November 20, 1935: Nazi-aligned paramilitaries charge on horseback. Communists under the red flag zoom towards the enemy in dozens of cars. A 16th-century plaza witnesses it all. Where is this? The actors and year suggest Poland, Germany or France. But this is four years before World War II breaks out in Europe, and far from the battlefields of Old World Europe. This scene is happening in the Zócalo, the heart of Mexico City — on Revolution Day, no less. At the end of it all, three people will be dead and dozens injured.

How did this dress rehearsal for the Second World War come to happen in Mexico, of all places? What did it mean? Read on to find out.

The Cárdenas years

There’s no making sense of the Battle of the Zócalo without understanding the national politics of 1930s Mexico. Though the progressive Constitution of 1917 had been in place for over a decade, many historians will tell you it wasn’t until the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas that the promises of the Mexican Revolution finally began to be fulfilled.

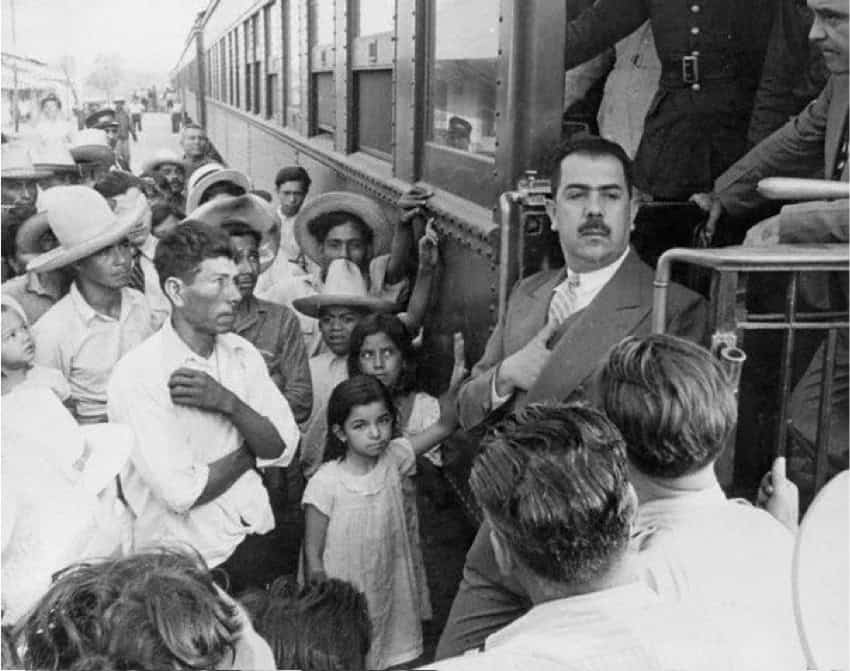

An economic nationalist and former officer in the Constitutionalist faction during the Revolution, Cárdenas ran under the slogan of “Mexico for the Mexicans.” The first year of his government centered on a power struggle with former president Plutarco Elías Calles, who had all but controlled the previous three presidents in the period known as the Maximato. To cement his own position, Cárdenas looked to build alliances with broad sectors of society and turned to the country’s peasants and workers.

Land reform, the central demand of the Revolution, took off under Cárdenas’ government, with the state redistributing more land to peasants than all previous post-revolutionary governments put together. The first years of Michoacán native’s rule also saw the president ally with industrial labor, pushing for the fragmented workers’ movement to reorganize under a new umbrella organization, an effort that led to the formation of the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM), to this day Mexico’s largest labor union confederation. In the following years, labor militancy would help Cárdenas to expropriate and nationalize Mexico’s oil and railways.

Communists and fascists in Mexico

Enter the Mexican Communist Party (PCM). Founded in 1919, the PCM had been forced underground by the government in 1930, with many leaders deported or jailed in the infamous Islas Marías penal colony. It continued working underground into the 1930s, and despite its reduced membership, was an important player in peasant organizing in many states across the country. When Cárdenas took office, restrictions on the PCM were relaxed, and the party returned to public activity.

