found in Tacubaya.

If you’d like a taste of what Ermita living was all about, in 1983, Alfonso Cuaron, the well-known director of the film “Roma,” filmed his short, “Quartet for the End of Time,” in the building. And in 2019, Daniela Uribe produced a documentary on the lives of eight of the building’s residents, entitled “Ermitaños” (which also means “hermits”), giving an insight into their day-to-day lives.

Evicting residents to make way for wealthier ones

The renovation of the Ermita, with its accompanying eviction notices, felt like the beginning of a broader phenomenon. Instead of simply building new high-rises on empty plots of land, developers were now transforming older historic spaces to make way for wealthier residents, evicting current residents.

Meanwhile, seeing the success of the neighboring Condesa Sur building, Mier y Pesado contracted Homie to do the marketing for the new and improved Ermita, with rental prices starting at 14,900 pesos ($820) — nearly 1,000 pesos more a month than at Condesa Sur — and rising to 31,500 pesos ($1,735) for a two-bedroom penthouse. This is in comparison to rental prices starting at around 4,500 pesos ($250) in 2020, marking more than a 300% increase.

Just across the road from Ermita, and actually in Condesa, Espacio Condesa is now under development, with 31 floors, including offices, apartments, a gym and a shopping mall. Once complete, it will likely increase traffic in the area and drive up housing demand just over the border in Tacubaya.

Meanwhile, the development push continues: A major new apartment complex next to Alameda de Tacubaya Square, Living Enjoy Escandón, is also being advertised. Once again, developers are shying away from the name Tacubaya and opting for the more attractive “Escandón” — since the Escandón neighborhood is located just across the street from the project and shares a border with Condesa as well as with Tacubaya.

The development’s Instagram account shows renderings of an 18-floor building and says that apartments will be available for presale starting at 3.3 million pesos ($182,950) by summer 2027.

The most expensive places to live

These new developments in Tacubaya have driven rental prices throughout the neighborhood sky high. According to data from the most recent real estate market report from the property site Propiedades.com, rental prices in Tacubaya have risen to an average 352.52 pesos (US $19) per square meter, placing Tacubaya at No. 14 among the most expensive neighborhoods in the city — only slightly behind the prestigious Roma, where prices average 362.69 pesos ($20) a month per square meter.

By contrast, in 2023, the rental portal listed Tacubaya’s average property prices at 197 pesos ($11) per square meter a month, marking an increase of over 78% in just two years.

With greater investment in the zone, crime rates have also decreased. According to the Hoyo de Crimen website, which uses Mexico City government data, the rate of violent robberies of pedestrians in the area has fallen over the last six years, from 473.4 recorded cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2019 to 290.1 in March 2020 and 183.2 in March 2025. This has helped to shift the perception of safety in the area, as visitors venture further out of their bubble and into Tacubaya.

Gentrification by design

It would be naïve to think that gentrification in Mexico City is only taking place in Tacubaya, as a century of urban development history shows. But this latest wave of high-rise construction, the destruction of iconic buildings and the rebranding of neighborhood names, which undeniably have more of an impact and threaten to erase Tacubaya’s rich history, are creating a more visually and demographically homogenized space, repeating the trend that has been seen in several other parts of the city.

So, when you suddenly hear about “hot new neighborhoods” in Mexico City you’d previously never heard of, know that this is not by chance; rather, it is by design.

Felicity Bradstock is a writer for Mexico News Daily.