March is Women’s History Month, so let’s begin with what may be the only group of women from Mexico’s past that foreigners know, at least from photographs.

The term Adelitas (“little Adeles”) is used in Mexico today to refer to women who participated in the Mexican Revolution, battling government forces.

To understand their story, it is important to understand just what the Revolution was. It began in 1910 as several uncoordinated revolts against the decades-long rule of President Porfirio Díaz. Díaz was deposed rather quickly, but the shooting continued for the rest of the decade as these same factions fought each other for power.

By 1920, Álvaro Obregón was president, the last of the major rebel leaders to survive. His government would consolidate as the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or Institutional Revolutionary Party, and rule Mexico until 2000.

As in most wars, women participated, but they and their stories have been pushed into the background, both because of machismo and because of the real desire by men to keep their families out of harm’s way. Women fed soldiers at camps and often took care of each others’ children and took over male jobs such as farming. Women picked up guns as well, either to defend themselves while their men were off fighting somewhere else or because they were motivated to join one of the factions.

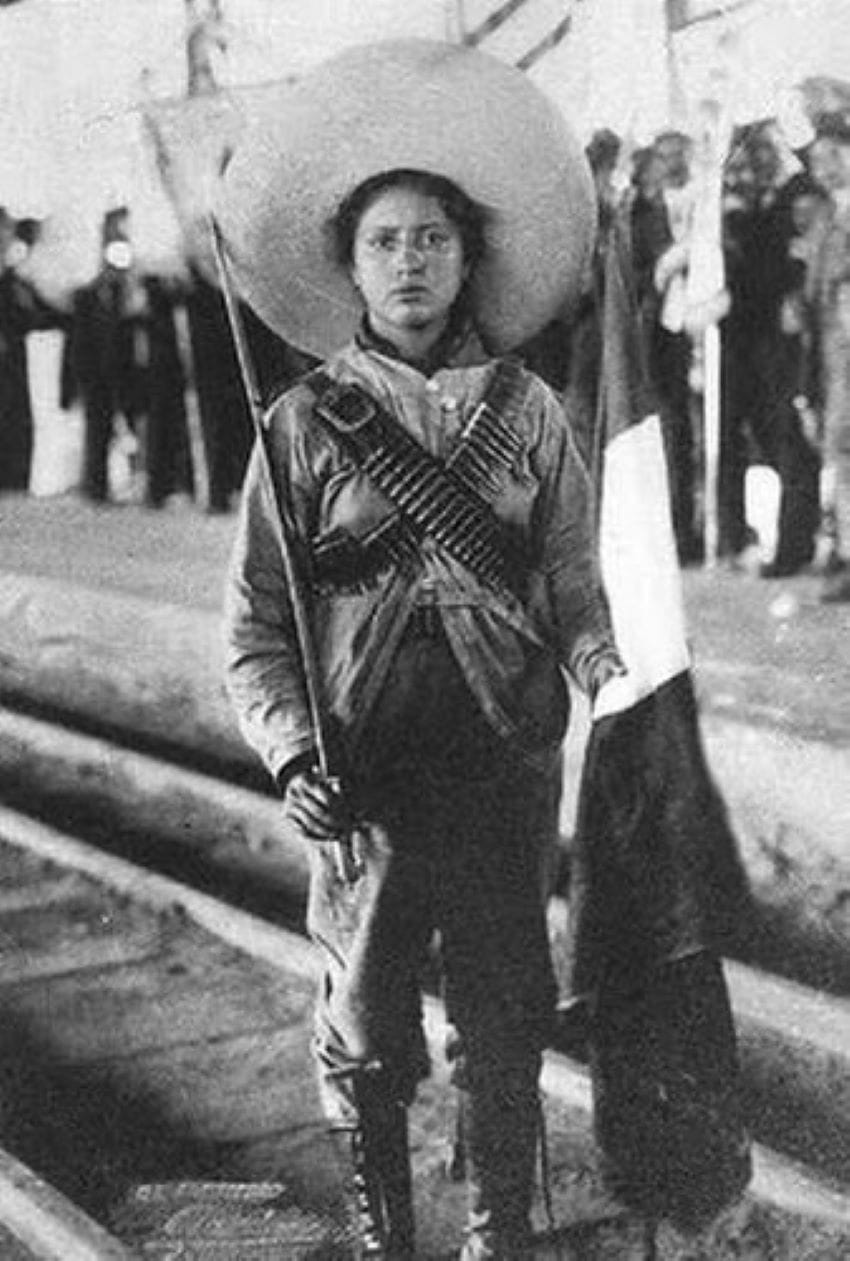

The classic Adelita is depicted with humble dress, rebozo (a long shawl), bandolier and rifle. It’s an image made famous by Mexican photographer Agustín Víctor Casasola and others who spent years documenting the fighting for the national and international press. The image has some basis in reality as Adelitas were almost always poor and in rural areas, where fighting was heavy.

Their roles during the Revolution are worth documenting, but also interesting is how they have been portrayed in the century since the fighting ended.

The fame of the Adelitas is initially attributed to a song, a type of ballad called a corrido. The origins of La Adelita are in dispute, but it became popular during the war.

The corrido developed various regional versions, each claiming to be the original and most authentic. However, Adelitas in these corridos are not portrayed as some kind of Amazon warrior. Instead, she is not much more than a sex object, a reason for men to fight.

There are a number of claims that the original Adelita was a military nurse by the name of Adela Velardo Pérez, who ran away from home at the age of 14 to join the Cruz Blanca (White Cross), an organization that tended to wounded soldiers. In 1948, Velardo told the newspaper Excélsior that the famous “Adelita” corrido had been composed by Sergeant Antonio del Río, who was in love with her but died before the two could marry.

According to historian Martha Eva Rocha Islas in the book Los rostros de la rebeldía (The Faces of the Rebellion), the term Adelitas originally referred to the nurses with revolutionary forces, an assertion that supports Velardo’s claim.

Velardo’s role was recognized with a veteran’s pension in 1963 and acceptance into the Mexican Legion of Honor. She died in 1971 in Texas and was buried in the town of Del Río.

