When University of California at Riverside history professor Jennifer Scheper Hughes researched the epidemics that devastated Mexico in the decades following the Spanish conquest, she found an overwhelming amount of information on a five-year outbreak of an unknown deadly illness that began in 1576 and that she believes led to lasting change for Christianity and Catholicism in Mexico.

She makes this case in her new book, The Church of the Dead: The Epidemic of 1576 and the Birth of Christianity in the Americas. After a decade of research, her book was released in 2021, the second full year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I tried to keep my focus very much on the 16th century,” Hughes said. “Not try to solve all of our problems in the present, [but to] tell a rigorous, careful story about the past.”

The book has been recognized by the industry publication Publishers Weekly as among the best religion titles of last year. “The story seems to resonate,” she said.

In 1576, when this epidemic struck, church bells initially tolled for each person who died of the mysterious plague, but eventually, the death count rose so high that the bells stopped ringing.

“I got to the archives and realized there was so much I needed to understand about this one [epidemic],” Hughes said, adding that church officials of the era called the outbreak the “most devastating of the 16th century.”

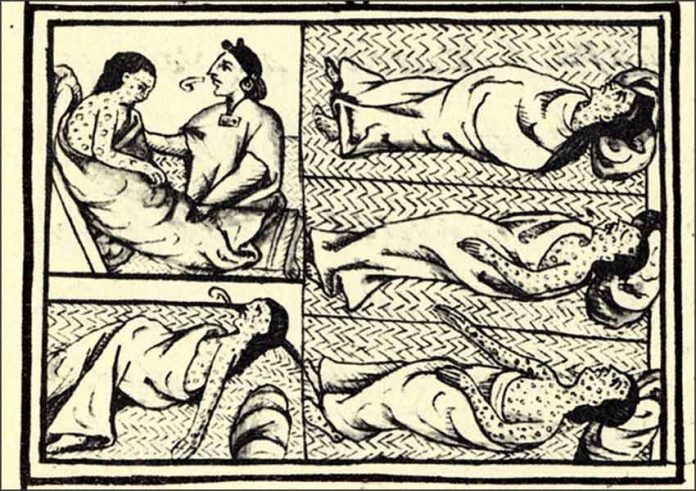

By 1576, the country had already been reeling from multiple infectious diseases that had accompanied the Europeans, most notably the smallpox epidemic spread by Hernán Cortés’ messengers to Tenochtitlán even before the conquistador reached the Aztec capital. In the decades following the conquest, epidemics had periodically ravaged indigenous populations, who created a term – cocoliztli – to name any unknown disease that was killing so many of them in such painful ways, such as bleeding to death. One such cocoliztli epidemic — one previous to the plague that’s the subject of Hughes’ book — occurred in 1545; she describes it as the most devastating in terms of numbers.

“[The 1576 epidemic] reduced an already terribly devastated population,” she said.

Citing scientific research into the 1545 epidemic that attributed that outbreak to salmonella, Hughes suggests but cannot confirm that salmonella was also the source in 1576. But whatever it was, the late-16th-century cocoliztli epidemic provoked a reckoning within the Catholic Church in Mexico.

“After a century of demographic catastrophe, the church was in crisis,” Hughes said. “For many Spanish missionaries, especially those who were part of the first generation of missionaries, in the midst of this epidemic, they felt the church did not have a future in Mexico.”

“The church still had financial resources, its hierarchy, its priests. But the hoped-for vision of a utopian missionary church seemed no longer possible to many Spanish missionaries,” she added. “There was only a very compromised version that remained … [of the] initial hoped-for Christian evangelization of the continent, hemisphere, colony.”

The epidemic led to very different reactions from Catholic leaders in Mexico, and from the indigenous populations they sought to evangelize, she said.

“There’s the presence of two competing versions of what Christianity was going to be,” she explained. “Whether it would be indigenous-led … or led by Spanish priests, whether it would be a church composed of Spanish settlers or one that would be encompassing of indigenous people and their cultural practices, anchored in indigenous senses of the sacred.

“In our current crisis … like in past epidemic crises … you can see competing social visions come into sharp relief. Competing desires for the future, competing ideas on how we might move forward, are more clearly drawn.”

The debate in Mexico in the late 16th century addressed the fate of the pueblos de indios or reducciones — settlements of indigenous people relocated by Spanish colonizers — in a landscape depopulated by disease.

“The archbishop of Mexico at the time strategized to consolidate the remaining indigenous populations into reducción. Some settled areas were to be repopulated with Spaniards. His was a highly compromised vision of a church led by bishops, organized into dioceses, dispossessing indigenous people.”

“[The bishops’] vision was the church of the dead,” she said, citing a phrase incorporated into the title of her book. “A vision of a sort of church without indigenous people.”

