When Mexican diver Joaquín Capilla Pérez headed into his final Olympics at Melbourne, Australia, in 1956, one thing was missing from a dazzling resume: a gold medal.

He closed that year with a splash, placing first. He ended his Olympic career with one gold, one silver and two bronze medals over three Summer Games.

With four medals overall, he remains Mexico’s most decorated Olympic medalist.

The long history of Mexican Olympic achievement includes a diverse medley of sports, from diving to equestrianism to boxing. There are some complicated moments, such as Mexico City’s experience hosting the 1968 Summer Games, in which Black American athletes participated in a notable social protest and student demonstrators died in an infamous massacre at Tlatelolco.

More recently, the men’s soccer team won a gold medal at London in 2012 and taekwondo practitioner María Espinoza placed second on the all-time Mexican medals list, with three, while race-walkers have accumulated 10 medals over the years, the most Mexican medals in a track and field category.

In Tokyo this year, Luis Álvarez and Alejandra Valencia won bronze in mixed-team archery, while in diving, the tradition of excellence continues: divers Gabriela Agúndez García and Alejandra Orozco Loza won bronze in the women’s synchronized 10-meter platform.

“I think Mexico has an interesting history generally in the Olympics,” said William Beezley, a professor at the University of Arizona. “Not high numbers of gold medals, but interesting stories, at least.”

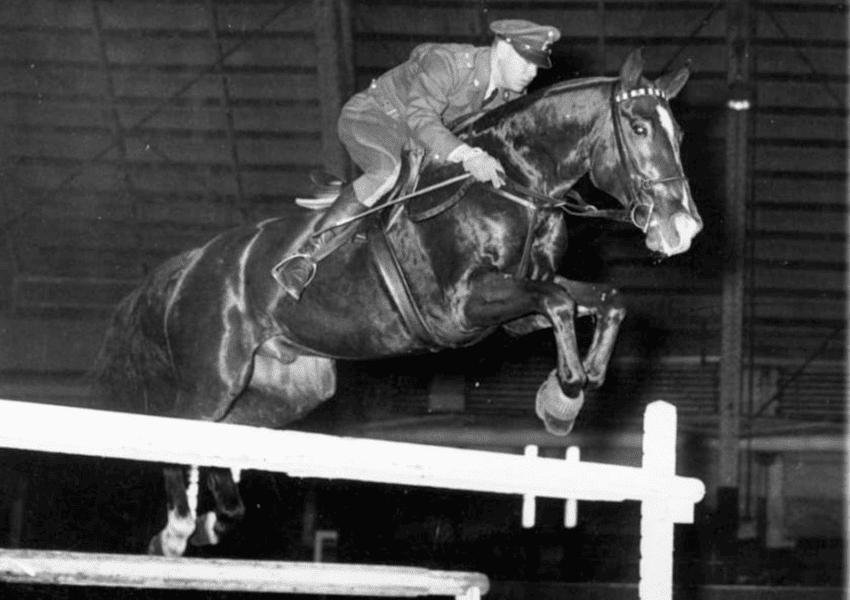

Mexican Olympic achievements began in Paris in 1900 with a bronze in polo.

“Mexico has a long history of sports related to horses,” said Zacatecas-born scholar José Alamillo, a professor at California State University-Channel Islands. “It goes back to the charro [cowboy] and the charreria [equestrianism].”

Mexico fielded its first official Olympic team for the 1924 Paris Summer Games. The National Olympic Committee looked to indigenous running traditions among the Tarahumara community, as a route to success in 1924 and 1928 (the Summer Olympics in Amsterdam).

Although the Tarahumara athletes were veteran long-distance runners, they did not win Olympic marathon medals.

“The story goes that the distance was too short,” Beezley said. “These guys were used to running 50, 60 miles. Just doing a marathon distance was only half what they were used to. They were just getting warmed up, getting ready to go. It’s just a story. The real story is, who knows?”

