“El Puente de Dios is a natural wonder you have to see. It’s a kind of tunnel with two huge arches, through which a river flows … It’s truly a marvel, but, unfortunately, getting there is one big chinga.”

This is what people in the know told me — some years ago — about one of western Mexico’s most unusual natural attractions. Such words might have discouraged the boldest of adventurers, but not my friend Chale, even though he was well over 70 years old at the time.

“I found the place on the topo map,” he told me. “It’s about 125 kilometers straight south of Lake Chapala, really in the middle of nowhere. Let’s go find it.”

Now if you look at a map of Jalisco, all you’ll see on its southernmost border is a big empty space, but Chale assured me there’s a little town there with the nearly unpronounceable name of Ahuijullo (ah-wee-HOO-yo). “That’s where we’re going,” said Chale, “and we’d better bring along enough food to last us five days, just in case.”

Unforeseen circumstances resulted in the postponement of our trip, but this did not stop Chale from driving 606 kilometers (round trip) of curvy roads “just for a preliminary look.” He came back with good news: “They’ve opened an iron mine near Ahuijullo and built a big wide road to it. We can easily get there from Michoacán.”

So, off I went the following week with Chale and another willing hiker nicknamed Sobina. Sure enough, we found a graded road, wider than any autopista, leading from Tepalcátepec, Michoacán, to Ahuijullo, Jalisco. The only problem was that we had to share this road with 92 huge trucks which, in those days, were carrying iron ore 24-7 from the Piedra Imán Mine: trucks which raised enough dust to choke all of us to death if we hadn’t had air conditioning.

Our car was white when we left Tepalcátepec and brown by the time we reached the home of one Hernán Lomelí, whom Chale had contracted as a guide.

“You need a place to camp?” said Hernán. “You can share my pasture with the cows.” And so we did, only to discover at 3:00 a.m. that we were also sharing it with several thousand local roosters which seemed dead set on getting us up before dawn.

The next day we asked how long it would take us to walk to the Puente de Dios. “About two hours,” everybody told us, “está retirado [It’s pretty far away].” Well now I know that in rural Mexico the word retirado means “double whatever walking time they tell you.”

Our hike took us up and down golden hills and all along a bubbling stream which comes straight out of God’s Bridge and which we must have crossed 500 times, hopping from boulder to boulder. Along the way we saw a big black snake almost two meters long, papelillo trees with paper-like bark, ceibas covered with fluffy cotton balls and bonete trees full of fruits shaped like bombs, while overhead flew a flock of long-tailed magpies, which followed us for at least an hour, cavorting like lunatics.

Unlike us, our guide and his buddy were riding on horseback. Eventually they must have gotten tired of waiting for us at every crossing of the river, for suddenly they vanished. “They may be lost,” pronounced Chale, utterly calm, “but we are not. As long as we follow the river, we’ll reach the Puente de Dios.”

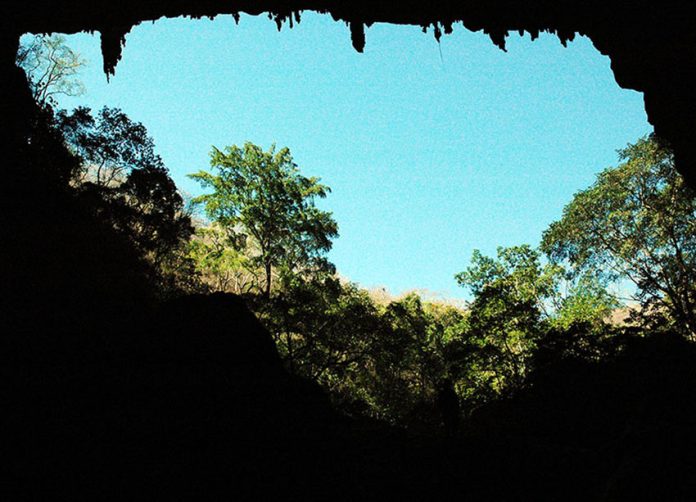

After a total of four hours of walking, we found our guides heating tortillas in front of the huge arch of a cave entrance. Sobina threw himself on the ground and declared he was never moving again. Chale and I, however, had just enough energy left to enter the cave, which has two spectacular arches a few hundred meters apart.

The river runs right through the cave and its high, cathedral-like roof — which sports a third impressive “skylight” entrance — is dripping with stalactites, curtains and flowstone.

Several beautifully decorated natural balconies were visible and our guides assured us it was possible to reach these lofty places because local people had already climbed up there in hopes of finding a wonderful treasure which supposedly had been hidden here … and in just about every other cave we’ve ever heard of in Mexico.

Unfortunately, visitors have succeeded in removing many of the stalactites by shooting them to smithereens, but in spite of this, the Puente de Dios is still an awesome sight and also of historic interest because a local bishop is said to have lived in it during the time of the Cristeros and the ghost of a famous brigand is supposed to haunt the place to this very day.

No doubt both of them enjoyed drinking the cold, unpolluted, river water as much as we did. Our canteens, in fact, had run dry long before we reached the cave and if that river water had not been safe to drink, we would certainly have known it. Local people, by the way, are proud of this place and organize a pilgrimage to the cave every May 1 and I bet even the abuelitas (grandmothers) get there faster than we did.

Well, the hike to God’s Bridge was one of the toughest of my life so I never included it among the sites listed in my Outdoors in Western Mexico books. Recently, however, I was alerted to the fact that adventurous souls in the town of Tecalitlán, Jalisco (a two-hour drive whether from Guadalajara or Ajijic), have been organizing visits to God’s Bridge utilizing all-terrain vehicles which get you there via dusty brechas (dirt roads) overhanging steep precipices.

[soliloquy id="113030"]

“You actually hiked all day long to visit El Puente de Dios?” exclaimed Ismael Orta of Tecalitlán Turismo. “Well, now it’s a walk of 20 minutes, maximum.”

So, if you love racing up and down steep slopes in a motorcycle or ATV, call Ismael and he can arrange the adventure of a lifetime for you, culminating in a stroll through God’s Bridge — if you survive the off-road journey, of course (just kidding). In case you are the owner of your own four-wheel-drive vehicle, you could choose whether to meet Ismael and friends at Tecalitlán (100 kilometers from the bridge) or perhaps at pretty little Ahuijullo, 14 kilometers from the Puente de Dios. Just ask Google Maps to take you there.

Maybe if you spend the night in Ahuijullo, you will even figure out how to pronounce it.

• For more information, call Ismael Orta at 331 436 2441. (Yes, you can use Whatsapp.)

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.