For decades, Mexican history books focused almost entirely on the men who participated. During the war itself, Adelitas were denigrated as marimachas (tomboys, to use a nice translation), not respectable women. The Mexican writer Carlos Monsiváis once stated, “The Revolution was a man’s business, and women were the decorative backdrop …”

If women were mentioned, their role was subordinate, with histories explaining their presence as being a case of dire need. In popular culture, especially the movies of the 1940s and 1950s, Adelitas as combatants were depicted distant from the male heroes and sometimes as “bad” women.

Later corridos continued the tradition of depicting women during the Revolution as examples of beauty, bravery and passivity, generally as a romantic interest not a warrior, and certainly not equal to men.

In more recent decades, Adelitas have been reevaluated. Their role is more likely to be depicted as a kind of cabrona (bitch) in the sense of someone who cannot be dominated, someone who is willing and able to abandon her domestic roles to fight for the cause — and not waiting for the permission of men to do so.

Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska wrote in Las Soldaderas (The Women Soldiers), “Without them, there was no Mexican Revolution. They kept the land alive and fertile.”

Initial academic research into the Adelitas’ lives began in countries like the United States, but Mexican academics are catching up.

Because the women were almost always from the disadvantaged classes, few of their names are known, with some exceptions.

One is Hermila Galindo, who was involved in anti-Díaz politics early with an important role in the Venustiano Carranza army. She is also considered to be an early feminist in Mexico.

Carmen Serdán became prominent for her ability to procure supplies for troops. Ángela Jiménez became an expert in explosives. Amelia Robles became noted for her ability with a pistol, even earning the rank of coronel (colonel).

Petra Herrera contributed to Pancho Villa’s army as an organizer and leader. At the Battle of Torreón in 1914, she caused the lights of the city to black out so that Villa’s army could enter, but Villa never recognized her contribution. Their relationship soured, causing Herrera to split off and form her own all-women army of over 1,000.

It is neither fair nor accurate to depict all Adelitas as either femme fatales, fallen women or Amazon warriors. Like their male contemporaries, most were doing the best they could during a bloody and chaotic civil war.

Mexico is changing and, at least, any pejorative meaning Adelita had is long gone. What remains to be seen is if depictions of these women can evolve past simplistic archetypes.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 17 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture. She publishes a blog called Creative Hands of Mexico and her first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published last year. Her culture blog appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.