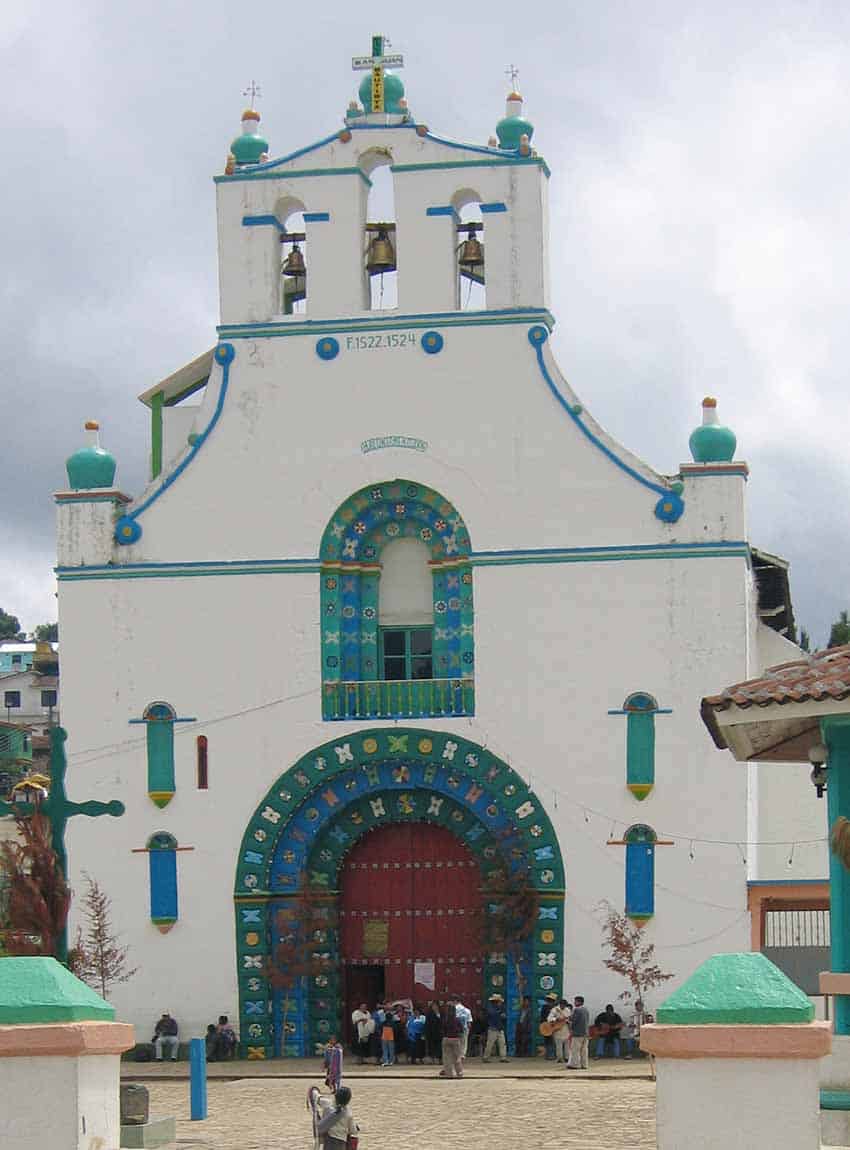

In contrast, she said, indigenous voices she encountered in the archives wanted to be very much present in determining the structure of the Catholic Church in each pueblo de indios.

“They said, ‘We’re going to be in charge; the church is under our care and our leadership.’”

The book describes Mexico’s indigenous people as enduring numerous injustices during this epidemic. Priests who initially tried to give medical help to cocoliztli victims grew disheartened and dropped their efforts after several months.

“The Aubin Codex, an important Náhuatl source I draw on, uses words that suggest abandonment,” Hughes said. “There’s a sense that their community has been abandoned by the church, forgotten about by the pastors they understood were there to care for them. It is a painful record. The church’s efforts did not cease altogether, but there was a notable retreat or withdrawal, a cooling.”

Despite such disappointments, Hughes finds a great deal of indigenous interest in Catholicism itself that survived the epidemic — but it was not a Catholicism on the colonizers’ terms.

“In the historical sources, I see these pueblos as understanding themselves to be Christian and very profoundly Catholic,” she said. “But for them to be Catholic was not the same, necessarily, as submitting to Spanish authority and rule.”

Rather, Hughes said, indigenous people wanted to “develop the religion on their own terms, under the protection of their community elders and leaders, whose authority was often more important than that of a possibly difficult Spanish priest.”

Having previously researched how indigenous people incorporated Catholicism into their ritual and domestic practices, such as altars and images in their homes, Hughes was surprised to find that this also happened in their vision for the organization of the church.

“These communities often saw themselves as better Christians and Catholics than the friars themselves; they discerned or decided what was sacred and holy in the religion,” she said.

Sometimes this included rejecting “some dimensions of Christianity [that] they found not particularly holy … not particularly sacred.”

It’s a legacy that continues into the present.

“In the end, I see much of Mexican Catholicism today as the powerful patrimony of the pueblos de indios and their intense work to shape and maintain the Christian religion as they determined,” Hughes said.

Studying this long 1576 outbreak has made her wonder how long the current coronavirus pandemic will last.

“I often think about it now, being in COVID, especially given recent news about the [latest] variant, the sense that it’s a surging crisis,” she said. “Over five years [from 1576 to 1581], they also had these kinds of surges. There would come a moment of relative calm and then another devastating surge, something like we are experiencing in this pandemic.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.