None of this peasant and labor organizing was welcomed by Mexico’s middle and business classes, who were, moreover, horrified by the government’s easing up on the PCM. They organized too, and where the Mexican communists looked to Moscow for inspiration, the middle classes looked to Berlin and Rome. Where the Nazis had the brownshirts and the Italian fascists had the blackshirts, those who followed their example in Mexico founded the Gold Shirts, also known as Revolutionary Mexicanist Action, in the year that Cárdenas took office.

Supported by the German embassy and led by a former Villista soldier named Nicolás Rodríguez Carrasco, the Gold Shirts opposed Cárdenas’ government, violently broke up labor strikes and preached the expulsion of Chinese and Jews from the country. They were joined in their organizing by organizations like the Pro-Race Committee, the Employers’ Confederation of the Mexican Republic and the Anti-Chinese League and received the financial backing of industrialists of the stature of Eugenio Garza Sada, owner of Cuauhtémoc Brewery and one of Mexico’s richest men.

The communists denounced the anti-foreigner rhetoric of these groups as a trick to take pressure off of Mexican capitalists, while the fascists, attacking small Jewish and Chinese merchants, pointed to the PCM as a manifestation of the Jewish-Bolshevik plot to destroy Mexico. When the PCM tried organizing workers, the Gold Shirts would attack their picket lines and break up their strikes.

Almost every month of 1935 saw violent incidents between fascists and the labor movement. In March, the Gold Shirts took over the PCM’s Mexico City offices, wounding several members and burning party literature, provoking demonstrations in solidarity with the communists around the country. In August, workers and Gold Shirts traded gunshots in Tizapán, Mexico City, and the communists held increasingly massive anti-Nazi rallies around the capital as autumn rolled around. The stage was set for a bloodier confrontation. It came on Revolution Day.

The Battle of the Zócalo

Mexican Revolution Day celebrates Francisco I. Madero’s Nov. 20, 1910, call to the Mexican people to overthrow the dictator Porfirio Díaz. Today, it is celebrated with a military parade in the nation’s capital, a tradition which in 1935 was only a few years old— it would not be until a year later that Revolution Day was officially declared a national holiday. That day, in fact, was the first time that the holiday would ever be celebrated by a sitting president, and the plan was for Cárdenas to watch the civic-military parade from the central balcony of the National Palace.

The best description of what happened in the Zócalo on that day comes from the pen of journalist Mario Gill. Gold Shirt leader Nicolás rode at the front of a “militarily organized column, with uniformed infantry and a cavalry detachment, marching in correct formation.” Leading the communists was no less than the painter David Álfaro Siqueiros, already famous then and today remembered as one of the “Big Three” of Mexico’s world-famous muralist movement. It was PCM member and railroad worker Valentín Campa, however, who was in charge of the strike against the Gold Shirts. The fascists were determined to march before the eyes of President Cárdenas, and the communists were determined to stop them.

