The robbery at Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology remains one of the most astonishing events in art history. This is what happened.

It was Christmas Eve in 1985, and nearly everyone in Mexico City was celebrating with family and loved ones — almost everyone. On the outskirts of the capital, two young veterinary students had a very different plan in mind: robbing the National Museum of Anthropology.

Christmas shadows

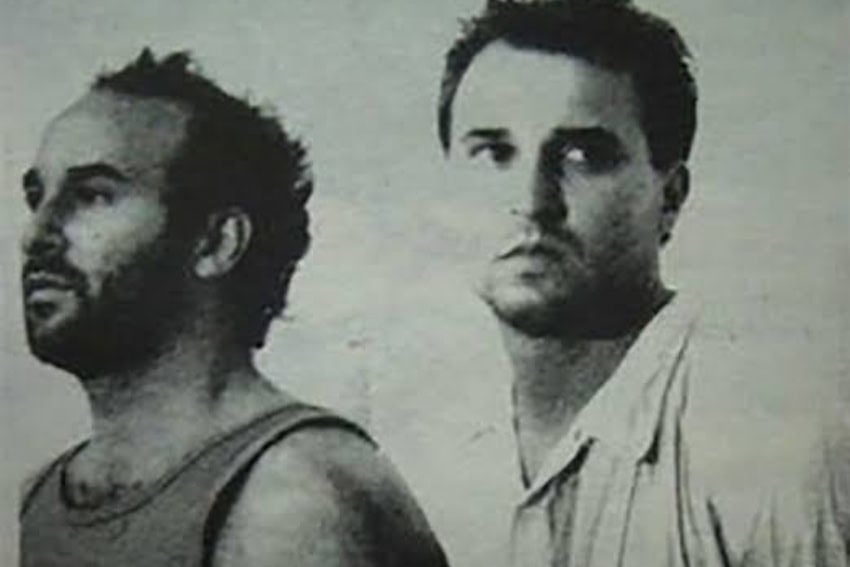

For six months, the alleged perpetrators of the heist, Carlos Perches and Ramón Sardina, planned exactly how they would enter the museum. The two inspected every possible entrance and exit. They conducted a meticulous review of the museum’s most valuable and beloved artifacts and visited the museum at least 50 times to ensure that everything would be under control on the day of the robbery. Finally, during the December festivities, they decided to make their move.

According to the investigation afterward, they climbed over one of the museum’s walls and entered through an air duct. Despite the presence of nine guards on site, they managed to slip past security and reach the exhibition halls. At the time, the museum had no alarm system, and many artifacts were likely neither individually cataloged nor insured.

The Crown Jewel

It is estimated that Carlos and Ramón entered the building between 1:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m., a perfect three-hour window to remove around 140 pieces from the museum’s galleries. The precision of the selections made it clear they had studied not only every room, but also the artifacts themselves and their histories.

Among the objects taken were the famous Mask of Pakal, the Bat God Mask and the Obsidian Monkey Vessel, along with smaller pieces of gold jewelry and jade ornaments. That same morning — while children across the country were opening Christmas gifts —journalist Jacobo Zabludovsky announced the dramatic news that a gang of thieves had looted one of Mexico’s most important historical institutions.

Facing the Consequences

The director of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) at the time, Enrique Florescano, stated that the robbery was not discovered until the next day, when the night guards switched shifts with the morning staff. He also maintained that the heist was not an isolated event but part of a wave of art crimes that had taken place in different countries throughout the decade.

The Mexican government partnered with the media to encourage citizens to report any information that might help locate the missing pieces. Shortly afterward, INTERPOL joined the search, and Mexico reinforced its borders to prevent the perpetrators from leaving the country.

No apparent motive

Nearly four decades later, the motive behind the theft remains a mystery. From a trafficking standpoint, the artifacts were so valuable that they would have been impossible to sell.

Their historical importance makes them priceless, and their uniqueness makes them perfectly traceable. Any attempt to traffic them would have immediately revealed the culprits. Likewise, it is improbable that any buyers existed; no collector, no matter how bold, would risk possessing such recognizable artifacts.

Aftermath of the museum heist

The National Museum of Anthropology did not close its doors and continued to receive visitors. Surprisingly, attendance actually surged. Thousands of people of all ages came to marvel at the empty display cases.

“After the robbery, the museum was visited much more than before. People came to see the empty cases, which relates to that saying: ‘You don’t know what you have until you lose it,’” actor Gael García Bernal remarked about a film (“Museo,” 2018) inspired by the historic event.

In the end, the artifacts did resurface — but in the most unexpected way. Four years after the robbery, Carlos Perches’ mother found the pieces while cleaning her son’s closet. Shocked and terrified, she went straight to the museum carrying suitcases filled with priceless artifacts, bringing the dramatic chapter to a close.

Lydia Leija is a linguist, journalist, and visual storyteller. She has directed three feature films, and her audiovisual work has been featured in national and international media. She’s been part of National Geographic, Muy Interesante, and Cosmopolitan.