In the beginning of 1942, the Mexican government was relatively unconcerned about World War II. Europe was far away. It was not Mexico’s war.

But when the nation did finally join the war, it turned to an unlikely source for their front line of defense: the Legion of Mexican Guerrillas — a network of charros (think Mexican cowboys) throughout the country, who were trained to fight the Nazis if they invaded Mexico.

The threat was very real: Hitler was interested in Mexico’s oil reserves.

According to German historian Friederich Katz, the Nazi party had penetrated the political and economic life of Mexico through the backing of big German companies. Historians and writers have documented the influence the Third Reich had on the German community here. In the Mexican capital, there were episodes of violence against Jews, Chinese, communists, and trade unionists. Swastika flags waved at the doors of German businesses.

Then, in May of 1942, the unthinkable happened: a German submarine torpedoed and sank two Mexican oil tankers — the Potrero del Llano and the Faja de Oro – in the Gulf of Mexico.

Mexican President Manuel Ávila Camacho gave up neutrality and declared war on the Axis powers — Germany, Italy and Japan — on May 28, 1942.

But Mexico’s army and air force were small and had not been professionally trained. Sophisticated equipment was nonexistent — they had no tanks, no combat planes and no submarines. Camacho would have to rely on the patriotism and ingenuity of the Mexican people. At the end of his speech declaring war, the president appealed to the nation: “Mexico expects each of its children to fulfill his duty.”

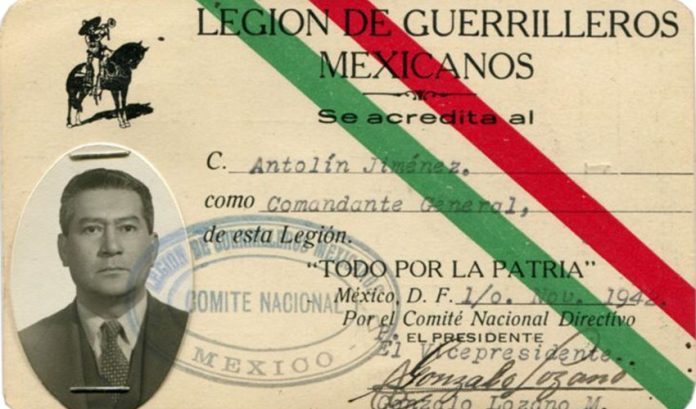

Antolín Jiménez Gamas — a patriotic ex–combatant of the Mexican Revolution and President of the National Association of Charros — responded to the president’s call to action. He proposed that the charros be organized as a militia to fight the Nazis if they invaded the country.

Charrería — the horsemanship tradition still practiced by charros today — dates back to the Spanish conquest, when they were enlisted to protect the haciendas of wealthy landowners. These charros were skilled horsemen and knew how to use machetes and pistols.

Camacho agreed to his proposal, and with his backing, Jiménez formed the Legion of Mexican Guerrillas two months later.

He then enlisted the help of his friend, former President Lazáro Cárdenas (1934-1940) — a general in the Mexican Revolution and Secretary of National Defense under Camacho — and other ex-combatants of the Revolution to train the charros in military strategy and guerrilla tactics. The charros trained every Sunday for the next year in preparation for a Nazi invasion.

With the declaration of war, ideologies were stirred up in the capital. Nazi sympathizers came out of anonymity to demonstrate their loyalty to Germany. Even intellectuals like José Vasconcelos — a nationalist — leaned towards Nazi Germany.

Loyalties in Mexico City’s German community were divided. Many prominent German emigrants opposed the war and became part of the Free Germany movement.