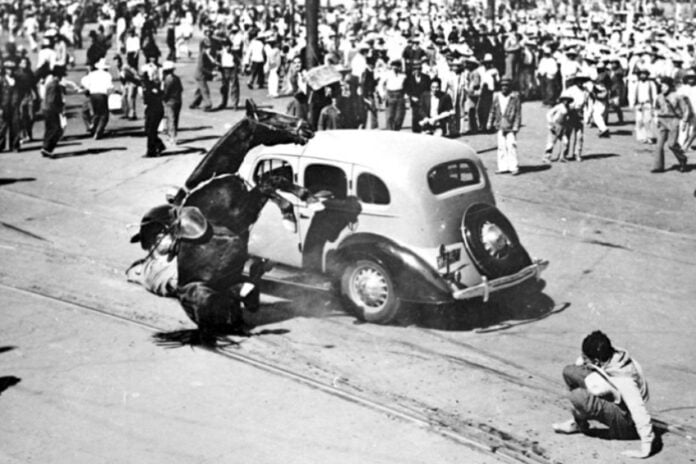

As the Gold Shirt column approached the National Palace, a group of young communists emerged from the crowd and threw firecrackers down at their horses’ feet, causing the animals to panic. At the same time, other militants took the Gold Shirts by surprise with sticks and stones. The shocked fascists defended themselves with whips and riding crops, but the bulk of the PCM’s attack was still to come. As the two sides fought, writes Mario Gill, “a small, secretly organized fleet of cars manned by drivers of the Taxi Drivers Union, PCM members, launched themselves without warning against the cavalry in a rapid flanking move.” Dozens of Gold Shirts and their horses, rammed directly by the cars, rolled in the dust. In an instant, the Gold Shirt column was dispersed, with the riders who had managed to stay mounted taking off down the streets of the Historic Center.

Nicolás Rodríguez, knocked off his horse in the car strike, was spotted fleeing the Zócalo by a young communist named Rafael Galván, who pursued and stabbed him on the corner of Calle República de Argentina and República de Guatemala. When the dust settled, around three dozen people were wounded and three were dead, including the young communists Carlos Salinas Vela and J. Trinidad García.

The battle after the battle

The next months were pivotal for both sides. The Communist Party’s prestige may never have been higher, evinced by the fact that 15,000 workers and students attended the funeral of Salinas and Trinidad. The government came under increased pressure from the labor movement and civil society to ban Revolutionary Mexicanist Action, which it did in February 1936. Nicolás Rodríguez, left for dead, survived his injuries and headed north to Monterrey, where he was apparently soon involved in more violence.

The struggle between Mexico’s communists and fascists didn’t end there, however. Not to be deterred, the former Gold Shirts reorganized within groups like the Nationalist Union, Mexican Nationalist Vanguard and, most famously, the National Sinarquist Union. Despite Mexico entering World War II on the Allied side under President Manuel Ávila Camacho, its anti-Jewish agitation in the ‘30s had already borne fruit in the shape of Mexico’s secret 1934 ban on Jewish immigration. The powerful business interests that had backed the Gold Shirts carried on their struggle in politics, with backer Eugenio Garza Sada supporting right-wing presidential candidate Juan Andreu Almazán in the 1940 elections. Those elections, overseen by Lázaro Cárdenas, are widely believed to set the precedent for the electoral frauds that would characterize Mexico for much of the rest of the century.

The PCM’s alliance with the ruling party was short-lived. Cárdenas’ party, the PNR, was abandoning its radicalism. It wanted to be the only game in town, and there was no way it could tolerate a movement working for another revolution in Mexico. Relations between the PNR and PCM declined in the last year of Cárdenas’ government, and the day before the president’s term ended, the government raided the communists’ headquarters and arrested dozens of party members. The government of Manuel Ávila Camacho continued to sideline the PCM, and by the 1950s, anticommunist repression was back on.

What did the Battle of the Zócalo mean?

Seen from nearly a century’s distance, the Battle of the Zócalo stands less as a dress rehearsal for Europe’s coming catastrophe than as a vivid expression of Mexico’s own unresolved social battles. Although both the PCM and Gold Shirts understood themselves as part of worldwide movements, their clash that November afternoon was born not of foreign scripts but of the home-grown tensions — between workers and industrialists, peasants and landowners, revolutionaries and counterrevolutionaries — still shaping the young post-revolutionary state.

In that sense, the Battle of the Zócalo didn’t prefigure Mexico’s future so much as it illuminated the fault lines of its present. And though the Gold Shirts were scattered and the PCM was soon pushed back underground, the forces they represented remained embedded in Mexican political life. Long after the dust of November 20, 1935, had settled, the struggle over what the Revolution meant, and who it was for, continued to shape the country’s path through the 20th century and beyond.

Diego Levin is a historian and researcher.