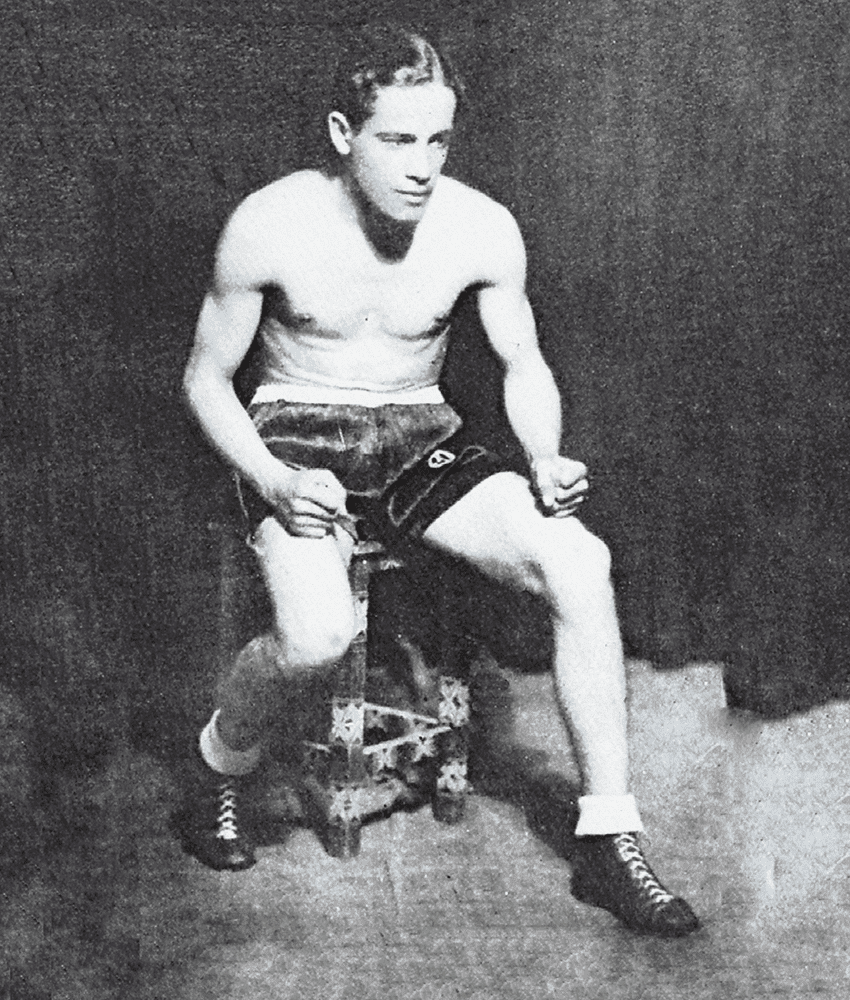

In the next decade, flyweight boxer Francisco Cabañas won one of Mexico’s first two individual Olympic medals — a silver at the 1932 Summer Games in Los Angeles. Gustavo Huet Bobadilla also won a silver medal that year for shooting in the small-bore rifle, prone, 50 meters competition.

“Boxing [in Mexico] starts to take off in the late 1800s during the Porfiriato,” said Stephen Allen, a professor at California State University-Bakersfield and the author of A History of Boxing in Mexico: Masculinity, Modernity, and Nationalism. “There is a lot of incorporation of foreign sports from the U.S. and Europe. The Porfiriato pushed the elites to want to do the same activities as Europeans and Americans.”

Ironically, Allen noted, boxing was eventually banned. The working class in Mexico wasn’t allowed to participate for fear that the sport “would teach the working class how to fight,” he said. That did not change until the 1900s.

In the Olympics, “Mexico has been represented well by boxers,” Alamillo said. “[Cabañas] stood out because boxing is huge in terms of Mexican sports.”

Outside the arena, Mexican athletes faced another foe: racism.

“You definitely see a lot of Mexican stereotypes at the Olympics dating back to 1932,” Alamillo said. “Mexican athletes would be represented in sports journalism, often stereotyped, in many ways … very much a caricature of Mexico, stereotypically ‘hot-tempered,’ very much similar to a lot of racial stereotypes in Hollywood regarding Mexicans.”

A decade later, an inspiring friendship blossomed between two rivals who each overcame racial prejudice: Mexican diver Capilla and United States competitor Sammy Lee, an Asian-American.

“You can definitely see both Sammy Lee and Joaquín facing these things, especially how they were represented in sports media,” Alamillo said. “There were a lot of similarities.”

Although Capilla enjoyed many triumphs, he later struggled with personal issues. “[Capilla] ended up in poverty. Things went bad for him,” Beezley said.

Another Mexican Olympian with success on the podium but difficulties later in life was Humberto Mariles, a three-time equestrian medalist at the 1948 Summer Games in London — including two gold medals, the only time a Mexican has topped the podium multiple times.