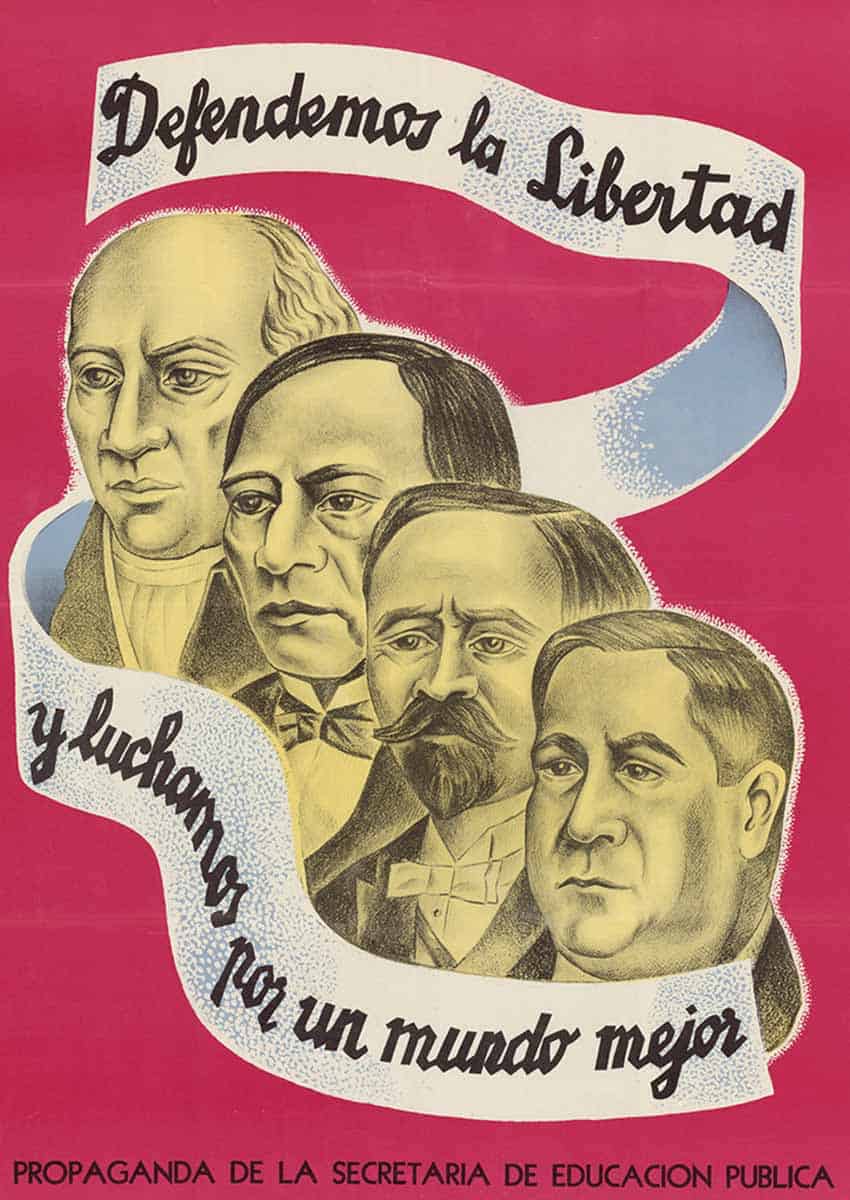

The charros — proud Mexican men in traditional costume sitting astride their horses — became a patriotic symbol to the nation. Their motto was “Everything for the Homeland.” To their supporters, they symbolized the “good guys”, opposing the Nazis, the emblematic figure of the “bad guys.”

Newspapers across Mexico proudly touted the fact that Jiménez had organized 150,000 charros stationed at 250 locations throughout the nation to fight the Nazis.

Although it may seem silly now — even absurd — to envision charros with machetes and pistols standing up to the Nazis’ heavily armored tanks and combat planes, the charros took their role in the war very seriously.

In Mexican history there are often contrasts — sometimes conflicts — between tradition and modernity.

Camacho, confident that the charros would protect the homeland, looked for other ways to assist the allies in the war effort. He created the Mexican Expeditionary Air Force (FAEM).

Ever since the Mexican-American war the United States and Mexico had an uneasy relationship. Camacho would usher in a new era of cooperation by fighting the Nazis side-by-side with the Americans.

The United States needed raw materials for the production of tanks and planes. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and President Camacho forged an alliance. Mexico would provide the Americans with the raw materials they needed, and in return the United States would provide Mexico with planes and pilot training.

The 300 members of the 201 Squadron of the Expeditionary Air Force — known as the Aztec Eagles — were sent to the United States for training. After months of intense training exercises — in June of 1943 — the Aztec Eagles were sent to East Asia to fight the Japanese in the Philippines. They fought side-by-side with the American pilots who were impressed with their courage and fierceness.

The war ended September 2, 1945 when Japan surrendered–the Aztec Eagles returned home to a hero’s welcome. The Nazis never invaded Mexico, so the Legion of Mexican Guerrillas – although considered heroes – never got to fight and disbanded.

The story of Antolín Jiménez and the Legion of Mexican Guerrillas was not widely known until 2014, when Jiménez’s grandson Fernando Llanos — a documentary filmmaker – found his grandfather’s memorabilia and press clippings from World War II.

It was a family history his family had never revealed to him . In the process of researching his grandfather, Llanos discovered that Jiménez had also been a 33-degree Freemason, one of the founders of PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), a publisher, and had been elected to the Chamber of Deputies three times.

He knew he had to tell Jiménez’s story.

After four years of research, Llanos produced and released the documentary “Matria” in 2014 — a tribute to his grandfather and the charros who were prepared to fight a Nazi invasion. It won the award for best documentary at the 2014 Morelia International Film Festival.

Llanos said at the time that if he had to sum up his grandfather’s life, it would be with the motto Todo por la Patria.

The National Association of Charros still exists today, and the equestrian tradition of charrería is practiced throughout Mexico. In 2016, UNESCO named charrería to its list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, citing it as an important element of the identity and cultural heritage of the communities that hold this tradition and the important social values—such as respect and equality – one it continues to transmit to new generations.

Trailer, Matria

The trailer for the documentary “Matria,” written and directed by Jimenez’s grandson, Fernando Llanos. It was released in 2014 and won the top documentary prize at that year’s Morelia International Film Festival.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.