Mariles, later jailed for murder, “was a strange guy, is all I can say,” Beezley said.

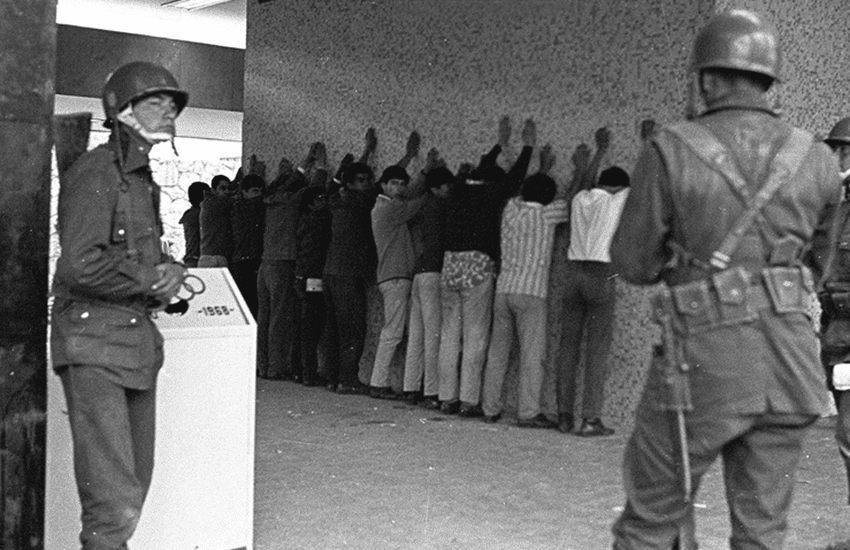

Scholars had much more to say about Mexico City’s experience hosting the 1968 Summer Games.

“For Mexico’s establishment, the 1968 Olympics, and the 1970 World Cup, were supposed to be a moment when the world watched as a ‘new’ and ‘progressive’ Mexico emerged on the global stage — with a thriving economy, an artistic flair and a new level of technological sophistication,” said Mark Dyreson, the director of research and educational programs for the Penn State Center for the Study of Sports in Society.

“Clearly, hosting the 1968 Olympics is head and shoulders the most important moment” in Mexican Olympic history, Dyreson said. “Mexico became the first nation in the Western Hemisphere outside the U.S. to host a Games — and the second nation after Japan in [1964] outside of Europe or its former British colonies — the U.S. and Australia — to host.”

Yet the Games ended up being remembered for off-the-field moments reflective of the era.

“The 1968 Olympics still have an important legacy in Olympic history,” Alamillo said. “I think there are a couple of reasons why. First, you have the African-American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos. They raised their gloves during that year’s national anthem [in the Black Power salute after winning gold and bronze, respectively, in the 200-meter dash]. “I think that protest still stands out today in thinking about the history of Black athletes making a statement.”

“The other reason is Tlatelolco, the massacre at Tlatelolco, [which] in many ways tainted the Games.”

In 1968, 10 days before the Olympics opened, the military shot unarmed student protesters gathered at the Plaza of Three Cultures in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco.

“Ultimately, Mexico could not escape the global forces that swept the world in the late 1960s and highlighted the endemic problems of racial discrimination, economic disparities, social conflicts and other maladies that impacted most nations,” Dyreson reflected.

“What was supposed to be Mexico’s coming-out party instead descended into the tragedy of the Tlatelolco massacre,” he said.

Nevertheless, Mexican athletes marked positive milestones that year: fencer María del Pilar Roldán became the country’s first female Olympic medalist when she won silver. Track and field competitor Enriqueta Basilio lit the Olympic flame, the first woman to do so.

At Sydney in 2000, 32 years later, weightlifter Soraya Jiménez became Mexico’s first female gold medal winner. Ana Guevara won a silver medal in 2004 in Athens.

At the 2016 Summer Games in Rio, taekwondo athlete María Espinoza captured her third Olympic medal to tie Mariles at second place for the most medals won by a Mexican.

Guevara, who Beezley called a role model, eventually was elected to Congress and served from 2012 to 2018, where she had to confront men who were “opposed to women athletes, to women being in politics,” he said.

In general, he added, Olympians here have “served as important role models in Mexican society for what’s possible, what can be accomplished.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.